To Live and Die In L.A.

Secret Service pursues counterfeiter in striking yet idiotic crime thriller

Video Days orders readers to surrender their badge and gun and while suspended for the month of May, return to ten films trafficking in law and order.

TO LIVE AND DIE IN L.A. (1985) isn’t hugely flawed because it’s ridiculous, though it most certainly is absurd, as if its technical advisors were sent on vacation and scenes were shot without regard to police procedure, ballistics, logistics or logic. The film is a misfire because those who made it want credit for achieving street realism related to how Secret Service agents and counterfeiters operate, despite generating what is clearly gobbledygook for much of its running time.

Gerald Petievich grew up in Los Angeles. His father spent twenty-five years as an LAPD narcotics officer and his brother would ultimately rise as high in the department as a detective. Petievich joined the army in 1967, trained for the Army Intelligence Corps and for two years of his service was stationed in Europe. Upon his return home in 1970, rather than apply for the LAPD, Petievich took his father’s advice and with his education, chose a more financially lucrative career with the government. For fifteen years, he served as a Secret Secret agent. In addition to protecting dignitaries, Petievich was attached to the Los Angeles Strike Force against organized crime and racketeering. His speciality was anti-counterfeiting. In 1976, living in Paris during a two-year attachment to INTERPOL, Petievich made the decision to be a writer, waking at 4 AM to give himself time. He took classes at the Paris Academy of Fine Arts and when he transferred back to L.A., night courses at the UCLA Writers Program. After several years of work, his first novel Money Men was published in 1981 (eventually produced as a movie titled Boiling Point in 1993, starring Wesley Snipes and Dennis Hopper).

Petievich was working as a full-time law enforcement agent when his fourth novel To Live and Die In L.A. was published in 1984. It was about a Secret Service agent in Los Angeles who cuts corners to take down the counterfeiter who murdered his partner, growing more deplorable than his prey. Someone recommended the book to William Friedkin. Lauded as the director of The French Connection (1971) and The Exorcist (1973), Friedkin’s subsequent films would stumble with audiences and critics for the next ten years. Sorcerer (1977) is considered by many today to be a minor masterpiece worthy of mention with Friedkin’s best work, but The Brink’s Job (1978), Cruising (1980) and Deal of the Century (1983) suggested a director with his hand in the till. Reading To Live and Die In L.A., Friedkin became beguiled by the life of a Secret Service agent, someone who could be playing poker with the president of the United States one day and the next, chasing a suspect for passing a phony twenty-dollar bill at a grocery store. Friedkin optioned the film rights and began adapting a script. Assuming he’d work alone, Friedkin found himself not only consulting with Gerald Petievich on details, but assigning the author new scenes to write. He started including the Secret Service agent’s name on the script cover, and the WGA would award writing credit to William Friedkin & Gerald Petievich, based on his novel.

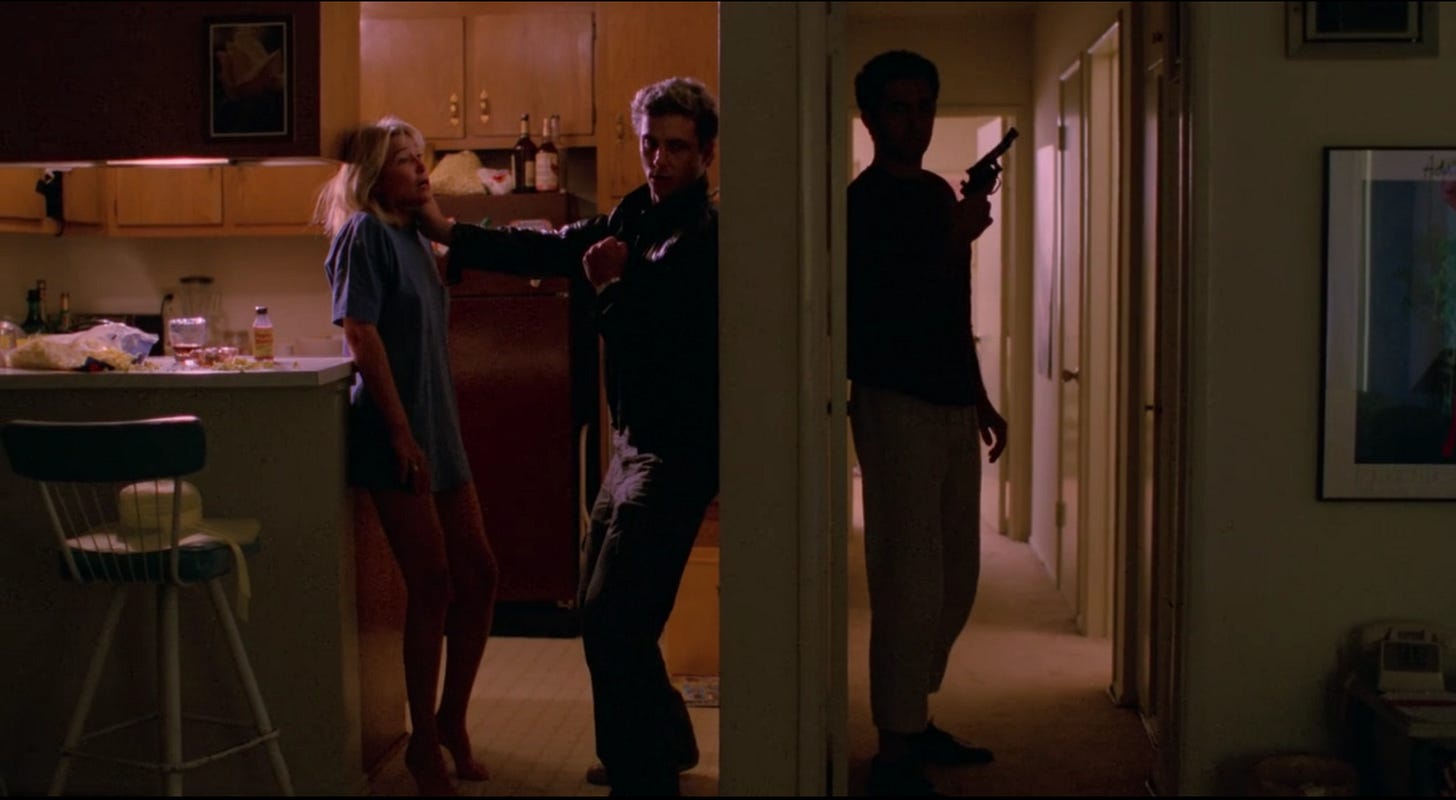

SLM Productions, a film financing partnership that had taken a toehold in the motion picture business in 1983 investing in a package of five completed pictures from Twentieth Century Fox, agreed to bankroll To Live and Die In L.A. at a production budget of $6 million, their CEO Irving Levin boarding the project as its producer. In August 1984, one of the partners in SLM, Samuel Schulman, acquired SLM and folded it into New Century Productions, taking an executive producer credit on what became SLM/ New Century’s first film. Reuniting with casting director Robert Weiner, who’d cast The French Connection, Friedkin was looking for fresh faces to keep the picture as grounded in reality as his classic police procedural, and to play rogue Secret Service agent Richard Chance, Weiner summoned Friedkin back to his hometown of Chicago to see an actor named William L. Petersen playing Stanley Kowolski in a production of A Streetcar Named Desire. Petersen, who’d never appeared in a movie, won the part. With Willem Dafoe (cast as painter turned counterfeiter Eric Masters), John Pankow, Darlanne Fluegel, John Turturro, Dean Stockwell, Steve James, Robert Downey Sr. and Debra Feuer, shooting commenced in late October 1984 in Los Angeles.

Masters’ residence was shot in Santa Monica and Chance’s beach house in Malibu, but Friedkin relied heavily on industrial locations far from the glamorous image of L.A. Chance’s bungee jump was shot on the Vincent Thomas Bridge in San Pedro, and many scenes near the Port of Los Angeles. The house where Darlanne Fleugel’s character lives–with the bridge in the background–is atop Knott Hill in San Pedro. The topless bar in Wilmington where she works was formerly Shipwreck Joey’s, later used for exterior shots of the underground boxing arena in Fight Club (1999). Masters’ desert warehouse was filmed in Palmdale, while his workshop with the Chinese letter on the loading dock door just east of downtown on the north end of the Taylor Junction railroad tracks, then and now a sketchy area. The wooden footbridge Chance chases a suspect across spanned the Southern Pacific River station next to the L.A. River. The footbridge no longer exists. The opening sequence was filmed at the Beverly Hilton, a reshoot after Friedkin wrapped principal photography and felt he needed a scene showing Chance on presidential protection detail.

With MGM/UA providing distribution, To Live and Die In L.A. opened in early November 1985 in 1,135 theaters in the U.S. Reviews were positive, most critics proclaiming the picture a return to form for Friedkin. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert penned rave reviews, Siskel crediting the film’s sense of urgency, grounded by Petersen’s performance and a car chase along the L.A. River. Ebert also commended the chase as amazing, citing Willem Dafoe as well as Petersen, and the fact that the movie teaches the viewer something about counterfeiting. Writing for the New York Times, film critic Vincent Canby admitted the film hooked him with its hypnotic score (by British New Wave band Wang Chung) and bizarre images, holding his attention while also playing as utter nonsense. Canby ultimately didn’t consider the film very well thought out. Friedkin shot quickly, printing his first take and sometimes rehearsals if he could. The result was a modestly budgeted thriller that held a spot among the top ten grossing films for five weeks and #11 for a sixth weekend post-Thanksgiving.

It’s hard to know what to do with a movie like To Live and Die In L.A. It does the complicated things beautifully while neglecting simple things to the point of audience abuse. Handing over the music to Wang Chung–between the band’s two smash singles, “Dance Hall Days” and “Everybody Have Fun Tonight”--some accused William Friedkin, who’d directed the music video for Laura Branigan’s “Self-Control” in 1984, of being seduced by MTV. But as edited by Scott Smith (son of Friedkin’s editor Bud Smith, who assumed the role of co-producer), the film is deliberate in its progression as a classic neo-noir, a dark, cynical and unsparing update of T-Men (1947), which also dealt with Treasury agents and counterfeiters. The steady hand at editing is balanced with evocative lighting by Robby Müller, the Dutch cinematographer who stepped onto this job right off of Repo Man (1984) and Paris, Texas (1984), both of which filmed in Los Angeles. Müller captures the city’s light, rust and dust with subtle wonder. Wang Chung isn't asked to lift more than their synthesizers can carry, providing seductive instrumental music to accompany a sensational theme song. Friedkin deserves credit for capturing a different side of L.A., an unhealthy side, around the city’s dingy bars, menacing bridges, and surrounded by urban desolation, mysterious warehouses. None of these spots would appear on a postcard.

While looking and often sounding terrific, To Live and Die In L.A. is chock full of stuff that is stupid. A point is made that it’s hard to tell the good guys from the bad guys these days, and in a movie, we can accept good guys who are slow, to an extent. Bad guys can’t stumble around, and in a movie where every character is a different shade of bad, that’s not good. The baloney begins immediately with a wholly unnecessary prologue which no cop in the U.S. has ever encountered on the job, the stuff of a sloppy comic book. Chance’s retirement-age partner mutters, “I’m gettin’ too old for this shit.” Both camps are terrible at their jobs. It’s unclear how Masters alerts the Secret Service to his operation and whereabouts, why someone with a fine arts background deals with that problem by shotgunning a T-man to death, then goes about his business. Chance–a thinly sketched hot dog gunning for revenge, who despite a fine William Petersen performance, is boring–falls asleep on a stakeout, gets dry gulched by and loses a state prisoner in his custody, then sets out to rob a jewel smuggler without checking out who it is he’s robbing. This level of incompetence wouldn’t be believable with Room Service, much less the Secret Service. The heralded car chase, choreographed by stunt coordinator Buddy Joe Hooker (the ultimate name for a stuntman) is a video game, with gunmen popping up magically on overpasses as if pixelated. Sega, not MTV, seems to have been the evil influence here, making anything the film has to say about corruption impossible to take seriously.

Video rental category: Mystery/ Suspense

Special interest: Surveillance Society

I am with you, Joe… I saw this movie in was kind of “meh” … I didn’t dislike it, but to underscore my ambivalence, I couldn’t remember the plot line or any of the actors in it when I saw the title of your review… And thanks to you, as always, now I know why… Great job! Peace! CPZ