The Fly (1986)

Physics gone awry and sexual chemistry collide in horror-filled romance

In the month of October, Video Days is looking out for scaredy cats, counting down to All Hallows’ Eve with seven horror movies in ascending scariness.

THE FLY (1986) is a love story dressed up for Halloween. Knocking on the door wearing some disgusting makeup, it’s the story of two people falling in love. The “what if” it throws the viewer is: What if one of the lovers was stricken with a terminal disease that deteriorates their body, forcing their partner through some tough decisions? The disease could be cancer, but in this powerful reimagining of The Fly (1958), the filmmakers fuse relationships with science fiction and horror in a way that, despite some stomach-churning moments, is grounded in romance.

George Langelaan was an English citizen who’d grown up in France. He became a Field Security policeman with the British Army, escaped Dunkirk, and participated in the invasion of Normandy in 1944. After the war, Langelaan became a staff correspondent for UPI, and in terms of literary success, his first published fiction was historic. Appearing in the June 1957 edition of Playboy magazine, The Fly was a short story in which one François Delambre is phoned at night by his sister-in-law Hélène with tragic news. Arriving at his brother’s laboratory with the local magistrate, they discover Charles Delambre has been killed under a hydraulic press, his head and one arm destroyed. Hélène admits to killing her husband but offering no explanation, is placed in an asylum. François learns from his nephew that prior to the murder, Hélène had her son searching for a housefly with a white head. When François questions his sister-in-law about the fly, she agrees to tell-all. Her husband was working on a matter transmitter which, if successful, could teleport objects like a television signal. Charles becomes withdrawn, refusing contact with his wife. To her horror, Hélène discovers her husband’s head and arm have been replaced by those of a giant fly, the result of an accident in the matter transmitter.

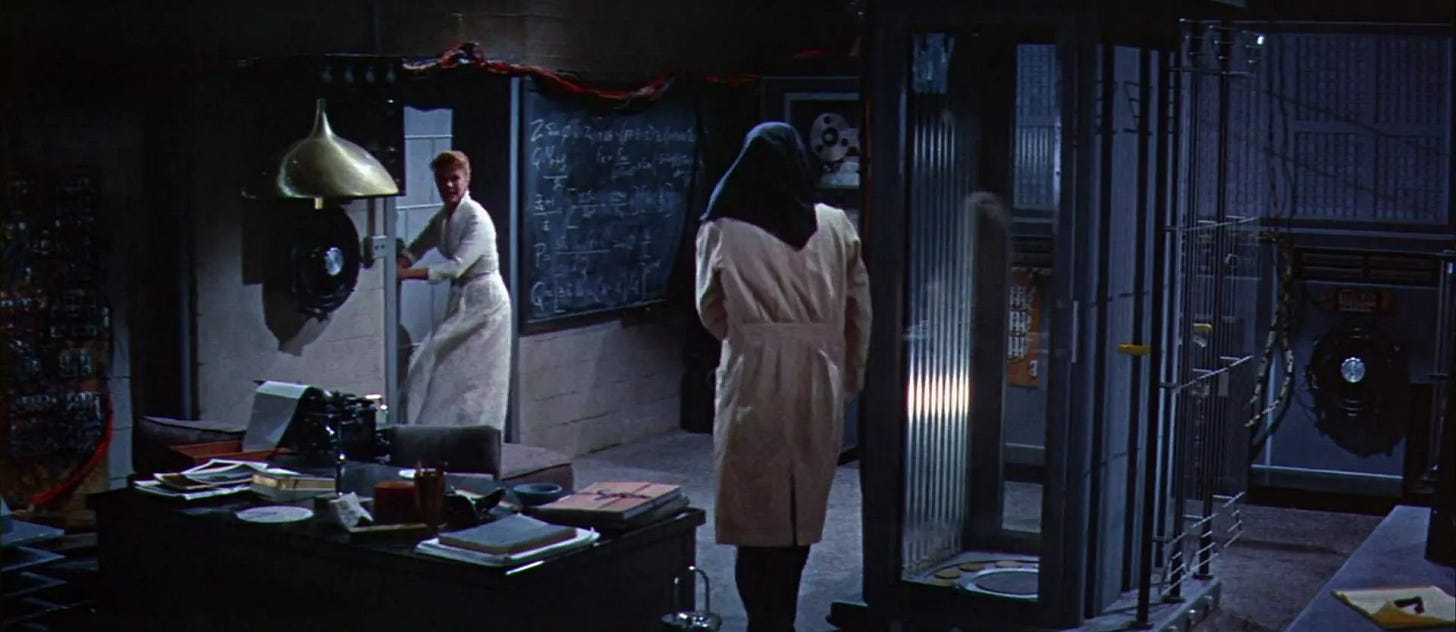

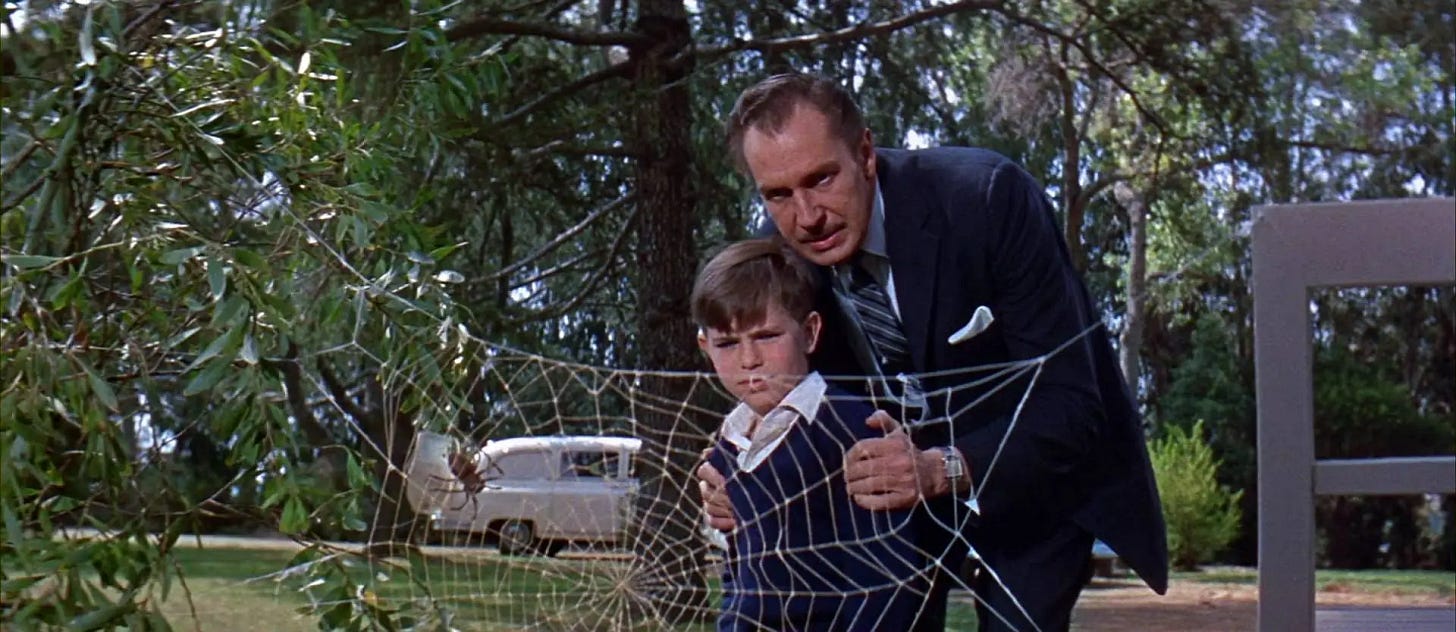

When Playboy awarded The Fly honors as the best fiction the magazine published in 1957, Hollywood came calling. Regal Pictures had a contract with Twentieth Century Fox to supply the studio a pipeline of B-pictures, and Kurt Neumann had been cranking them out. The Desperados Are In Town (1956) was a western that played on the bottom half of the bill with the Elvis Presley-starring Love Me Tender (1956), while two science fiction pictures–Kronos (1957) and She Devil (1957)--produced and directed by Neumann were finished so quick they ran on the same bill. Neumann saw The Fly under similar bargain lines, but Fox, which hadn’t made a science fiction film since the prestigious The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951), took the popularity of the short story as a signal that The Fly merited quality production. Novelist James Clavell was commissioned to adapt a screenplay for Neumann to produce and direct. A Fox contract player named Al Hedison was cast in the title role. To play the sympathetic François Delambre, Vincent Price was selected. Price, a versatile actor, had starred in the 3-D horror hit House of Wax (1953), but few of his pictures could be classified as thrillers. Fox set a production budget of $480,000, using DeLuxe Color and framing the film in CinemaScope to compete with television. Audiences propelled The Fly to box office Fox hadn’t enjoyed since Peyton Place (1957), with as much as $4 million in ticket sales. Price was flooded with like offers, and with House on Haunted Hill (1958) and The Tingler (1959) for producer William Castle, and Roger Corman producing House of Usher (1960) and The Pit and the Pendulum (1960), Vincent Price became part and parcel with horror film from The Fly onward.

In 1984, literary agent Melinda Jason suggested that one of her clients, Charles Edward Pogue, work with a manager she knew named Kip Ohman to mold his screenwriting career. Ohman shared with Pogue a copy of the George Langelaan short story The Fly. Ohman’s interest in it was that Twentieth Century Fox owned the remake rights, and he knew that Pogue had a connection at the studio, with its VP of production David Madden and to some degree, studio president Joe Wizan, whose wife had introduced Pogue to his agent. Pogue had never heard of the short story, nor seen the movie based on it, nor did he consider himself a science fiction writer. He screened The Fly, and didn’t think much of it. The Al Hedison character was not only a passive protagonist, but once he completed his transformation, was robbed of facial or vocal expression. Those were provided in spades by his wife as she descended into madness.

Pogue pitched the idea of a remake to a producer named Stuart Cornfeld, who had a deal with Fox. Cornfeld agreed that a redo of The Fly as a head-swapping movie wouldn’t work, but that a metamorphosis might. Their pitch to Fox won them a commission to write a screenplay. Despite David Madden fostering the project, Joe Wizan passed on Pogue’s script. The studio president also refused to option Cornfeld the rights to sell elsewhere. After a good deal of effort, the producer won a concession: Fox would provide distribution for a remake of The Fly if Cornfeld could raise financing. The first and only place he’d go was Brooksfilms, the production company founded by Mel Brooks. Cornfeld had produced Brooksfilms’ inaugural picture, Fatso (1980), which Brooks’ wife Anne Bancroft wrote and directed, and served as an executive producer on their critical and commercial wonder The Elephant Man (1980), directed by David Lynch. Both films were similar to Pogue and Cornfeld’s take on The Fly: a man is trapped inside a body which society finds repellent.

Stuart Cornfeld delivered the script on a Friday, and the following Monday, received a call from Brooks in which the comic writer/ actor/ producer/ director expressed in no uncertain terms that he felt the script was garbage. Cornfeld ascertained that Brooks’ problems were in the first ten pages, and that he hadn’t read much further. Cornfeld compelled him to finish the script, and when he did, Brooks agreed to develop the project. Feeling this required a writer of his own choosing, Brooks hired Walon Green to generate a new script. Cornfeld found that Green’s work, while not without merit, was a step backward. Pursuing a director, he sent Pogue’s script to David Cronenberg, writer/ director of Rabid (1977), Fast Company (1979), The Brood (1979), Scanners (1981), Videodrome (1983) and an adaptation of the Stephen King novel The Dead Zone (1983) that, starring Christopher Walken and Martin Sheen, had crossed over to a wider audience. As Cronenberg held firm on making his films in Canada, his demand in Hollywood had gone up. Deep in rewrites and pre-production on what would be his first international picture, an adaptation of Philip K. Dick’s short story We Can Remember It For You Wholesale, retitled Total Recall, Cronenberg was unavailable.

Cornfeld focused on Robert Bierman, a British director of two impressive short films–an 18-minute thriller titled The Dumb Waiter (1979) and an adaptation of the D.H. Lawrence short story The Rocking Horse Winner (1983)--to make his feature film directorial debut. As Bierman arrived in Los Angeles, Charles Edward Pogue was put back on the payroll to work with him on rewrites. Cornfeld was leaning toward hiring Christopher Tucker, who’d designed the prosthetic makeup in The Elephant Man, for The Fly, which like the Lynch picture, would shoot in England. In October 1984, management at Fox was shaken up when Barry Diller was installed as studio chairman, with Lawrence Gordon replacing Joe Wizan as president. The Fly was the only project the new regime had ready to shoot and they moved forward with it, planning to start production May 1985. Breaking for Christmas, everyone was shocked by news that Bierman’s daughter had been killed while on a family vacation in South Africa. Pre-production shut down as Bierman departed to be with his family. After a month, the director confided to Brooks that he’d lost his desire to direct The Fly. The producer gave Bierman another three months to think it over.

When Bierman conceded he was still not in the right frame of mind to direct, the search for a new director began. By this time, David Cronenberg had realized his vision for Total Recall–to star William Hurt and adhere to Philip K. Dick’s mind-bending short story–was not the Raiders of the Lost Ark on Mars that producer Dino De Laurentiis wanted. Cronenberg exited the project and was suddenly available. His agent listed his fee to rewrite and direct The Fly at $750,000. Mel Brooks had worked with Barry Diller on The Elephant Man while the mogul was running Paramount Pictures, and Brooks wrote him a letter expressing the opportunity they had to make a similarly prestigious motion picture with David Cronenberg, if they took him off the market for what he was worth: $1 million. Diller agreed to meet that sum and with Cronenberg on board, finance and distribute the picture. Cronenberg’s assessment of Charles Edward Pogue’s script was that it was a terrific rethinking of The Fly, the screenwriter mining its potential for body horror so well, it was as if Cronenberg had thought of the idea himself.

What Cronenberg didn’t particularly like about the script were its characters and dialogue, which he rewrote, alone. A racing enthusiast, Cronenberg renamed the protagonist Seth Brundle, after Formula One driver Martin Brundle. He also cut the first 17 pages of Pogue’s script, but based virtually 100% of his rewrite on the structure Pogue had established (the WGA would award screenwriting credit to Charles Edward Pogue and David Cronenberg). The director insisted on shooting the film in Canada, as well as working with the Canadians he’d established a strong rapport with on his previous pictures: director of photography Mark Irwin, editor Ronald Sanders, production designer Carol Spier, composer Howard Shore. Though not Canadian, creature effects designer Chris Walas had worked on Scanners and with a staff of thirty at CWI in San Rafael, California, began work on the effects for The Fly in September 1985. To best facilitate Brundle’s makeup, Walas campaigned for Cronenberg to cast an actor without prominent ears or nasal bridge. Scripts went out to John Malkovich and Richard Dreyfuss. They were among several leading men who passed, according to Cronenberg, because they were dubious they’d be able to act through the makeup.

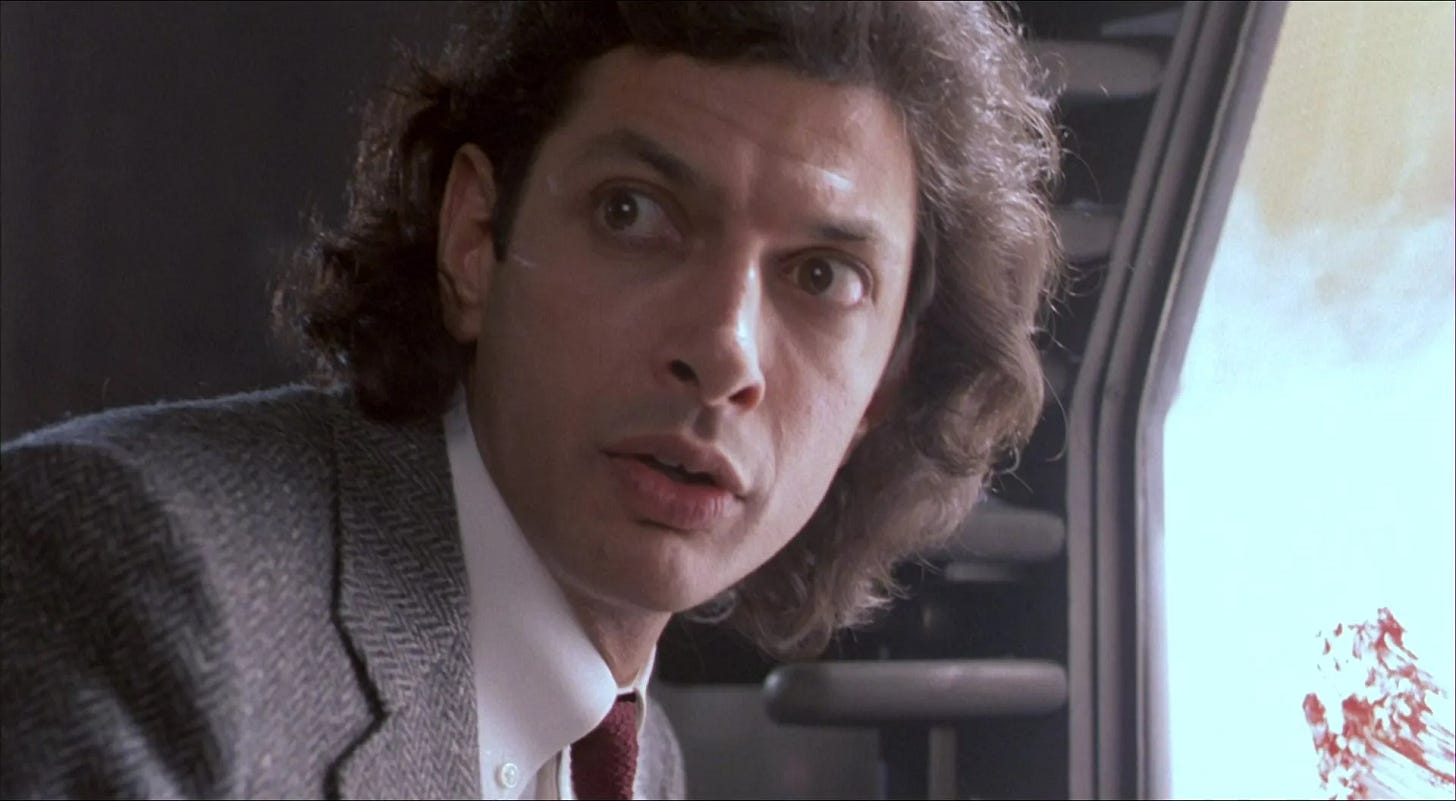

Jeff Goldblum–whose facial features were the opposite of what Walas and his effects team considered compliant–agreed to take the part. At 33, Goldblum had found a place for himself in the repertory companies of filmmakers Philip Kaufman–for Invasion of the Body Snatchers (1978) and The Right Stuff (1983)--and Lawrence Kasdan–in The Big Chill (1983) and Silverado (1985)--but his leading man credentials were limited to the caper Into the Night (1985), which critics and audiences had ignored earlier in the year. According to Cornfeld, Goldblum’s casting was unilaterally opposed by Lawrence Gordon, but unphased about his own job security, the studio president told Cornfeld that while he thought Goldblum was a mistake, he was the filmmakers’ mistake to make. For the part of tech reporter Veronica Quaife, who plummets into a love affair with Brundle after visiting his lab, Goldblum suggested Geena Davis, who the actor had met on the set of Transylvania 6-5000 (1985) and was dating. Davis was the first of several actors Cronenberg met with for the role and despite some skepticism that a couple should play one on film, Davis won the part by virtue of her audition.

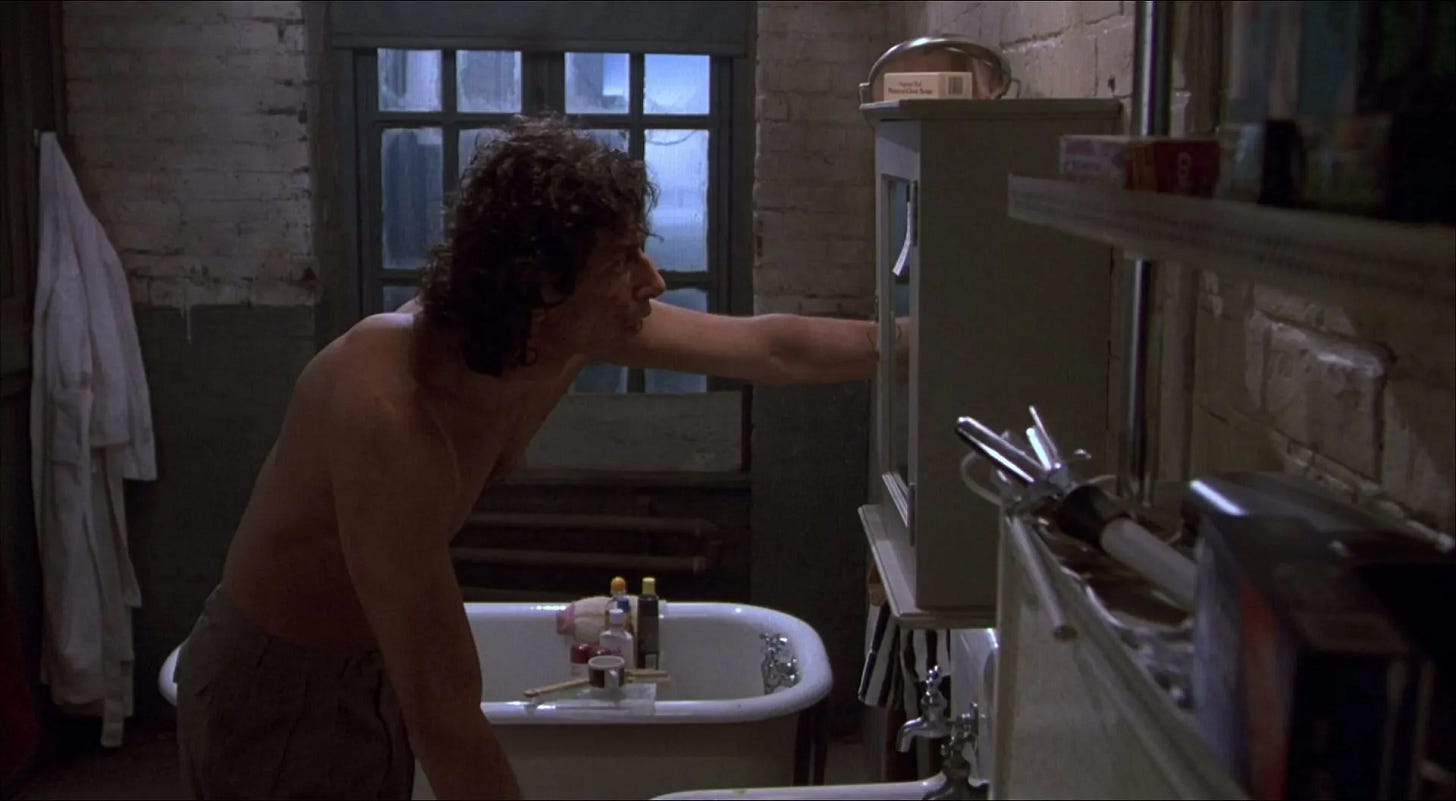

The film’s romantic triangle was completed by John Getz, who’d played the fall guy in the first film by the Coen Brothers, Blood Simple (1984), and was cast as Veronica’s boss and former lover. The Fly commenced filming in December 1985 in Toronto. The science expo that opens the film was shot in the Art Gallery of Ontario. Industrial exteriors for Brundle’s lab were filmed in the Distillery District, while interiors were shot mostly at nearby Kleinburg Film Studios. No country or city is ever specified in the movie, but the CN Tower in Toronto is visible during a rooftop scene. Chris Walas, whose team at CWI had been responsible for designing and building a menagerie of creatures in Gremlins (1984), had been wary of remakes and of mimicking the transformation effects of movies like An American Werewolf In London (1981) or The Thing (1982). A selling point for Walas with The Fly was that the actor playing Brundle–far from transforming into another monster–would require makeup that held up while he delivered dialogue, including a good deal of exposition. In support of the actor’s performance, the appliances Walas built gave Goldblum the most freedom around his eyes and his mouth.

Chris Walas–who with CWI’s Stephen Dupuis received an Academy Award for Best Makeup, while Jeff Goldblum’s agents lobbied on his behalf for an Oscar nomination that would not come–credited the actor for taking the time to rehearse in his makeup, testing what he could and couldn’t do with it. Some of CWI’s work ended up being too much of a good thing. A scene in which Brundle fuses a baboon and a stray cat in the telepod, the hybrid of which attacks him and nearly escapes before he beats it to death with a pipe, left such a bad taste in the mouths of test audiences that it was cut. So was what would’ve been the next scene, in which Brundle scales the exterior of his lab and tears an appendage out of his mutating body. As scripted and shot, The Fly was to end with Veronica waking from a nightmare in which her abortion goes horribly wrong, followed by a dream in which she gives birth to a human-butterfly hybrid. Unsatisfied with the effects, Cronenberg cut the dream, and placed the nightmare at another spot in the picture. To promote The Fly, Bryan Ferry was commissioned to co-write (with Nile Rodgers) and perform a song, “Help Me.” Cronenberg realized the track didn’t work over the end credits and stuck it in the bar scene, nearly inaudible.

The Fly opened August 15, 1986 on 1,195 screens in the U.S. Like many leading newspaper critics, Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert were enjoying vacations and didn’t review the movie when it opened, but on an episode of At the Movies dedicated to their picks for the best films of 1986, Siskel ranked The Fly #10 and Ebert admitted the movie was in his top twenty for the year. Offering an opposing view in the New York Times, Caryn James wrote: “This is intense, all right, but not scary or sad, or even intentionally funny. The one consistently strong element in the midst of Mr. Cronenberg’s haywire, tone-deaf direction is Jeff Goldblum’s performance, a just-controlled mania that fills the screen without threatening to jump off it. As he becomes a creature, we can still recognize his voice and see his eyes peering through the increasing layers of rubber goo that encase him. But like The Fly itself … even he is finally lost in the gloop.” Anticipation was high for the horror remake, which opened #1 at the U.S. box office, spending five weekends among the top three grossing pictures in the country (with Stand By Me and Top Gun) and eight weekends in the top ten. Its critical and commercial success birthed a sequel, The Fly II (1989), produced by Brooksfilm, directed by Chris Walas and starring Eric Stoltz and Daphne Zuniga. It struggled to justify its existence or appeal to audiences.

Even without a romance at its core, The Fly (1986) would be good, a propulsive modernization of the mad scientist sub-genre of science fiction or horror. The script by Charles Edward Pogue and David Cronenberg is exciting on an intellectual and visceral level, asking questions and respecting the temperament of the viewer to hear them out. It neutralizes the “mad” and emphasizes the “scientist” in the mad scientist movie. The writing and directing reveal very deliberately how Brundle’s social anxiety (What if we could eliminate traffic congestion?) has kept his work a secret, as well the skepticism his hypothesis (teleportation) would receive. In a preview of the horror to come, we watch Brundle’s experiments fail, before pillow talk with Veronica (unlike baboons, his girlfriend offers feedback) leads to eureka. If the picture wasn’t R-rated, it would work as an educational film on the scientific method. An interesting side effect to approaching the science with respect is that the filmmakers develop empathy for their characters. Before the film begins, Brundle seems to have realized that his breakthroughs are meaningless with no one to share them with, and his success gives him confidence to approach an attractive reporter and invite her back to his lab. He’s a bit naive about women, and doesn’t foresee that Veronica would covet a professional breakthrough of her own, something to garner her the respect that her career and love life have been lacking.

Jeff Goldblum–so perfectly cast as an anxious genius falling in love it boggles the mind that any other actors would’ve been seriously considered–was graduating from quirky ensemble player to neurotic leading man, while Geena Davis was on a similar trajectory, from a comic sidekick/ research assistant in Fletch (1985) to a leading lady/ reporter with this role. In their second of three pictures together, Goldblum & Davis have wonderful chemistry, playing all the notes of a couple: attraction, vulnerability, connection on multiple levels. They look fantastic together, so much that it would be implausible if everything worked out for their characters. The horror Brundle is exposed to as he learns what he’s becoming from the inside out, and Veronica’s anxiety over what she can and cannot do to help him, are relatable, and easier to watch as science fiction or horror than they would’ve been if Brundle was deteriorating from leukemia or AIDS. Given the green light by Mel Brooks (who declined an executive producer credit) not to hold back, David Cronenberg delivered. Not only does the director depict the grotesque manner in which Brundle’s body begins to fall apart and his digestive system switch to an insect one, but Cronenberg approaches the material with an operatic flourish, evident from the first cue of Howard Shore’s thunderous musical score. A Law & Order approach would’ve made it too easy to pick the fiction apart from the science, like how Brundle has managed to keep his work hidden from the corporation funding it, or why one of his test baboons is allowed to roam freely around the lab. Cronenberg’s ardor for hyper reality actually makes the movie harder to dismiss, not less.

Video rental category: Horror

Special interest: Science Run Amok