The Commitments

Roddy Doyle's novel conceives one of the best fictional bands in film

THE COMMITMENTS (1991) balances laugh-out-loud funny dialogue with soul music discussions, soul music jam sessions and soul music performance by one of the best fictional bands ever put on film, with vocals recorded live. These halves are juggled by filmmakers who, as serious music fans, are uninterested in the pageantry of being a recording star and keep the narrative humming with the sense of pride that creating art can bring its creators, particularly those hungry for work in a Third World country.

Roddy Doyle was born and raised in Kilbarrack, a neighborhood five miles north of Dublin’s city center which, as he aged, had its fields paved over as the Republic of Ireland’s capital grew, making room for more families, mostly working class, to move in. He earned a degree from University College, Dublin and by 1976, was teaching high school English and geography in his old neighborhood, at Greendale Community School. More than content to spend his life as an educator, Doyle started writing in the evenings. A novel titled Your Granny’s a Hunger Striker went unpublished, but a play, Brownbread, was staged in September 1987. Listening to his students trying to talk over each other in an effort for their voices to be heard, Doyle had the beginning of an idea for a new novel. While most of his students listened to heavy metal, punk or ska music, their instructor was inspired by two recently published non-fiction books he’d read: Nowhere To Run: The Story of Soul Music by Gerri Hirshey, and Sweet Soul Music: Rhythm and Blues and the Southern Dream of Freedom by Peter Guralnick. This led Doyle to write a fiction about a white band who’d play Dublin soul. They called themselves the Commitments.

Doyle and a friend named John Sutton–working from a £5,000 bank loan, the application of which was longer than the book–decided to self-publish Doyle’s novel under the auspices of King Farouk Press, “farouk” rhyming slang for “book.” The Commitments consisted almost entirely of dialogue in local patois, with scarce descriptions and no mention of politics. They printed 3,000 copies. Due to how few novels by Irish authors were published, it was reviewed favorably in the newspaper Northside People, while Ireland’s version of Rolling Stone magazine (Hot Press) printed a scathing review. Another copy found its way to the U.K. publishing house Heinneman, where an editor pulled it out of the slush pile, fell in love with it, and helped get The Commitments published properly, in 1988. A few days after its publication, Lynda Myles, who’d produced a political thriller starring Gabriel Byrne and Greta Scacchi titled Defense of the Realm (1985), optioned the film rights, her producing partner Roger Randall-Cutler raising the money for the option and to pay Roddy Doyle to adapt a screenplay, which he hadn’t insisted on, but was curious to give a crack, having never written a script before.

After working with Doyle to complete a draft, Myles commissioned screenwriters Dick Clement & Ian La Frenais, who had nearly twenty-five years experience writing in television and film, perhaps known to North American audiences for the Judge Reinhold/ Fred Savage body switch fantasy Vice-Versa (1988). The duo used what Doyle had scripted as foundation and added to it, notably the character of Mr. Rabbitte, an Elvis Presley-obsessed father of the book’s lead character, band manager Jimmy Rabbitte. Clement & La Frenais were living in Los Angeles and when they met a fellow Englishman for lunch, director Alan Parker, handed him a copy of the novel. Parker had signed to direct a film version of the Broadway musical Les Misérables for TriStar Pictures, with plans to start shooting in January 1991 after the stage version had run its course. He missed home, having shot his last several pictures–Angel Heart (1987), Mississippi Burning (1988), Come See the Paradise (1990)--in the States. Parker had grown up in the north London neighborhood of Islington, where Victorian houses had been split into multi-use tenements and many of his peers in the 1960s yearned to escape, perhaps in a band. Parker not only laughed out loud reading Doyle’s novel, he recognized its environment.

Lynda Myles and Roger Randall-Cutler set up financing with Beacon Communications, a film finance company newly co-founded by Armyan Bernstein and Tom Rosenberg, who’d met at the University of Wisconsin at Madison. With Parker agreeing to direct The Commitments, he headed with Beacon to the Cannes Film Festival in May 1990. A production budget of roughly $12 million was raised through pre-sales. John Hubbard and Ros Hubbard, the husband and wife who ran one of the U.K.’s top casting agencies, had already hit the ground in April, searching Dublin pubs and clubs for musicians to audition for one of the twelve band members in the film, sometimes visiting six venues per night. Parker, who’d directed the musicals Fame (1980) and Pink Floyd: The Wall (1982), had decided that rather than cast actors who’d have to fake the music, he wanted musicians he could instruct how to act. Thinking a recording star in the role of the band’s sage, trumpet player Joey “The Lips” Fagan, would be great for publicity and that “Irish” plus “soul music” equaled “Van Morrison,” Parker met with the singer/ songwriter. The audition did not go well, with Morrison mocking the script and asking why the Commitments weren’t performing his music.

In June 1990, the filmmakers arrived in Dublin to commence music and acting auditions for what they later estimated were 3,000 locals. In what they dubbed “Deaf Aid,” 64 bands came and went over three days (most if not all the musicians Jimmy endures listening to while putting the band together in the film’s audition sequence came from this group). After each hopeful sang or played, they read a scene from the script. By mid-July, Parker had whittled the prospective band down to 100 candidates, who were called back to sing or play with a live session band. Bassist Paul Bushnell was among the session players, and drawing from the libraries of Atlantic, Motown and Stax recordings, had built a set list of seventy-five songs for the Commitments to potentially perform. Parker promoted Bushnell to musical director for the band. By early August, the cast was set. Of the twelve band members, only Johnny Murphy (as Joey “The Lips” Fagan) and Bronagh Gallagher (as Bernie) had any professional acting experience.

Robert Arkins played several instruments and was leader of Housebroken, whose music he described as “rap-dance.” He was a finalist to play the film’s phenom singer Deco, but won the part of manager Jimmy Rabbitte, doing only a dash of singing in the role. Andrew Strong, the sixteen-year-old son of one of the session vocalists, belted out “Mustang Sally” in his final audition and impressing Parker with his reading of the script, was cast as Deco. Glen Hansard was known locally as the leader of the rock band The Frames and took the part of rhythm guitarist “Outspan.” Félim Gormley was a session saxophone player who’d worked with Billy Joel and The Rolling Stones. Curiously, despite being Dublin musicians, none had met before. They were put through five weeks of dramatic rehearsals in the morning and musical rehearsals in the afternoon. As an exercise, Parker had the three girls (Bronagh Gallagher, Angeline Ball, Maria Doyle Kennedy) read the boys’ parts, the women being the stronger actors and allowing the men with their musicians’ ears to hear how their dialogue should sound. Dick Clement & Ian La Frenais took part in the rehearsals, incorporating new dialogue and often reassigning it based on what they heard. Parker likened it to preparing for a play, and by the time the group commenced shooting in September 1990, everyone knew their role.

Though Doyle had set his novel in the fictional northside neighborhood of “Barrytown,” he’d based it on his home of Kilbarrack. Finding nothing remotely cinematic in the suburb, Parker cribbed together a patchwork of urban locations that reminded him of where he’d grown up, naturally making Dublin a much more significant character than it had been in the book. Over 53 days, the production shot at 44 different locations throughout the city. For authenticity, Parker insisted on recording the vocal performances live, and sound engineers developed a system for doing it. Out-of-phase speakers were used to blast backing tracks at high volume, providing music for Strong, Gallagher, Ball, and Doyle Kennedy to sing to (otherwise, lip synching would have been necessary to match sound to image in the edit). With Twentieth Century Fox providing distribution, The Commitments opened in mid-August 1991 in the U.S. and Ireland. Reviews were mixed. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert split, with Siskel calling the film “joyful but empty” and likening it to a redo of Fame, while Ebert credited its verisimilitude, inventing a band that sounded like an actual band. Improvisation had led to a soundtrack loaded with profanity, which led to an R-rating, which may have impacted the film’s commercial prospects (Parker joked that Bronagh Gallagher, who’d appear as Rosanna Arquette’s smoking buddy in Pulp Fiction, broke the record set by Joe Pesci in GoodFellas for variations on the word “fuck”). Never expanding beyond 560 theaters, the film spent two weekends among the top ten grossing films in the States. It found its audience globally on videocassette.

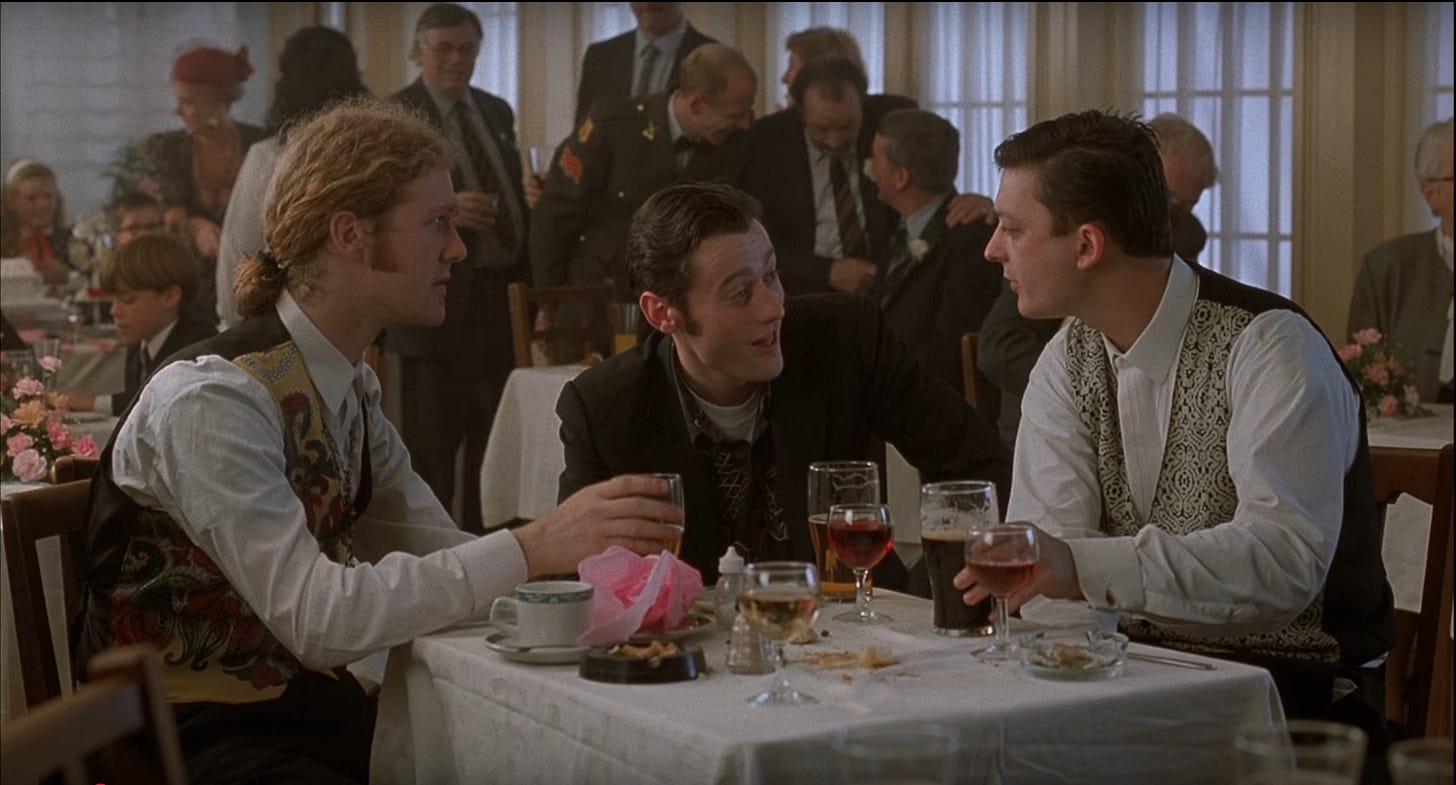

The first treat to unwrap with The Commitments–more internationally known and universally embraced than the novel Roddy Doyle won the Booker Prize for in 1993, or the two pictures Alan Parker received Academy Award nominations for directing–is its dialogue. Parker was known as a visual stylist, grouped with directors like Ridley and Tony Scott or Adrian Lyne for evocative lighting or frenetic editing. The Commitments is the best material he ever had, and other than shooting the dramatic scenes very loose and fashioning the performances with stage lighting and punctuated editing, Parker doesn’t unpack tricks to keep the film, which qualifies as a low budget indie, exciting. The dialogue, ably assisted by Colm Meaney as Mr. Rabbitte (“U2 must be shittin’ themselves,” he deadpans after appraising the boys) is fresh and riotously funny. Much of it is taken directly from Doyle’s novel, but clipped, cleansed and at times doled out to different characters in the script by Doyle and Clement & La Frenais, like this exchange, with Outspan and bassist Derek (Ken McCluskey) begging Jimmy to get them out of wedding gigs by managing their lounge act, fronted by a buffoon named Ray (Philip Bredin).

JIMMY: Why do you want me to manage it?

OUTSPAN: Cos you know everything about music, Jimmy. You had that Frankie Goes To Hollywood album before anyone heard of ‘em. And you were the first to realize they were shite.

JIMMY: What’s shite is what youse were playing up there.

OUTSPAN: We have to play that stuff for a wedding.

JIMMY: What do you call yourselves?

DEREK: And And And.

JIMMY: And And fuckin’ And?

DEREK: Well, Ray is thinkin’ of putting an exclamation mark after the second “And.” He says it’ll look deadly on the posters.

OUTSPAN: You don’t like it? Do you think it should go at the end?

JIMMY: I think it should go up his arse.

OUTSPAN: Well, we’re not married to it.

DEREK: Oh, no.

At 117 minutes, The Commitments has so many characters and so much ground to cover–assembling the band, rehearsing the band, dangling success in front of the band–it doesn’t stop to give a slide presentation on economic malaise or social decay in Ireland, and those expecting lessons–for things like what horses are doing in urban housing projects–might be disappointed. Music fans are treated to characters we get to know based on the types of music they love, the artists they credit as influences, or how they acquit themselves as musicians, like the drummer who quits because he’s so enraged by Deco’s behavior he’s worried being around him will create a parole violation. From the casting to the arrangements, the Commitments acquit themselves as a great fictional band. There isn’t one musical performance in the film that isn’t enthralling, the ladies’ performance of Aretha Franklin’s “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man” a stand-out. Advance knowledge of soul music or pop culture are not required. What the film reinforces is that short of becoming a superstar, the beauty of artistic endeavor is the sense of self-worth it instills in an otherwise dreary existence.

Video rental category: Music Drama

Special interest: Fictional Bands

Better put your flat feet on the ground! Thank you, thank you thank you Joe. I loved this film… The commitments! It’s raw, it’s gritty, Motown music, dialogue, you just feel like these people are real and struggling hard for their moment in the Spotlight That undoubtedly is gonna be the highlight of their lives… But like every local hometown hero from some backwater Podunk high school, reality sets in you earn your money as a used car salesman Living in a Doublewide with a nondescript Local girl and three kids… You’ve peaked at age 17 and live the rest of your life getting your vicarious thrills and meaning from larger sports or rock ‘n’ roll heroes. Loved this movie and all the backstory information you provide Joe, thanks, Peace! CPZ.