Year of the Dragon

Cowboy cop takes on Chinatown in ornate but contrived spectacle

Video Days orders readers to surrender their badge and gun and while suspended for the month of May, return to ten films trafficking in law and order.

YEAR OF THE DRAGON (1985) is blunt force trauma not to the body, but the spirit. Scenes proceed as if both ends had been clipped off, throwing us into the thick of activity, little of which is justified by a story this elementary: an NYPD captain takes down the Chinese American tongs running heroin, extortion and gambling in Chinatown. It’s a public service announcement that would’ve won over the Moral Majority in the mid-’80s, a visually splendid piece of propaganda, but a bucketful of xenophobia all the same.

Robert Daley traveled the globe as a foreign correspondent for the New York Times from 1959-1964. He worked in eighteen countries before the bewilderment of being an alien wore on him. In 1971, he accepted a job as one of seven NYPD deputy commissioners, his expertise in public relations serving the people of New York. Daley had always wanted to be a novelist, starting one at the age of twelve and completing one ten years later that went unpublished. During his year with the NYPD, Daley absorbed everything he could about police work. Two of his first three books were non-fiction exposés about cops–Target Blue published in 1973 and Prince of the City in 1978–with his first novel, To Kill a Cop, published in 1976. Year of the Dragon hit bookshelves in 1981. It depicted the efforts of Captain Arthur Powers of the NYPD to take down gangster Jimmy Koy, a corrupt cop in Hong Kong who comes to America to take control of the Chinese underworld in New York and San Francisco. Daley had interviewed four Chinese American cops and various other policemen, as well as traveled to Hong Kong for research.

Producer Dino De Laurentiis wanted to make a contemporary movie about the Chinese underworld. He’d commissioned one of the script doctors on his payroll, George Gallo, to pen an original script, with Gallo taking his orders literally and titling it Slaughter In Chinatown. When De Laurentiis had the opportunity to option Robert Daley’s novel, he chose to develop Year of the Dragon as his Chinatown picture instead. To direct, he courted Michael Cimino, the prolific and some thought genius of commercials whose three films as director–Thunderbolt and Lightfoot (1974), The Deer Hunter (1978, for which Cimino won two Academy Awards, for Best Picture and Best Director) and Heaven’s Gate (1980)--were received with varying degrees of love and hate, though few questioned Cimino’s abilities as a visualist. After the massive failure of his lavish western, Cimino was retained to direct Footloose (1984) before his desire to cut most of the music from the musical led to a parting of ways with Paramount Pictures. Cimino spent less time if not effort stepping in to possibly direct The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984) for MGM/UA, Eric Roberts and Mickey Rourke already cast, before Cimino bowed out, dubious he could make the film he wanted on the time table mandated. When Dino De Laurentiis Corporation, which had bankrolled The Dead Zone (1983), Firestarter (1984), Conan the Destroyer (1984) and Dune (1984) at considerable expense and cut the ribbon on a production facility in North Carolina, offered Cimino a job, albeit one without the privilege of final cut, he said yes.

Cimino phoned Academy Award winning screenwriter Oliver Stone and summoned him to New York. The director described the material they would adapt as a hybrid of Dirty Harry (1971) and The French Connection (1971) set in Chinatown, and wanted to begin his departure from Robert Daley’s novel by focusing on a vigilante cop on a rampage, not unlike Tony Montana in Stone’s script for Scarface (1983), which Cimino was an admirer of. Stone had not been an admirer of the direction Dino De Laurentiis had taken his screenplay for Conan the Barbarian (1982) after the producer bought out Stone and producing partner Edward R. Pressman and took control of the Robert E. Howard character. Cimino proposed to De Laurentiis that Stone would accept half the writing fee he’d earned on Scarface–a bargain at $200,000–to co-write Year of the Dragon if De Laurentiis agreed to put up $7 million in financing for Platoon, Stone’s account of serving on an infantry unit in South Vietnam, with Cimino producing and Stone directing. After discussions at Cimino’s office in Union Square, Stone wrote Year of the Dragon alone at his apartment in uptown Manhattan, or a cottage on Sagaponack (the WGA would award writing credit to Michael Cimino & Oliver Stone, based on a novel by Robert Daley).

Stone had spent significant time in Los Angeles working on an unproduced screenplay about the hunt for the Hillside Strangler. To assist in his research, filmmaker Floyd Mutrux had put Stone in contact with two LAPD homicide detectives who’d worked the case, and those investigators had introduced Stone to Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department detective Stanley White, a Marine Corps veteran in Vietnam who, ironically, would consult with George Gallo on the script for what became Bad Boys (1995) and gave Gallo the idea to write Midnight Run (1988). Stone not only modeled much of the NYPD crusader in Year of the Dragon on White, writing him as a Vietnam vet, but renamed the character “Stanley White” as tribute. What Stone didn’t know about was Chinatown or its criminal underworld. A New York production manager named Alex Ho (who as A. Kitman Ho would produce seven films Stone directed, up to Heaven & Earth in 1993), arranged meetings with any civic authority in Chinatown he could find. Stone recalled banquets in which he was well fed but no one was willing to talk about drug smuggling, the opposite of what Stone had encountered researching Scarface in South Florida, where everyone knew who the drug runners were and how they operated. A Chinese American operation that had been run out of New York by other gangsters agreed to meet with Stone and Ho in Atlantic City and provided some background.

Mickey Rourke, who’d appeared in Heaven’s Gate and been featured among the ensembles of Diner (1982) and Rumble Fish (1983), was cast as Stanley White, with John Lone as his adversary (renamed Joey Tai), model Ariane Koizumi (billed as “Ariane”) making her film debut as an action news reporter who White becomes enamored with, Caroline Kava as White’s estranged wife and Raymond J. Barry as White’s confidant among the NYPD brass. [Stone would cast Kava and Barry as the parents of Ron Kovic in Born on the Fourth of July (1989), though Dino De Laurentiis had not helped Stone establish himself as a director, reneging on his agreement to produce Platoon, the screenplay to which Stone had to file a lawsuit against De Laurentiis to get the rights back to and direct in 1986, with John Daly of Hemdale Film Corporation financing the picture.] On a publicized budget of $24 million, Year of the Dragon commenced filming in October 1984 in Victoria, British Columbia, where Parliament Building stood in for the NYPD police commissioner’s office and the catacombs beneath the Empress Hotel were used to stage the mung bean factory scene. Two weeks of filming in Vancouver was necessary to stage scenes in the city’s Chinatown that couldn’t be spoofed on a studio backlot.

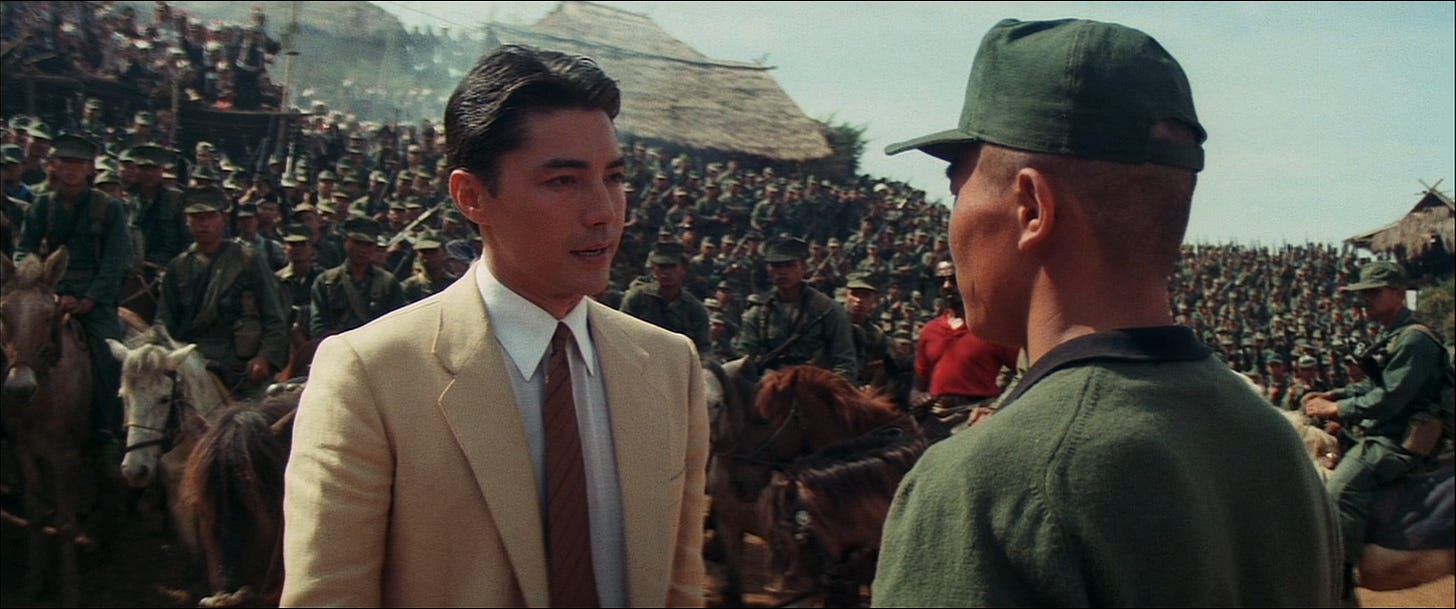

Location shooting in New York was centered around a 3.200-square-foot space on the top floor of a factory in Brooklyn which became the loft apartment for the reporter, Tracy Tzu. Cimino prized the location for its celestial views of the Brooklyn, Manhattan and Williamsburg Bridges, and the New York skyline, including the World Trade Center and Empire State Building. Cimino commissioned the Manhattan-based interior design firm of Lembo-Bohn Design to build the apartment. Six weeks of filming took place at North Carolina Film Corporation Studios in Wilmington, where a 480-foot replica of Mott Street, the unofficial Main Street in New York’s Chinatown, was built at a reported cost of $1.2 million, Cimino taking pride in its detail down to the grade on the sidewalks, something flat “New York Streets” built in Hollywood over the decades had not given attention to. The scenes in which Joey Tai visits the Golden Triangle were shot with John Lone and a significant cast of extras in the vicinity of Bangkok, Thailand. Year of the Dragon would open in August 1985 in 982 theaters in the U.S. Those most excited about it were a number of small but vocal protestors who took offense at the film’s depictions of minorities, particularly Chinese Americans. Twenty to thirty picketers staged protests outside theaters in New York, Los Angeles, Washington D.C. and Bellevue, Washington.

The protests drew the support of Boston Mayor Raymond Flynn, as well as Robert Daley, who condemned the film based on his novel for its ethnic depictions. At the time, Stone defended the accuracy of his script, relegating the protests to “organized Chinese groups” and those who didn’t know anything about Chinatown. Looking back on Year of the Dragon from the 21st century, Stone would admit that the racist rants that pepper White’s dialogue came off as flat, carried through without the irony they needed. (Not long after the film’s release, Cimino would refer to Stone as being a better writer than he was a director). Their film was treated coolly by critics and audiences. Though Roger Ebert gave it three stars in the Chicago Sun-Times, admitting the film was structurally a mess but entertaining, Janet Maslin of the New York Times found it “a busy and elaborate film that manages to be inordinately messy.” Commercially, Year of the Dragon didn’t make a dent against Back to the Future, the #1 film in the country for twelve of its first fifteen weekends, or prove as popular as the Michael J. Fox fantasy released on its coattails, Teen Wolf. Distributed by MGM/UA, it was chalked up by the press as another misfire in the studio’s arrangement with De Laurentiis, with Cat’s Eye (1985) and Red Sonja (1985) wringing nearly all that was left from Stephen King material or Robert E. Howard characters. It did spend five weekends atop the top ten grossing films before dropping off.

Year of the Dragon does have a point of view, at least. Cimino and Stone want us to know that Chinese Americans are the biggest importers of heroin in the U.S. and that the insulated nature of their communities have kept their criminal activities hidden for generations. But so what? Politicians painting their opponents as soft on crime want us to believe that drugs are the disgrace of a nation, but it’s unclear why Stanley White thinks that. His character has no stake in bringing law and order to Chinatown. We’re told that he’s a Marine Corps vet and a decorated cop–the most decorated cop in the city!--but neither of those jibe with his yahoo posturing. Cimino and Stone are just mimicking the obsessive methods of Popeye Doyle in The French Connection, as if White is a movie cop first, a complicated man second. While Mickey Rourke comes in just under the wire agewise for his character to be plausible as a Vietnam veteran, he’s replaying the excitable boy from The Pope of Greenwich Village, not a man who’s traveled to Southeast Asia, survived combat and would be more likely to employ violence as a last resort. His mission lacks a statement and his rants are phony.

In terms of set design and decoration, Year of the Dragon is a marvel. For reasons that might have been as simple as Dino De Laurentiis or Michael Cimino not trusting their director to make his follow-up to Heaven’s Gate on location, no movie shot mostly on a studio backlot had looked as dazzling since Blade Runner (1982), and before that, The Shining (1980). Wolf Kroeger, the production designer who built the world of Popeye (1980), headed the art department, and a handful of shots are worthy of freeze frame to study how they were pulled off, a parking lot in Wilmington standing in for Manhattan. After so much, grandeur isn’t enough. Cimino is so impressed with the apartment his designers built overlooking the Big Apple that White improbably moves in and starts holding bull sessions there. His character doesn’t work or play well with others, and White, for all his bluster, never figures out how to bust Joey Tai, both of which reduce our potential enjoyment of this as a cops vs robbers takedown. Cimino’s New York skyline–a photographic stunner, no question–is elevated to a co-starring role. It’s hard to know what to make of Ariane Koizumi based on her role and how she’s directed, Tracy Tzu too sincere to afford the view that she has, and oddly for a media personality, interacts with no one except for White and a camera. John Lone, who came closest to developing a memorable film character with a combination of good material and director in Iceman (1984), waltzes through like a nightclub owner in a 1940s B-movie, which is the level his character is written at. The real Stanley White served as police consultant, and the tragedy of Year of the Dragon is how little of it is as compelling as it might’ve been if it had focused on a Vietnam vet and cop as colorful as White let loose around Hollywood people.

Video rental category: Action/ Adventure

Special interest: Surveillance Society

What an incredible read and thought provoking analysis. Saw this when I was young. Watched it many times. Looking back on it through your writing was a revelation/eye opener. Great stuff. Your May theme is really engrossing on all offerings. Much enjoyed and much enlightened.

Hey Joe, as always, loved your analysis and background information… The movie itself left me kinda meh … I didn’t dislike it, but wasn’t as fun or as entertaining as let’s say Kurt Russell, in Big Trouble in Little China… Granted, that wasn’t a serious movie, but it’s still kind of why I go to the movies, to be entertained and suspend reality, etc.… Plus, after 9 1/2 weeks, Mickey Rourke has been a big disappointment… Tremendous potential but never saw him in anything really good after that… Anyway, great job thanks a lot! Always enjoy your stuff! Peace! CPZ