The Lost Boys

World-class cast and fashion sense bleed new life into the vampire movie

Video Days is on summer vacation and idling away the afternoons in our treehouse, craving an adventure. Join us in the month of June for five films combining adolescent spirit and a journey.

THE LOST BOYS (1987) is a horror thriller by a filmmaker who’d never directed horror or a thriller, never written horror or a thriller, and demonstrates no evidence at having watched a lot of horror or thrillers. Because of this, the movie is all at once delightful and negligent, visionary and throwaway, shedding some of the conventions of the vampire tale with a world-class cast, brisk running time, narrative finesse, and taste that alternates between sensual and trashy. It’s a vintage shirt we loved, then were too embarrassed to wear, and now is back in style again.

Janice Fischer was an actor who by 1984 had spent at least fifteen years on the outside looking in as far as Hollywood was concerned. She’d played three different characters over three seasons in three episodes of the Raymond Burr series Ironside. Ironically, Fischer’s ex-boyfriend Robert Englund had spent nearly as long struggling to break out as an actor, and in 1984, was cast as a deformed serial killer named Fred Krueger in a horror movie called A Nightmare On Elm Street. By that time, Fischer had turned to screenwriting, co-creating a Christian children’s program titled The Good Book in 1982 that aired on local television. Enrolled in a film studies class in Los Angeles, Fischer met a screenwriter named James Jeremias, who’d grown up in the San Fernando Valley and worked as a grip. Jeremias had read Interview with the Vampire by Anne Rice and was intrigued by the character of Claudia, a murderous immortal trapped in the body of a five-year-old. This made him think of J.M. Barrie’s novel and subsequent play Peter Pan. Jeremias wondered: What if Peter Pan could fly and never aged because he was a vampire? Fischer & Jeremias spent five months, the summer of 1984, collaborating on a script. It was about two brothers, Michael (12) and John (8) who move to a new town with their divorced mother, Wendy. Casting a locale they thought would attract eternal children, the screenwriters chose Santa Cruz in northern California, with its ocean boardwalk and amusement park. Michael and John are tempted by a gang of thirteen-year-olds led by the enigmatic Peter, who offers them the chance to fly and never grow old, for a price. Fischer & Jeremias titled their script Lost Boys.

Before Lost Boys went to market, Janice Fischer & James Jeremias’ literary agent–Nan Blitzman of J. Michael Bloom Ltd.–shared their script with her lawyer. He slipped it to Stephanie Brody, a former executive assistant to Michael Ovitz during the formative years of Creative Artists Agency. Brody now worked as a negotiator for producers Mark Damon & John W. Hyde, co-founders of Producers Sales Organization, which had transitioned from selling American films overseas to securing financing in the U.S. for their own slate of upcoming films: 8 Million Ways To Die (1986), Short Circuit (1986), Flight of the Navigator (1986). Damon & Hyde loved Lost Boys and Blitzman assured them it could be theirs if they put in the highest bid. Ponying up $400,000, the sale to PSO was completed in January 1985. When the subject of directors came up, Jeremias suggested to Damon & Hyde that Richard Donner would be ideal, having delivered a hit horror picture in The Omen (1976), an epic fantasy in Superman: The Movie (1978) with flight choreography, and now children’s adventure, with The Goonies (1985) set for a highly anticipated release in June. As it turned out, Donner was not only looking for his next picture, but liked Damon & Hyde and agreed to read Lost Boys. Excited by its potential, Donner went to Warner Bros. Pictures’ head of production Mark Canton with Lost Boys as a project he wanted to develop. Canton liked the script and loved the idea of keeping Donner on the studio lot. Warner Bros. agreed to put up half the financing for Lost Boys in exchange for U.S. distribution rights, with PSO covering the other half of the budget, for international rights. Richard Donner would produce the film with his business partner Harvey Bernhard, and also direct.

According to James Jeremias, Donner’s first note to the screenwriters was to age the young characters up. Unlike the Goonies, Donner wanted them old enough to drive, which Jeremias assumed meant old enough to have sex. On a minor note, Donner and Warner Bros. agreed that the references to Peter Pan should be pared down, Steven Spielberg having announced his next film would be a musical version of Peter Pan and the producers worried they might be playing in Spielberg’s yard. “Wendy” became Lucy (a nod to Bram Stoker’s Dracula), while the lead vampire “Peter” became David. To give Donner the sexual tension he wanted, one of the Lost Boys, a character named Star, was changed from a boy to a girl, while the screenwriters aged Michael up to 15 ½, giving him a car at the end of the script, for his sixteenth birthday. But the version of Lost Boys that Fischer & Jeremias stuck to was about boys who resisted growing up, not teenagers crashing into adulthood. After turning in a second draft, the writers heard nothing for three months. They took a commission from Paramount Pictures to write a script, and halfway through the job, received a call from Donner summoning them to the filmmaker’s vacation home in Hawaii to start a third draft. The director had seen Fright Night (1985), a postmodern vampire tale with teenagers facing off against an unfriendly neighborhood bloodsucker, and thought that Lost Boys needed more work. Unavailable, Fischer & Jeremias were replaced by Jeffrey Boam, who was punching up the script for Innerspace (1987) at Warner Bros.

Jeffrey Boam’s marching orders were to make the boys in Lost Boys into teens, Donner uninterested in following The Goonies with another children’s adventure. Boam appraised the Fischer & Jeremias script as having a wondrous storybook quality, but little in the way of humor. He considered its resolution was weak, the boys ending up exactly who they were at the beginning. Boam added the character of Grandpa and changed the identity of the lead vampire. Donner, a kid at heart who found it difficult to sit still, had grown impatient with the rewrites. In the interim, Mark Canton handed him the next hot script acquired by Warner Bros.: Shane Black’s Lethal Weapon. Donner fell in love with its characters and even his wife, producer Lauren Shuler, urged him that he had to direct it. Donner agreed, remaining aboard Lost Boys to help the studio land a new director. Canton interviewed several candidates before settling on Richard Franklin, the Australian director of the Hitchcockian thriller Road Games (1981) whose two assignments in Hollywood had been a generally well-received horror film (Psycho II in 1983) and children’s adventure (Cloak & Dagger in 1984). Franklin huddled with Boam for several weeks on a rewrite, developing a straight horror movie set in the suburbs, but neither Donner or Warner Bros. cottoned to the movie Franklin wanted to make.

Donner was ready to give up on Lost Boys until Lauren Shuler recommended her husband consider Joel Schumacher, director of her latest picture, St. Elmo’s Fire (1985), a synthesis of post-graduate malaise–the term “Brat Pack” launched by the press to describe Schumacher’s cast–and soap opera. A graduate of Parsons School of Design whose foothold in the film industry came as a costume designer, next as a screenwriter of Sparkle (1975) and Car Wash (1976), and finally a director, beginning with a TV movie produced by Shuler titled Amateur Night at the Dixie Bar and Grill (1979), Schumacher read the script Donner sent him and met with Mark Canton to discuss directing Lost Boys. Schumacher later admitted to being dismissive of the material, telling Canton it read like “Goonies Go Vampire” and skewed young. Asked by his agent to reconsider, Schumacher did. Having been exposed to New Wave bands like Arcadia on a trip to Europe, the director pictured the Lost Boys as teenagers with moussed hair and gypsy clothes, riding stripped-down motorcycles and very sexy. Working with Jeffrey Boam, Schumacher took out nearly all remnants of J.M. Barrie or a suburban children’s film, injecting sex appeal, gore and humor. When he visited Santa Cruz, Schumacher was sold on directing Lost Boys. First Assistant Director William S. Beasley would call Santa Cruz a town lost in the sixties, like a Disneyland for hippies. (With the exception of the three principal cast members and a professional actor playing a gas station attendant, everyone in the opening credits sequence was a local sporting their own wardrobe and hair). With its transient population, Schumacher thought the setting Fischer & Jeremias had arrived on worked perfectly as a feeding ground for vampires. Harvey Bernhard would produce the picture, Richard Donner retaining an executive producer credit, and Mark Damon & John W. Hyde co-executive producer credits.

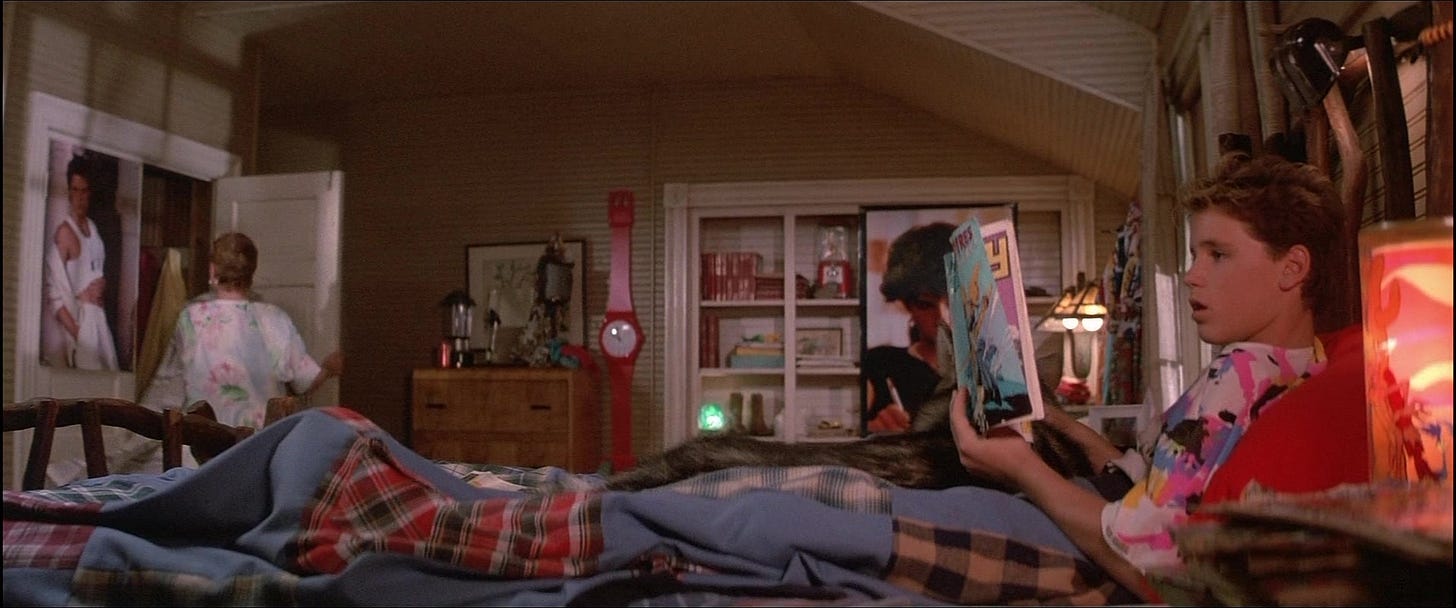

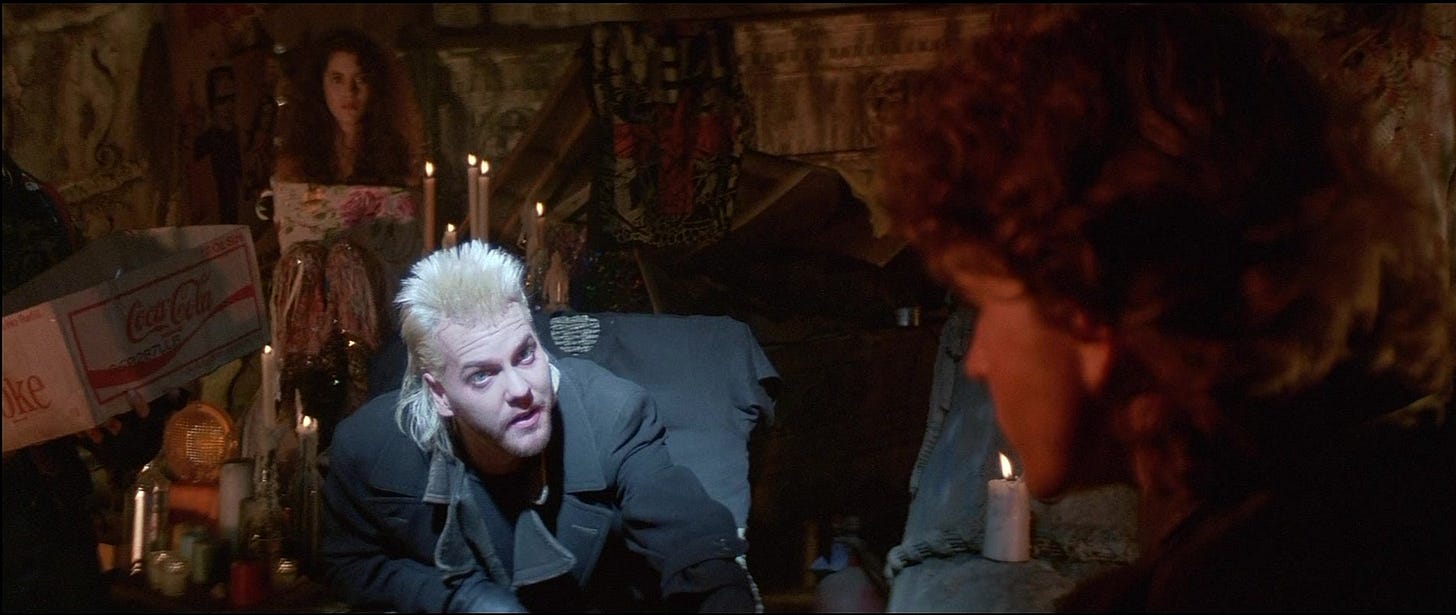

Marion Dougherty had cast Lost Boys when Donner was director and was retained by Schumacher, who zeroed in on one actor to play Michael: nineteen-year-old Jason Patric. The actor’s film debut had come in a runaway production titled Solarbabies (1986) that shot for four months in Spain. It was such an embarrassment that Patric, aware he had no leverage to turn down work, resisted making an exploitation vampire picture. He agreed to interview for Lost Boys merely to meet Dougherty, vice president of casting at Warner Bros. Over the course of six weeks, Schumacher wooed Patric to accept the part, later admitting he had no backup, certainly not an actor as young as Patric with his looks and presence. To play the younger brother, now named Sam, fourteen-year-old Corey Haim was recommended to Schumacher by his agent. Haim was a veteran child actor who played the title role in the well-received if little seen Lucas (1986). Schumacher’s dream casting to play their mother was Dianne Wiest, a member of Woody Allen’s repertory, and to Dougherty’s surprise, she agreed. Schumacher had been impressed by At Close Range (1986) and in particular, the performance of Kiefer Sutherland in a bit part, and cast him as the lead vampire, David.

Andie MacDowell’s agent suggested Billy Wirth as a Lost Boy, while Schumacher retained Brooke McCarter, who Donner had cast as David, to also play a member of the tribe. Alex Winter was a student at Tisch School of the Arts working as an actor to pay tuition and was rounded out the Lost Boys. Donner had entertained the notion of casting Jeff Cohen, who played Chunk in The Goonies, as both Edgar and Allan Frog, identical twins and Cub Scouts turned vampire hunters. Schumacher cast Corey Feldman and Jamison Newlander as teenagers emulating Rambo. The director had been spinning his wheels casting Star, seeing her in terms of Tinkerbell, a blonde waif with a pixie cut who lived on the beach. Patric suggested an actor he’d befriended on Solarbabies named Jami Gertz. They’d returned to L.A. to do a play (Out of Gas On Lovers Leap) together and after Schumacher dragged himself to a performance, the director rethought Star, changing her to a wild gypsy befitting Gertz. The cast kept getting deeper, with Edward Herrmann and Barnard Hughes agreeing to play the video store proprietor who Wiest’s character romances, and her crusty father, respectively. All the ill-fated Surf Nazis were found locally by Judith Bouley, the Santa Cruz casting director.

To serve as director of photography, Schumacher approached Michael Chapman, who’d lit Taxi Driver (1976) and Raging Bull (1980) for Martin Scorsese, and after getting a directorial career off right with All the Right Moves (1983) had misstepped with a Reader’s Digest version of the bestseller The Clan of the Cave Bear (1986). Chapman was a fan of horror films and leapt at the opportunity to light a vampire movie. Production designer J. Michael Riva was unavailable but suggested an art director who’d worked for him on The Color Purple (1985) named Bo Welch, who Riva thought was ready to move up. Welch described the look Schumacher was going for as “rustic Ralph Lauren” and his duties included designing the lair of the Lost Boys, which Schumacher had suggested would be a hotel sunken by the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. Another hire that Donner had made when planning to direct was visual effects supervisor Richard Edlund. Schumacher turned to Ve Neill for input, having met the makeup artist when she was dating his editor on Amateur Night at the Dixie Bar and Grill. Schumacher later hired Neill to do makeup for his feature debut, The Incredible Shrinking Woman (1981).

Hearing that Schumacher wanted prosthetic makeup that would retain the sexual allure of his actors, Neill was unconvinced that Edlund–who’d done the visual effects for most of the era’s monster movies, including Fright Night--was right for the job. Schumacher did reject Steve Johnson’s designs as being too similar to Fright Night and late in pre-production, on Neill’s suggestion, brought in Greg Cannom to do the prosthetic effects. In addition to his makeup effects work on The Incredible Shrinking Woman, Cannom had worked with Rob Bottin (on The Howling in 1981) and Rick Baker (on Michael Jackson’s Thriller in 1983). With four weeks of shooting in Santa Cruz before the vampire makeup needed to be ready in Burbank, Cannom and his crew were able to complete the job. Those most responsible for the look of the Lost Boys would be Schumacher, Susan Becker (costume designer), K.G. Ramsey (hair stylist) and Ve Neill (makeup artist), with the director crediting Michael Chapman for understanding the movie they all wanted to make. A camera operator on Jaws (1975), Chapman advocated doing the flying sequences as point-of-view shots, leaving much to the viewer’s imagination. Though they defy gravity, the vampires are never seen flying across the sky.

On a budget that Warner Bros. had pared by $2 million shortly before shooting–nervous the film’s lack of marketable stars would limit its appeal–Lost Boys commenced filming on June 2, 1986 in Santa Cruz on a budget of $8.5 million. At some point, the city’s mayor realized what Lost Boys was about and bristling at being referred to as “the murder capital of the world,” was assured her town’s name would be changed for the film, which it was, to “Santa Clara.” The Santa Cruz Boardwalk–the oldest amusement park in the state–was utilized, while the video store and restaurant where Wiest and Herrmann’s characters meet were shot on Municipal Wharf, which had served as a location for Harold and Maude (1971) and Sudden Impact (1983). The comic book shop–Atlantis Fantasy World–was several blocks inland and would be preserved on film before it was damaged in the 1989 Loma Prieta earthquake and torn down. The nearby Pogonip Polo Club, a historic lodge with hand-crafted wood exterior, was dressed to double for Grandpa’s house. Interiors would be shot on Stage 15 on the Warner Bros. lot. Despite its relatively small budget, the studio grew nervous over dailies that suggested a marketing-challenged movie that was both scary and funny. Studio heads Terry Semel and Bob Daly favored the latter and pressed Schumacher to declare what kind of film he was making, horror or comedy. “Yes” was Schumacher’s reply, and Mark Canton supported the director in his efforts to make a teenage rebellion film as opposed to a genre piece. Warner Bros. did alter the title, nervous a lawsuit by pop rock composer Jim Steinman over his 1981 song “Lost Boys and Golden Girls” might be pending when he heard about a movie titled Lost Boys.

The Lost Boys opened July 31, 1987 on 1.027 screens and drew mixed to negative reviews. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert turned two thumbs down, Siskel referring to it as “an overstuffed picture” with too many characters and things going on. The critic singled out Corey Haim’s character and dialogue as a bright spot but found the movie exhausting. Ebert chalked it up as a close call, a well-made film with good performances by Kiefer Sutherland and Jason Patric, but it’s most interesting material–the relationship between Dianne Weist and Edward Herrmann’s characters–at service of a gauntlet of gore to end the picture. Writing in the New York Times, Caryn James compared the take The Lost Boys offered on horror movies to Late Night with David Letterman and its take on television comedy. James wrote it up as a “hip, comic twist on classic vampire stories” and found Corey Haim enormously appealing. Theatergoers confirmed the studio’s anxieties about the movie’s appeal, failing to turn The Lost Boys into a sleeper hit. It spent four weeks among the top ten grossing films, its commercial run on par with St. Elmo’s Fire, neither hit or miss. As if the film’s audience had either been on vacation, The Lost Boys proved massively popular on videocassette and cable television. Viewers who didn’t enjoy horror warmed up to it, while those who disliked comedy in their horror appreciating it for what it was. Different.

The Lost Boys is a movie that’s a bit a victim of its own success. If its screenplay (credit to Janice Fischer & James Jeremias and Jeffrey Boam, from a story by Fischer & Jeremias) was derivative, or the film had only three or four actors in it, it would be an improvement over vampire fare like Once Bitten (1985) or Vamp (1986). Its principal actors–Jason Patric, Corey Haim, Dianne Wiest– class the material way, way, way above even the 1979 mini-series based on Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot. Kiefer Sutherland–who popped when playing a hoodlum and disappeared when promoted to a poor man’s Steve McQueen in action movies like Young Guns (1988) or Renegades (1989)--adds palpable menace as the lead vampire. Like Dracula, we don’t have faith that the new kids in town or their allies will vanquish a creature who’s been lurking around Santa Clara for as long as he has. One thing lost from Fischer & Jeremias’s original script was the Lost Boys being 100-year-old killers trapped in bodies of teenage runaways They come off as models, a new fangled take on a youth gang, nothing more, and the script settles for less complexity than Kathryn Bigelow & Eric Red did in their vampire picture Near Dark (1987). 97 minutes with opening and closing credits, it packs fourteen characters and two dogs into what today would warrant a seven-episode mini-series. Nothing in Santa Clara’s past, its supernatural predators, or its newest arrivals is explored. That Lucy has been forced from her home by her ex-husband suggests abuses that the script never touches on. Patric and Haim have good chemistry as brothers, but other than one having a motorbike and the other comic books, don’t have much to play.

Jeffrey Boam’s strong suit as a writer is action, and when his action doesn’t inform character, not much else but the costuming does. The same goes for Jami Gertz, whose character could be much more complicated than she is. How she and the boy in her care came to be initiated into the gang rather than serve as food is a movie in itself, and Patric and Gertz achieve sexual chemistry so powerful that their hazily lit sex scene proves anti-climactic. Wiest is a delight, particularly in her scenes with Herrmann, cast as a single man moving at innately perfect speed for a vulnerable divorced woman. Even the old fart played by Barnard Hughes deserves more screen time, especially after his closing line, which makes us re-evaluate the entire movie we thought we were watching. Schumacher does such a tremendous job casting and balancing his third consecutive ensemble –begun with the comedy D.C. Cab (1983)--and getting the wardrobe, hair and makeup perfect in genres that typically coast on those details that his questionable taste stand out. Chief among these is the appearance of topless and oiled-up sax player Tim Cappello for the concert scene. Cappello is a perfectly acceptable vocalist and saxophonist, but Schumacher is way more enthralled by his act than the hippies in Santa Clara–who’d be thirsting for rockers like Aerosmith–would be. Cappello’s beefcake antics are allowed to nearly derail the best scene in the film, Michael and Star laying eyes on each other for the first time (Cappello’s cover of The Call’s “I Still Believe” is an evocative song for the lovers). By thinking beyond horror or comedy, The Lost Boys classed up and reinvigorated its genres, and as a sum of its parts, is the most consistently entertaining vampire picture of its era.

Video rental category: Horror

Special interest: Kids On Bikes