The Hot Spot

Sultry Texas noir gets caught thinking above the waistline

In the month of September, Video Days plays the sucker for women who lure us into a world of danger.

THE HOT SPOT (1990) has all the pieces of what could’ve been a criminally overlooked eighties movie. It’s based on a crime novel by one of pulp fiction’s greats, who co-adapted a screenplay the filmmakers recovered from a time capsule and shot with few alterations, a 1950s noir with a 1980s cast. As talented as its actors, the musicians assembled for the soundtrack are legends. Aspiring to what the director called “The Last Tango in Texas,” its eroticism plays cool and timid. Hairpin turns of the plot are taken lazily. And the characters lack focus. It is evident what the movie does well, and yet, those qualities take too much effort to appreciate.

Charles Williams was born in San Angelo, Texas in 1909. His family relocated from West Texas to the Gulf Coast, the city of Brownsville, where Williams had some schooling before dropping out in the tenth grade. In 1925, he enlisted with the Merchant Marine and was trained as a radio operator. After spending ten years working at sea, Williams settled on Galveston Island with his wife, Lasca Foster, working as an electronics inspector. He was offered a job at the Puget Sound Naval Yard in Washington state in 1942 and a civilian defense worker during World War II, held jobs as a radio engineer and radar technician. In 1946, Williams moved with his wife and their daughter to San Francisco to begin a career as a radio inspector. That might have been the spine of his life if Williams hadn’t written a novel in the late 1940s. It was a lurid Cain and Abel tale about two brothers who lust after the 18-year-old of the title: Hill Girl. Their ménage à trois causes big trouble in the back country. Coming in by the mail, an editor at Simon & Schuster named Dan Congdon read Williams’ manuscript, and though he found the writing exceptional for a first-timer, agreed with his peers that it was too commercial for hardcover.

When Congdon left Simon & Schuster to become a literary agent, he contacted all the unrepresented writers he knew had potential. Charles Williams (not to be confused with the English author who was a contemporary of C.S. Lewis and J.R.R. Tolkien) suggested they try to publish Hill Girl, but none of the hardcover publishers Congdon pitched were interested. A year or so later, in 1949, Congdon learned that Fawcett Publications had struck a deal with Signet and Mentor to distribute their paperbacks at the same locations Fawcett offered their magazines and comic books. The deal restricted Fawcett from competing with its new partners by printing hardcover books in paperback, but didn’t say anything about paperback originals. The new imprint–Gold Medal–would become the home of John D. MacDonald early in his career, as well as several authors of hardboiled fiction. Upon publishing a short story (They’ll Never Find Her Head) in Uncensored Detective magazine in December 1950, Williams had quit his job to write full time. Published by Gold Medal in 1951, Hill Girl would go on to sell 2.5 million copies in paperback. Quick on its heels, Williams shipped Big City Girl and River Girl in 1951. Combining crime and forbidden romance, most of Williams’ novels were about how poorly men understood women.

Critics began to take notice of Williams with his fourth book. Published in 1953, Hell Hath No Fury was narrated by Harry Madox, newly arrived in a town where the business district is one street wide and three blocks long. Thirty years old, the drifter finds work as a used car salesman. Hot, bothered and lazy, Madox starts thinking with the wrong organ, bopping from a romance with a sweet loan officer named Gloria to a fling with his boss’s shapely and much younger wife, a jezebel named Dolores Harshaw. Harry can only keep making bad decisions for so long before he makes a disastrous one: setting a structure fire as a distraction while he robs the town bank. Fleshing out a story Manhunt magazine printed in September 1955 (titled Flight To Nowhere) into a thriller titled Scorpion Reef, the author would begin moving ambidextrously between hardboiled noir and seafaring suspense. Williams had the misfortune of writing standalone thrillers at a time when they weren’t very popular in the U.S. Editors compelled writers of genre fiction to devote themselves to a series, like John D. MacDonald’s Travis McGee mysteries, or Donald Westlake cranking out the Parker potboilers as “Richard Stark.”

Williams would complete a duology featuring yacht broker John Ingram and his partner Rae Ingram (née Osbourne) in Aground (1960) and Dead Calm (1963), but grew bored of writing the same characters or situations. Publishing against the grain, Hollywood didn’t know what to do with Williams either. In 1961, he adapted Hell Hath No Fury to screenplay with a friend named Nona Tyson. They used Robert Mitchum as their model for Harry Madox, but their script was buried for twenty-eight years. While the film industry considered paperbacks to be low brow or trashy, readers in France, Italy and Spain loved American pulp fiction. Williams’ novel Nothing In Her Way was adapted into the French language caper comedy Banana Peel (1963) starring Jeanne Moreau. Back in Hollywood, Universal Pictures did buy The Wrong Venus and commissioned Williams to adapt his novel, which became the horribly reviewed sex comedy Don’t Just Stand There (1968) starring Robert Wagner and Mary Tyler Moore. Following the death of his wife in 1972, Williams bought a parcel of land in Northern California where he planned to build a house, but according to Congdon, living in a trailer and waiting for the weather to improve only isolated the writer and made him more depressed. Williams returned to Los Angeles and with the support of Nona Tyson, managed to complete what would become his last novel, Man On a Leash, published in 1973.

By this time, Nona Tyson was working as a secretary at Universal Pictures. The studio had assigned her to a 24-year-old TV director who Universal president Sid Sheinberg had signed to a generous deal many thought was in excess of the kid’s talent. The kid, Steven Spielberg, would remember Tyson fondly for at least three reasons: 1) Tyson handed Spielberg the April 1971 issue of Playboy, which included a short story by Richard Matheson titled Duel. She thought the material would be perfect for her boss to direct as a TV movie. He made inquiries, got the job and airing in 1971, the dark fantasy about a motorist stalked by a homicidal truck driver would become Spielberg’s calling card to feature films, namely The Sugarland Express (1974) and Jaws (1975). 2) After two previous secretaries had tried, Tyson learned to read her boss’s handwriting, Spielberg a mediocre student who would later be diagnosed with dyslexia. 3) Tyson’s hair and wardrobe were so retro 1940s that many who encountered her on the Universal lot assumed she was in costume. This might explain her affinity for Charles Williams and his fiction. Tragically, the widowed author took his life in his Van Nuys apartment in 1975.

Roughly twelve years later, British writer/ director Mike Figgis was making the rounds in Los Angeles following a very well received debut film in the noir tradition titled Stormy Monday (1988), a U.S./ U.K. co-production starring Melanie Griffith, Tommy Lee Jones, Sting and Sean Bean. United Artists commissioned Figgis to adapt Charles Williams’ Hell Hath No Fury under the title of its 1981 reprint: The Hot Spot. What would’ve been Figgis’ sophomore film garnered good actors in Sam Shepard, Anne Archer and Uma Thurman. A poorly managed shell of what the studio had been before its acquisition by MGM in 1981, the project fell apart. Waiting in the wings were Orion Pictures, which had a solid track record of producing modestly budgeted films the major studios couldn’t or wouldn’t make. Picking up Mike Figgis’ script for The Hot Spot in turnaround, Orion offered directing duties to Dennis Hopper. The character actor, improbably, given his exploits, had survived the late sixties and seventies, emerging from drug and alcohol rehabilitation in the mid-1980s to book one killer role after another: evil incarnate in Blue Velvet (1986), an alcoholic basketball coach in Hoosiers (1986), a dope peddler in River’s Edge (1987).

Hoosiers had been produced and distributed by Orion Pictures, who were familiar enough with Dennis Hopper to book no objections when Sean Penn suggested he direct Colors (1988). In a direct assault on the color coordinated comedies or musicals of the type Charles Williams had been writing against in the sixties, Hopper’s debut as a director, Easy Rider (1969), had ushered in a decade of young men, and every once in awhile, young women, bucking the status quo writing or directing gritty films that resisted or rejected convention. In the wake of Easy Rider, Hopper had only directed two other films, one a drama in Canada whose director fell out at the eleventh hour. Colors, which tackled the epidemic of gang violence in Los Angeles mostly from the point of view of two LAPD officers, was made in something of a loose if not unconventional style. Hopper and the film were embraced by critics, and audiences turned out in greater numbers than they had for any movie featuring Penn. The director wouldn’t be as lucky with his next picture, the thriller Backtrack, in which Hopper both directed and starred, opposite Jodie Foster. Vestron Pictures orphaned the movie in bankruptcy, recutting and releasing it as Catchfire (1990) to no one’s satisfaction.

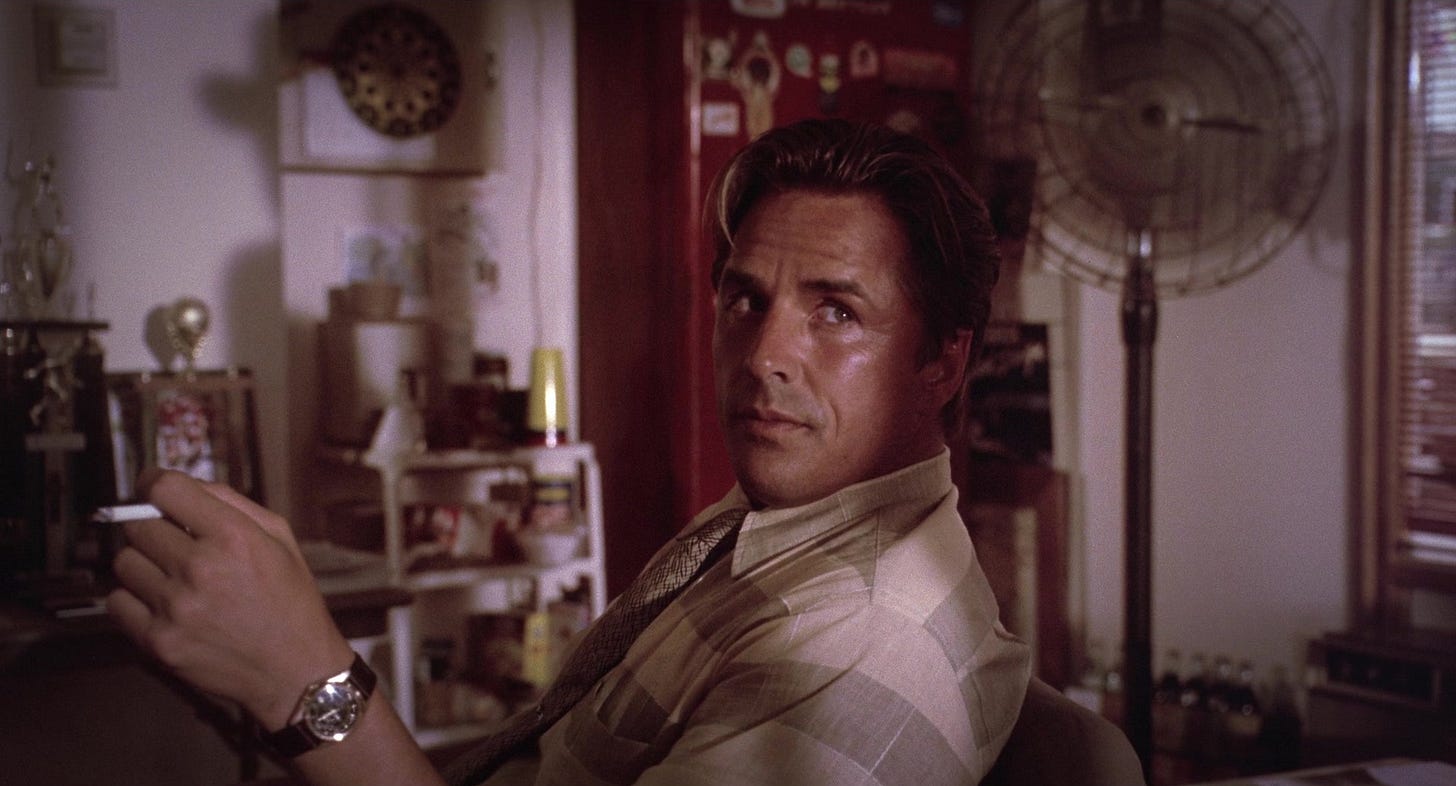

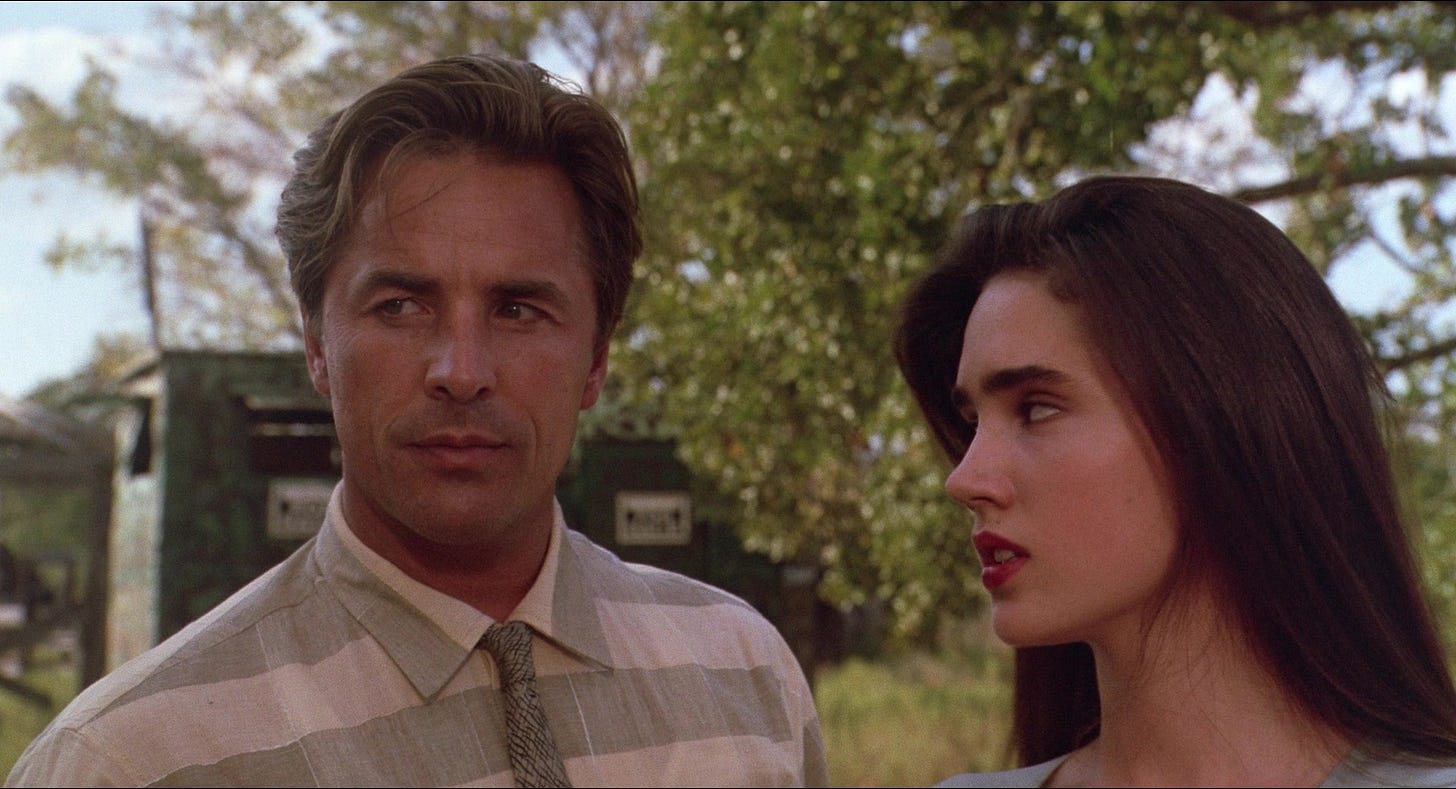

As the disaster of Backtrack inched forward, Orion and Hopper agreed he could make something out of Mike Figgis’ script for The Hot Spot. Hopper’s primary collaborator was Paul Lewis, a unit production manager whom Jack Nicholson had introduced Hopper to in 1968 and had worked on every film Hopper directed. Following the success of Colors, Lewis was promoted to producer. No longer available, Sam Shepard, Anne Archer and Uma Thurman dropped out of The Hot Spot one by one. They were replaced by better choices for each part: Don Johnson, Virginia Madsen and Jennifer Connelly. A stellar supporting cast was assembled: Charles Martin Smith as a car salesman, Jerry Hardin (possibly the hardest working actor in television at the time) as Madox’s cuckolded boss, Barry Corbin and Leon Rippy as the town’s sheriff and deputy sheriff, Jack Nance (of David Lynch’s Eraserhead and nearly every film Lynch had directed since) as a squirrely bank owner, and William Sadler as “Frank Sutton,” a nefarious cracker who shares a shady past with Gloria.

The Hot Spot was scheduled to begin shooting in late summer 1989 in Central Texas on a budget of $10 million. Hopper–who’d recently worked in the Austin area as an actor on The Texas Chainsaw Massacre Part 2 (1986)--was friends with locals like Willie Nelson and Bud Shrake and didn’t pass up a chance to visit the Lone Star State’s capitol when he could. Late in pre-production, Paul Lewis dug up the Charles Williams & Nona Tyson draft of Hell Hath No Fury and brought it to Hopper’s attention. While he knew how to direct the Mike Figgis script, Hopper preferred to make the Williams & Tyson version. In Figgis’ draft, Madox’s motivation for robbing the bank was explained by a flashback in which he watches his father forfeit the family farm to bankers. Rather than a heist-driven take, the Williams & Tyson script was a mood piece in which Harry Madox’s backstory wasn’t more detailed than framing him as a stranger in town. Orion Pictures–whose business model was trusting filmmakers they respected to shoot screenplays the studio liked, granting them creative freedom to do so under a certain budget–approved the eleventh hour switch in scripts, perhaps for no other reason than Hopper wanted to and it was economical. (According to Don Johnson, he found out about their new script three days before shooting.) Tod Davies, a graphic designer married to writer/ director Alex Cox, did an uncredited polish on the script with Hopper, her husband having done some rewrite work on Backtrack. The WGA would award writing credit to Charles Williams & Nona Tyson, based on the novel Hell Hath No Fury by Williams.

In mid-August 1989, filming got underway in Taylor, Texas, notable for the visual aesthetic its downtown offered. The town of 11,000 was a commutable distance northeast of Austin, where cast and crew were put up at the Austin Marriott Downtown. While the used cars, clothing and hairstyles signaled the movie was set in present day, the filmmakers took advantage of locations and a pace of life that hadn’t changed since the 1950s. Texas-based production designer Cary White built “Harshaw Motors” on a vacant lot in downtown Taylor and refurbished a couple of buildings, including a former bank dressed to look like it was open for business, and the empty First National Bank on Main/ 2nd, outfitted with pyrotechnics for the warehouse fire sequence. Several scenes were picked up in Austin. The interior of the Red Rose Adult Nightclub stood in for the topless bar Johnson’s character wanders into. The interior of a drug store and the exterior of Gloria’s boarding house were also filmed in Austin. Harry and Gloria’s swimming scene, as well as a flashback in which Jennifer Connelly and Debra Cole played sunbathing topless, were filmed at Hamilton Pool Preserve, a scenic state park with waterfall and grotto in Dripping Springs. Frank Sutton’s shack was filmed in La Grange, where Johnson was working on October 4 when his wife Melanie Griffith went into labor at Brackenridge Hospital in Austin. Johnson made it back in time to cut his daughter Dakota Johnson’s umbilical cord, and by 5pm, was back in La Grange for work.

As talented as the cast, the musicians assembled for the soundtrack were legends. Jack Nitzsche, an arranger for record producing impresario Phil Spector in the sixties who’d worked with Ike & Tina Turner and played keyboards for The Rolling Stones, was contracted to compose the music. Nitzsche had been Academy Award-nominated for his eerie score to One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975) and later won Best Song, co-writing “Up Where We Belong” for An Officer and a Gentleman (1982), which he also scored. Hopper had been wanting to work with Miles Davis, who according to the soundtrack album liner notes, he’d known since he was 17, when Davis “punched out” a heroin dealer and threatened Hopper with worse if he started on smack. To Nitzsche’s amazement, the jazz great agreed to lend his trumpet to The Hot Spot, and with Miles Davis on board, a jazz and blues dream team formed. Guitar legend John Lee Hooker was supported in the studio by Taj Mahal (steel guitar, electric banjo), Roy Rogers (slide guitar), Tim Drummond (bass) and Earl Palmer (drums). None of the musicians read a script or watched film. Nitzsche provided a scene summary and the emotion he was after–”disappointment,” “escalation”--and the band improvised, with Hooker lending his trademark growls and hums. Davis arrived on day four of the jam session to record his sections, the other musicians taking the opportunity to hang out with the cutting edge bandleader, who’d grown up in East St. Louis with an affinity for the blues music John Lee Hooker and the others were knee deep in.

Dennis Hopper had almost as much riding on the success of The Hot Spot as his actors. Don Johnson had yet to pull audiences watching him on Miami Vice into theaters with the movies he’d made while on hiatus from his television series, the romance Sweet Hearts Dance (1988) and cop thriller Dead Bang (1989). Virginia Madsen had worked nonstop since her debut in Class (1983) but a box office hit had evaded her, while the same was true of Jennifer Connelly, who as a teenager, had bewitched those who’d discovered her in Once Upon A Time In America (1984) and was transitioning into adult roles. Meeting the film’s discouraging demand, Orion sealed a dismal box office fate for The Hot Spot by opening it in only 23 theaters in the U.S. on October 12, 1990. Critics were lukewarm. Many drawn to the dreamlike quality of David Lynch’s films didn’t find much to Dennis Hopper’s casually paced genre piece. In contrast, those turned off by Lynch’s tastes preferred Hopper’s cool restraint. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert split along those lines. Siskel called the film a pale imitation of Lynch, focusing his negative review on Don Johnson, who the critic thought stood around posing like a male model. Ebert framed the movie as a 1950s film, with the Virginia Madsen and Jennifer Connelly characters owning it, locked in a fight for Johnson. With its bizarre love triangle, lurid crime and rural setting reminiscent of Blue Velvet, Ebert called The Hot Spot a David Lynch movie that worked.

The Hot Spot is set at such an unhurried pace that the viewer is lulled to sleep watching it. This might please those looking to hang out with skilled actors or musicians, of which, the movie does offer a bevy. Ueli Steiger, a Swiss born cinematographer who’d lit Jennifer Connelly in Some Girls (1988) and within ten years would be lighting monstrously budgeted movies like Godzilla (1998), shows a fine eye for capturing the infinite horizons and tempestuous skies of Texas, and The Hot Spot utilized the Lone Star State as fine as any film shot there. While Miles Davis’ trumpet is too pensive for a backwoods noir that needed its fingers popping garments loose, John Lee Hooker’s wicked blues guitar and vocals are a much finer fit for the hot and bothered picture that was shot, and Hooker’s contributions to the soundtrack are a treat for the ears. Virginia Madsen doesn’t get a lot of much screen time, but rather than react to the plot, compels others to react to her, playing an overheated housewife toying with people to feel alive. Her performance is game and loaded with wit. William Sadler, who’d jump from backwoods in The Hot Spot to a blizzard in Die Hard 2 (1990) as its chief villain, also understands what type of movie he’s in and delivers to the hilt. Hopper places a lot of faith in Virginia Madsen (younger sister of actor Michael Madsen, who’d play his share of rockabilly hoodlums too) and directs her to one of her finest performances. He doesn’t seem to realize how good Sadler is, though, directing Don Johnson to regard him as little more than a cranky customer.

While Colors benefited from its lack of cohesion, a genre piece like The Hot Spot needed more of it. The screenplay, or Hopper’s interpretation, leaves much of the novel untapped. Hell Hath No Fury was a consummate caper, loaded with whiskey-breathed lingo, tempestuous atmosphere and a well-designed plot. The book also introduced characters the reader gets caught up in wanting to get away with the score. Don Johnson, too good-looking to convincingly play a drifter capable of breaking a beer bottle over anyone’s head, occupies the movie like a piece of furniture. Harry’s comeuppance needed a proper lead-in, and Johnson’s performance lacks the virility an actor like Robert Mitchum could summon standing still. His character is simply too blank to love or hate. Jennifer Connelly–responsible for The Hot Spot flying off video store shelves by leaving less to the imagination than she would in the comedy Career Opportunities (1990)--is kept at a distance by Hopper, playing a male fantasy with the mannerisms of a fashion model struggling to appear lifelike in motion pictures. Hopper blows an opportunity to set two bored or lonely women in competition for the last attractive man in the county. Set on a used car lot, The Hot Spot does outfit its characters with magnificent wheels: a 1959 Studebaker Silver Hawk for Harry and a pink ’59 Cadillac Series 62 convertible for Dolores.

Video rental category: Mystery/ Suspense

Special interest: Femme Fatale