The Thing (1982): Part 2 of 2

Alternate casting, holy hiatus, testing madness, feel bad summer

Get caught up. Read The Thing (1982): Part 1 of 2 here.

In the month of October, Video Days is looking out for scaredy cats, counting down to All Hallows’ Eve with seven horror movies in ascending scariness.

THE THING (1982) was conceived as an ensemble, and to assemble a cast, Universal’s casting director Anita Dann cast a wide net. Any character might have been a lead, the actors perhaps credited alphabetically. To play the pilot MacReady, Jeff Bridges, Nick Nolte and Christopher Walken were considered, but were unavailable or passed without comment. Sam Shepard was interested, but never met with producers either. Tom Atkins, who’d been both a masculine and sympathetic presence in The Fog and Escape From New York, came in. Scott Glenn and Ed Harris took meetings, but quickly passed. Carpenter was explicit that the show required exterior shooting on a glacier and would not be comfortable. According to Stuart Cohen, Peter Coyote and Tim McIntire (who’d played Alan Freed in American Hot Wax) had reservations about appearing in a monster picture. Jack Thompson, who’d been featured prominently in the Australian film Breaker Morant (1980), flew to L.A. to meet and was a strong late contender. Carpenter had been consulting his friend and frequent leading man Kurt Russell about who to cast, and came around to offering him the role of MacReady, which Russell accepted.

For the role of the station manager Garry, Jerry Orbach was considered. Richard Mulligan wanted the role, and was also considered for Palmer, the backup pilot and sixties burnout. Mulligan, who’d steal Teachers (1984) from Nick Nolte, would’ve been great in either part, whether leaning dramatic or comedic, but Donald Moffat, who Russell had worked with on an episode of The New Land in 1974, was cast. For Blair, a biologist, Lancaster’s script had implied that his character was infected early, his vandalism of the camp a ruse to avoid suspicion of being the Thing. Carpenter considered offering the role to Donald Pleasence, but the actor was considered too well known to disappear for the length of time his character did. Wilford Brimley, whose screen debut in Absence of Malice (1981) hadn’t been released yet, received a strong endorsement from director Sydney Pollack. William Daniels was ideal for Dr. Copper and submitted by his agent. Brian Dennehy nearly won the role, but in a back and forth, Carpenter chose Richard Dysart. Rob Bottin lobbied for the part of Palmer. Too young to play the character as written, Bottin lacked acting experience and had plenty on his plate creating the makeup effects. Several standup comics–Charles Fleischer, Jay Leno, Garry Shandling–met for the part of Palmer. In the end, the best actor, David Clennon, was cast. Richard Masur was considered for the meteorologist Bennings, but the actor was intrigued by Clark, the dog handler. Masur, who sort of resembled a big but timid canine, was given the part.

The Thing commenced filming in August 1981 on soundstages at Universal Studios in Los Angeles. The start date had been moved up to avoid a SAG strike threatened for mid-October. Waiting for snow, shooting the research station exteriors in British Columbia couldn’t begin until December. This was a gift from the Muses that would make a huge impact on the overall quality of The Thing. The schedule gave Carpenter a six-week hiatus to view an assembly before resuming production in Canada. Upon viewing eight weeks of footage, he was despondent. The process of how characters were assimilated by the Thing seemed vague. Scenes were repetitive and dragged on. Amid the ensemble, the movie had no point of view. The first improvement Carpenter made was addition by subtraction. Superfluous character moments–MacReady spending time with a blowup doll, Childs cultivating a cannabis grow–were removed. Much of the bickering between the men was cut back. Carpenter realized the demise of Bennings (Peter Maloney)–stabbed by an unseen assailant, like a moment out of Halloween II (1981)--needed to be rethought, as would the death of Fuchs (Joel Polis), a young biologist, who in the assembly, was found impaled to a door by a shovel.

Over a weekend, John Carpenter wrote several new scenes to clarify how the Thing assimilated its victims, or fix the point-of-view problem by moving MacReady into the role of a classic if unlikely hero. Carpenter’s uncredited contributions as screenwriter were:

(1) Garry and Dr. Copper defer to MacReady on whether he wants to fly to the Norwegian camp.

(2) Blair studies a computer simulation which demonstrates how the alien organism invades its host’s cells and assimilates them. Once Blair runs a calculation on how much time the invader would need to assimilate the human race if it reaches a populated area, he retrieves a pistol from his desk. The simulation would be animated by Carpenter’s friend John Wash, who performed similar triage on Escape From New York, animating a title sequence clarifying how New York became the nation’s one maximum security prison.

(3) Fuchs speaks to MacReady in the SkiDozer to reveal that Blair has shut himself in his room and has written some alarming things about the alien organism in his notebooks.

(4) Bennings assimilated on camera–and in the second best sequence in the film–his unfinished doppelganger dashes into the show, to be burned by MacReady while the men watch in horror.

(5) Garry confronts MacReady, dumbfounded by what he just saw happen to Bennings. Donald Moffat would add a line revealing Garry’s friendship with Bennings.

(6) In another eerie moment, MacReady, his back to the camera, records a testament on cassette tape, further explaining how the Thing seems to assimilate its victims and its effect on the morale of the camp (“Nobody trusts anybody now.”)

(7) MacReady laying out to the men what they’re up against (“This thing doesn’t want to show itself. It wants to hide inside an imitation.”)

(8) The demise of Fuchs. Carpenter’s producer Larry Franco told the director he could reshoot the death scene any way he wanted, as long as he figured a way to do it in three hours.

(9) MacReady telling Garry, Childs and Nauls, “We’re not gettin’ out of here alive. But neither is that Thing.”

The scale of The Thing compelled Carpenter to accept help composing the music, which he’d tackled himself or with help from Alan Howarth since Dark Star. Jerry Goldsmith was unavailable. Alex North had ideas he was willing to discuss, but the only composer Carpenter trusted his film with was Ennio Morricone, who’d scored the Sergio Leone westerns. In December 1981, Morricone accepted a flight to Los Angeles to look at Carpenter’s assembly. He had some of the same concerns as Carpenter did, but agreed to work on the music in Rome. Carpenter later flew there, communicating through an interpreter, and using a piano to convey what he wanted in the music. “Fewer notes” was a common denominator. Due to the schedule they were working against, rather than spot score each scene with an orchestra, Morricone composed a series of suites, recording electronic elements in Rome, and traveling to L.A. to conduct portions with an orchestra. Carpenter then inserted cues where he saw fit. On another note, Universal licensed “Superstition” by Stevie Wonder for the initial theatrical prints only. When The Thing debuted on videocassette and cable television, “One Chain (Don’t Make No Prison)” by Santana, which Universal owned the publishing rights to, was temporarily substituted.

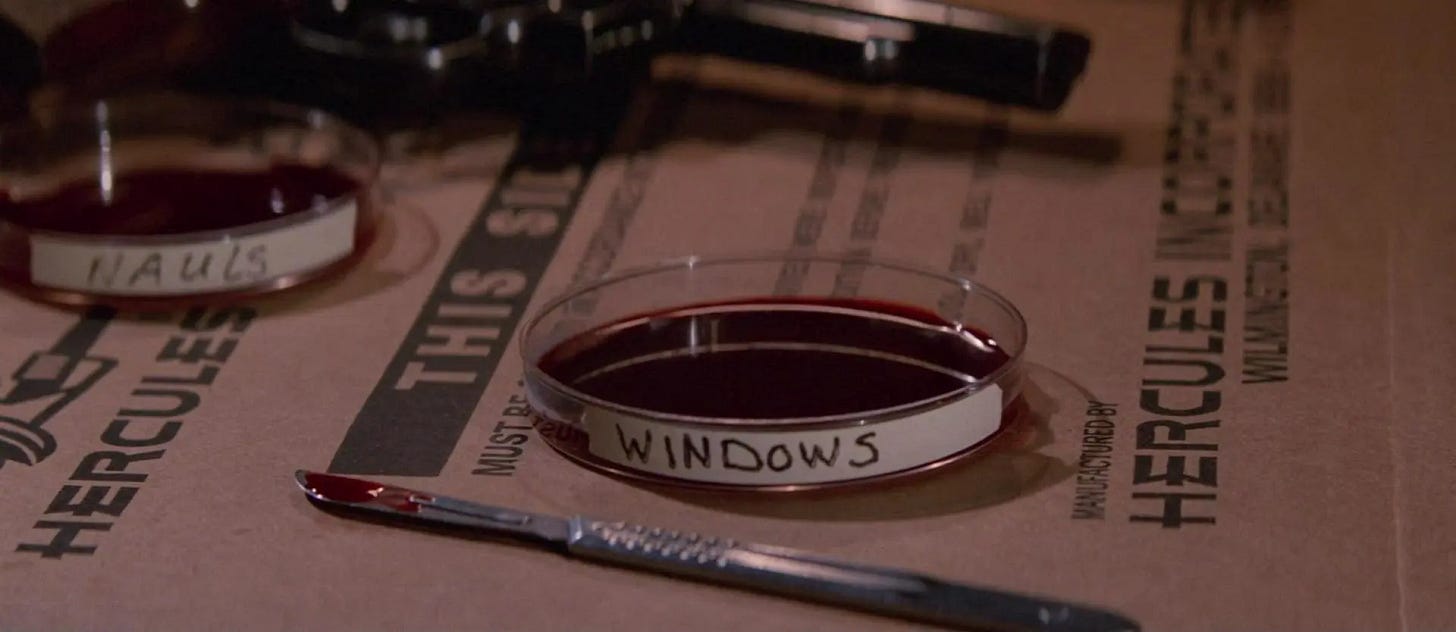

The Thing was put before a preview audience in late May 1982, at Red Rock Theaters in Las Vegas, after a Friday night screening of Conan the Barbarian. John Carpenter and Rob Bottin were in attendance. Universal executives were also arriving to get a look at the film for the first time. Robert Rehme, head of distribution, had confided to Stuart Cohen that the studio was counting on The Thing to be a hit. E.T. the Extra Terrestrial (1982) had yet to screen for a test audience, but looked soft, and Universal thought its appeal would be limited to children. What became evident was that The Thing had plenty of people to alienate too. Cohen recalled walkouts during the autopsy scene, with audience members at a test screening in Denver the following night following suit. Other than applause for the makeup effects–which greatly pleased Bottin–viewers mostly sat in uncomfortable silence. Convening at a conference room at Caesar’s Palace, the filmmakers shuffled through a few cards marked “excellent,” a larger number marked “good” and the majority marked “average.” Many of the “average” responses cited the amount of gore they thought they saw. The MPAA had blessed The Thing with an R-rating, but audiences were not digging the movie. Universal floated whether or not Carpenter was open to trimming the gore, but he demurred, and according to Stuart Cohen, the studio never brought it up again. Carpenter later mused, “You gotta take this stuff seriously, I feel, in order to make this movie something more than kind of a creaky monster movie. Basically what you’ve got in monster films, is if you have a guy in a suit, you end up there. You end up in some kind of technique, and I wanted to do a movie where you didn’t have that, where this was a real creature.”

One thing Carpenter was willing to bend on was confusion over the ending. Who won? Us, or the Thing? Who was the Thing? With the lab needing to start striking prints the following Tuesday in order to make a June 25 release date, Verna Fields spent most of the week using alternate takes to give the ending clarity. In this revised ending, Childs simply disappears and MacReady is left alone to ponder his fate. On Friday, two test screenings convened simultaneously at Universal Studios in Los Angeles, one with the original ending and one with the new. Ned Tanen, Universal production executive Helena Hacker, John Carpenter, David Foster, Stuart Cohen and Todd Ramsay were all there. By a margin of error, 3-4%, viewers favored the new ending, and the filmmakers made the decision to go with it. Taking the weekend to think this over, Hacker and Cohen agreed that a gentle landing betrayed everything that made The Thing powerful. Carpenter, communicating by telephone from North Carolina, where he was scouting locations for what he anticipated would be his next picture for Universal, an adaptation of Stephen King’s novel Firestarter, endorsed the original ending. A primal scream was added for viewers who needed some reassurance that an explosion did destroy the Thing. Maybe.

The Thing opened on June 25, 1982 on 840 screens in the U.S. Critics leaned negative, surprisingly, considering that a very adult, very graphic remake of an RKO horror film–Cat People–had been well-reviewed by some of those same critics in April. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert split. Siskel wished The Thing wasn’t as “ugly” as it was, but appraised the storytelling and subtext as well-made. He gave the film a backhanded recommendation, with a disclaimer that some viewers would be sickened by it. Ebert was not nearly as accommodating, faulting a lack of character development as well as implausibility, with the men failing to institute the buddy system for safety. Ebert labeled The Thing the most nauseating thing he’d seen on a movie screen. Siskel retorted, “I think it’s about how a society–this little group here–once the poison … they think there’s something going wrong, ‘You’re not in the group, you’re out.’ Just that line, ‘Move away to one side.’ It’s a very chilling thing. And I think if you read the movie in that way, the implausibilities at your level mean very little.” Universal had attached a trailer for The Thing to over 1,000 prints of E.T. when it opened June 11. Stuart Cohen recollected, “Our trailer was being seen by more people on that day than any other in motion picture history. I went down to the Cinerama Dome for that reason to see the trailer with the film, along with David Foster, there was no reaction whatsoever. This ultra-sold out crowd of grandmothers with their grandkids, no reaction at all. I had a feeling that we were in trouble and we were. There’s a toxic stew of reasons why I think the film failed, but the zeitgeist was a big part of it.”

On its opening weekend, The Thing faced the following lineup: E.T., Blade Runner, Firefox, Rocky III, Star Trek II, Annie, Poltergeist and Megaforce. It only managed to outperform the latter in ticket sales. Universal expanded the release to 910 screens for the Fourth of July weekend, but dropping half of those screens after three weekends in the market, The Thing disappeared from the top ten grossing films. Carpenter admitted to entertainment reporter Dale Pollock, “I’m puzzled. Mostly because I feel that I’ve made one of my best films, a very powerful, dramatic movie.” The poor reception of The Thing led to Universal cutting a proposed $27 million budget on Firestarter back to $15 million. Rather than make a bargain version, Carpenter took his pay-or-play salary and walked. Like Blade Runner, which Ridley Scott chose to tweak a couple of times after a disappointing theatrical release, it was on videocassette that The Thing was not only reappraised as a classic, but grew in stature to one of the most highly regarded science fiction films ever made. On October 27, 2023–retired from filmmaking and now touring the world with the backing of a small band to perform his film scores live–Carpenter visited The Late Show with Stephen Colbert, where Colbert gushed that The Thing was his “happy place” and might be his favorite movie.

Amid the ensemble of The Thing, an actor who’s often overlooked is Jed, a Vancouver Island wolf and Alaskan Malamute mix, playing the lone survivor of the Norwegian camp (Clint E. Rowe was the dog’s owner/ trainer). With everything going on both textually and subtextually in this tale of subzero apocalyptic horror, there’s Jed, giving a performance as terrific as any human in the cast, an animal able to convey he’s been through something terrible, and maybe knows more than he can communicate. The question of what it means to be human (or who goes there?) provokes much of our great science fiction, and that curiosity is embedded in The Thing, one of the best films of its class ever made. Rather than settle for being another horror or monster picture featuring strong visual elements, The Thing proceeds as a superior locked room mystery: a cast of characters are trapped by a storm, with one or more of them not who they appear to be. The screenplay by Bill Lancaster (and John Carpenter) improves on that old chestnut by Agatha Christie by refusing to unmask the killer, explain its motives or walk the viewer through how it conducted its crimes. We’re left to imagine that, and our answers are more disturbing. Who was infected first? Which character sabotaged the blood supply? In the end, who’s the Thing? And if you were absorbed by this alien, a perfect imitation, would you even know it? The climax demonstrates that its victims do know, yet Carpenter directs the actors like a shell game, with characters we learn weren’t infected wearing suspicious looks, while those who are the Thing often come across as the most “human.”

A prequel, also titled The Thing (2011), is only watchable in terms of how closely it mimics The Thing (1982) in ambiance and the game of guessing who’s who, with Mary Elizabeth Winstead a capable substitute for Kurt Russell as an action lead. It’s not a prequel as much as it’s a remake. One of the more extraordinary things Carpenter does, considering what a student of Howard Hawks he was (in Halloween, a TV that babysitter Laurie Strode is using to entertain her charges broadcasts The Thing From Another World) is to go his own way with his own film. Instead of Americans with resolute spirit rallying to victory against an existential threat, these men, living in an age of television, seem to know the game is rigged, even in Antarctica. Pessimism may have been what so turned off viewers in 1982, that and being poked in the ribs with autopsies or blood drawing that seemed unusually morbid. Budget cuts–the demise of one character is so obviously a mannequin being twirled around that it threatens to upset the cosmic horror in what is otherwise the best sequence in the film–produce a thriller that isn’t exactly streamlined. Rob Bottin’s makeup effects have stood the test of time, crackling with amazement at how anyone wrangled these creatures on camera, while the thinly dispersed score is a magnificent meeting between Ennio Morricone and John Carpenter, two film composers who defined their eras. If The Thing were a cologne, it would be labeled Pulsating Doom.

Video rental category: Horror

Special interest: Staff Picks

Thanks to Stuart Cohen and his blog, The Original Fan for exhaustively detailing the production history of The Thing (1982).