The Blob (1988)

'50s creature feature revived as ferocious, all-out practical effects extravaganza

In the month of October, Video Days is looking out for scaredy cats, counting down to All Hallows’ Eve with seven horror movies in ascending scariness.

THE BLOB (1988) aces three tests for horror filmmaking. Its screenwriters go for broke, soliciting the viewer to question the taste and perhaps sanity of those responsible. The casting is good, each actor doing their part in a wider campaign. And its makeup effects are spectacular, working in tandem with the other tests to infect the viewer. A remake of the cute, low budget 1950s monster picture of the same name, this is a pleasure chest for anyone who’s used the phrase “practical effects,” perhaps to complain about the state of modern movies.

Philadelphia-based motion picture distributor Jack H. Harris produced The Blob (1958) as an independent film, nearly everyone involved working on their first real movie. His friend Irvine H. Millgate, president of the Mental Health Consultation Center in Hackensack, New Jersey, came up with a story idea: a meteorite crashes near a small town and unleashes a gelatinous, carnivorous mass that grows in size the more victims it digests. To direct, Harris hired Irvin S. Yeaworth Jr., son of a Presbyterian pastor, who with his wife, ran Good News Productions, one of the country’s largest producers of films on Christian or charitable themes. The couple lived dormitory-style with thirty adults and their families in Chester Springs, Pennsylvania, where they all worked together on films which Good News sold to television or churches, two institutions which were part and parcel of American life in the 1950s. Yeaworth Jr. had worked his way up to co-directing a feature, a cautionary tale titled The Flaming Teen Age (1956). Working with Harris on a creature feature that could play to a much larger audience, they came up with a title: The Glob. A minister who Yeaworth Jr. knew–Theodore Simonson–adapted a screenplay, which Kate Phillips, a B-movie actor in the 1930s and ‘40s who’d written two teleplays for the TV series Lux Video Theatre in 1954, was hired to complete a two-week polish.

On a production budget of roughly $110,000, Harris made The Glob entirely in Pennsylvania, using Phoenixville for exteriors, and shooting interiors at Valley Forge Film Studios, a facility where westerns were being filmed on the East Coast when Hollywood was a lemon grove. While the actors–which included twenty-seven-year-old “Steven” McQueen is his film debut as a leading man–wrapped their work in 31 days, the special effects took as many as nine months to complete. Retitled The Blob, possibly to avoid infringing on the copyright of an illustrated book about evolution titled The Glob, Paramount Pictures paid $300,000 to acquire the picture, distributing it on the top half of the bill with I Married A Monster From Outer Space (1958). The studio set expectations that their acquisition could gross $1.5 million. Opening the year NASA formally organized, and Forrest J. Ackerman began publishing Famous Monsters of Filmland, The Blob doubled Paramount’s projection and grew into one of the most popular monster pictures of its time, though unlike The Thing From Another World (1951) or Them! (1954), two white-knuckling science fiction thrillers shot in black & white, Harris’ DeLuxe Color production, with amateurs in front of and behind the camera, was regarded as silly fun.

Twenty years later, Chuck Russell finished the University of Illinois Chicago early and drove to Los Angeles, knowing he wanted to work in the movie business. His first job was sweeping sound stages. Next, he gigged as a production assistant on a TV commercial. Russell began working his way up, from a production supervisor on Bobby Jo and the Outlaw (1976) to a unit manager on a TV movie based on Last of the Mohicans (1977). He was entrusted to produce an early title from Dimension Films, The Great American Girl Robbery (1979), aka Cheerleaders’ Wild Weekend. Working as an executive producer for producer Bruce Cohn Curtis on the Compass International Pictures horror movie Hell Night (1981), Russell met Frank Darabont, who was starting his film career in the same spot Russell had been in five years previous, albeit as a driver who was always late. Russell liked Darabont enough to hire him on his next production for Curtis, The Seduction (1982) starring Morgan Fairchild. Keeping his desire to direct close to the vest, Russell had been writing most of his time in California. A costume designer on The Seduction named Linda Bass suggested that if Russell was serious about writing and directing, he should read a M*A*S*H spec script that Darabont had written and consider working with him as a writing partner. For slightly more money than Darabont was earning as a PA, Russell commissioned him to generate a first draft of an idea he had for a youth comedy, Russell rewriting Darabont and vice versa.

Russell’s big break reached theaters in the summer of 1984, when Twentieth Century Fox opened the independently produced science fiction thriller Dreamscape–co-written by Russell in collaboration with original screenwriter David Loughery and director Joseph Ruben, with Russell serving as associate producer with Bruce Cohn Curtis–on more than 800 screens. With no one interested in the scripts he was co-writing with Frank Darabont, Russell switched into producer mode, hunting for film rights to a property that would be taken seriously. Russell found Jack H. Harris in Los Angeles and called him. The producer had rejected offers to remake The Blob along the lines of a comedy, but Russell’s intent to make a relentless horror thriller, coupled with his enthusiasm, won Harris over. He optioned the remake rights to Russell on two conditions: Harris be credited as a producer and receive an invitation to the premiere. Russell’s prestige was on the ascent as the producer of two successful comedies–Girls Just Want To Have Fun (1985) and the Rodney Dangerfield blockbuster Back To School (1986)--but as a screenwriter and first-time director, no one was interested in financing the remake of The Blob he’d co-written with Darabont.

Their “no’s” included New Line Cinema, the mini-studio built on the success of A Nightmare on Elm Street (1984). What New Line needed was a writer and director to continue the Freddy Krueger franchise, the creator of the original film Wes Craven having completed a draft with Bruce Wagner before reaching an impasse with the studio. With The Blob as a writing sample, Russell was offered the job of rewriting and directing Nightmare on Elm Street 3. Given eleven days to dial in their script, Russell booked a cabin in Big Bear with two desks and, working with Frank Darabont, wrote through a high fever to complete what they would subtitle Dream Warriors. Loaded with terrific characters and exciting horror set pieces, the script attracted Heather Langenkamp–who’d sat out A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (1985)--to reprise her role from the original, while an actor named Patricia Arquette was chosen to co-star, in her first movie. Russell’s directorial debut opened in February 1987 and was a monster hit, selling more tickets than several of the year’s most anticipated films.

The success of A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors got the attention of producers Elliott Kastner and Andre Blay. Kastner had produced dozens of pictures, including The Missouri Breaks (1976) and Angel Heart (1987), while Blay was the founder of Magnetic Video, the first company to license, market and distribute films for the home video market. Blay sold Magnetic Video to Fox in 1979 and after serving as the CEO of Fox Video for two years, was installed as CEO of Embassy Home Entertainment. Despite producing a handful of high-quality pictures–This Is Spinal Tap (1984), The Sure Thing (1985), The Emerald Forest (1985) — Embassy was sold by Coca-Cola to Nelson Entertainment before Blay could build it into a mini-major studio, not unlike New Line. Blay and Kastner purchased a 60% stake in the film distribution and home video operation of Cinema Group Entertainment, which had opened the horror movie Witchboard (1987) on more than 1,000 screens in March 1987. Chuck Russell had let his option on The Blob lapse, and New World Pictures picked it up in August 1986. One year later, the rights were available, and Russell let Kastner and Blay know that he wanted to direct the remake he’d written with Frank Darabont.

Cinema Group announced that they would produce and, at a budget of $15 million, finance a remake of The Blob, setting Memorial Day weekend 1988 as their release. (Russell would pin the production budget he was given at $11 million). With limited resources and less time, Russell began hiring some of the best special effects technicians in the industry. Designing and creating the glutinous predator fell on creature effects designer Lyle Conway, who’d built Audrey II, the carnivorous talking plant in Little Shop of Horrors (1986). Designing makeup for everything else–mainly the blob’s melting victims, be they animatronics, prosthetic makeup, or miniatures–was 23-year-old Tony Gardner, who’d worked with Rick Baker on Michael Jackson’s Thriller (1983), Starman (1984) and Harry and the Hendersons (1987). Gardner was put in charge of thirty-three makeup artists and given seven months to complete 41 effects shots for the film. Dream Quest Images, under visual effects supervisor Hoyt Yeatman, utilized blue screen photography, matte paintings, and stop motion animation for several sequences. To serve as director of photography, Russell hired Mark Irwin, based on the Canadian cinematographer’s work lighting six horror films for David Cronenberg, namely The Fly (1986).

First-billed among the three main teenage characters was Kevin Dillon, a standout in Platoon (1986) as a bloodthirsty G.I., playing a juvenile delinquent in the off-season ski resort where Russell & Darabont had staged their action. Cast as a cheerleader was Shawnee Smith, a child actor who’d begun to transition into young adult roles in Iron Eagle (1986) and Summer School (1987). Donovan Letich, playing her suitor, the high school quarterback, had gotten his start in TV sitcoms at the same time as Smith. Jeffrey DeMunn, Candy Clark, Joe Seneca, Del Close, Paul McCrane (the gang member dunked in toxic waste in RoboCop), Art LeFleur and Jack Nance completed the cast. With TriStar Pictures agreeing to distribution, shooting got underway in January 1988 in Abbeville, Louisiana. The seat of Vermilion Parish had a picturesque business district, including a city hall at the end of its Main Street as called for in the script. Louisiana had been selected over California or Georgia due to its weather forecast, which called for no snow in January. With the film set over one day and mostly after dark, three weeks of night filming took place in Abbeville, which inspired the name of the town in the film to be christened “Arborville.” The production returned to Los Angeles for three more weeks of night shooting, where patches of Griffith Park stood in for countryside. Interiors were completed at Valencia Studios.

Racing to make a summer release, The Blob opened August 5, 1988 on 1,081 screens in the U.S. Critical response was largely negative. Writing in the New York Times, Janet Maslin compared the remake unfavorably to the “funny, revealing, often dull and never frightening souvenir of the era” that inspired it, predicting that this version, while “more spectacular” would be forgotten. Offering a passionate defense, Dave Kehr of the Chicago Tribune wrote: “Despite its proudly proclaimed ‘multimillion dollar special effects budget,’ Russell’s Blob is every bit as trashy, unpretentious and entertaining as the original must have been when it turned up on double bills with I Married A Monster From Outer Space.” Michael Wilmington, writing for the Los Angeles Times, was unimpressed. “But more wounding than the uneven tone or thin dialogue of this Blob is its increased scale. The ‘50s low-budget classics were exactly that: low budget. Much of that appeal–and almost all of the original Blob’s–lies in their economy of means. Here, economy is the first victim chewed up by the pestilence.” The Blob opened in competition with only one new release, and strangely, it also starred Kevin Dillon, Disney believing they had the more commercial offering in The Rescue, a family-friendly action vehicle.

In its opening weekend, The Blob failed to muster the ticket sales of Cocktail, Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Die Hard, Coming To America, A Fish Called Wanda, Midnight Run, or (in its tenth weekend of release) Big. By its second weekend, Chuck Russell’s sophomore film had fallen out of the top ten grossing films in the country. The director would later cite managerial turnover at their distributor for a marketing campaign that didn’t make his movie look very exciting. It was true that one month before The Blob started shooting, TriStar’s parent company Coca-Cola had begun writing off several commercially disappointing films produced by the regime of outgoing Columbia Pictures chairman David Puttnam, and that Coke was looking to balance the books on all their entertainment holdings headed into the nineties. However, the executive leadership at TriStar that had chosen to distribute The Blob had all kept their jobs. The horror remake simply didn’t generate the word of mouth that propelled A Nightmare on Elm Street into a sleeper hit, nor did its monster have the recognition that Freddy Krueger did in the sequels. Those who would embrace The Blob were a growing demographic of fandom who’d devoured news of the monster remake in magazines like Fangoria or Cinemafantastique and heralded The Blob as one of the best in its class.

Like the mutant ameboid from outer space, The Blob moves so fast that it doesn’t stop to build atmosphere or existential dread, as John Carpenter and David Cronenberg did with their reimagining of 1950s B-movie monster pictures: The Thing (1982) and The Fly. These films are character-centric–very similar to plays–and drenched in doom, both more powerful for it. Carpenter and Cronenberg aspired to more than 1950s B-movie monster pictures. Chuck Russell seems positively tickled to be making a 1950s B-movie monster picture and embraces it with a hold-my-latte-and-watch-this vibrato, taking advantage of more resources and also better material than he’d worked with in his twelve years in the business. As drawn up by Russell & Darabont, their remake is an action/ horror or horror/ adventure picture, but its suspense is double-edged. The writers keep inventing new ways for the viscous creature to attack–crawling across the ceiling, slithering through plumbing, oozing out from a movie theater projection booth (as a homage to the set piece from the 1958 film) or hiding inside the corpse of a victim it devoured from within. What the blob does when it catches a new victim keeps changing too, getting worse all the time. Like a stomach turned inside out, acid coating its cotton candy exterior, the blob grows larger and moves faster with each body it consumes, smothering the terrified residents of Arborville as it melts their skin, muscle tissue and organs. The filmmakers convey what a miserable way this would be to go, digested alive, and are almost as merciless, building empathy for a number of characters and then turning them into horrified puddles of goo.

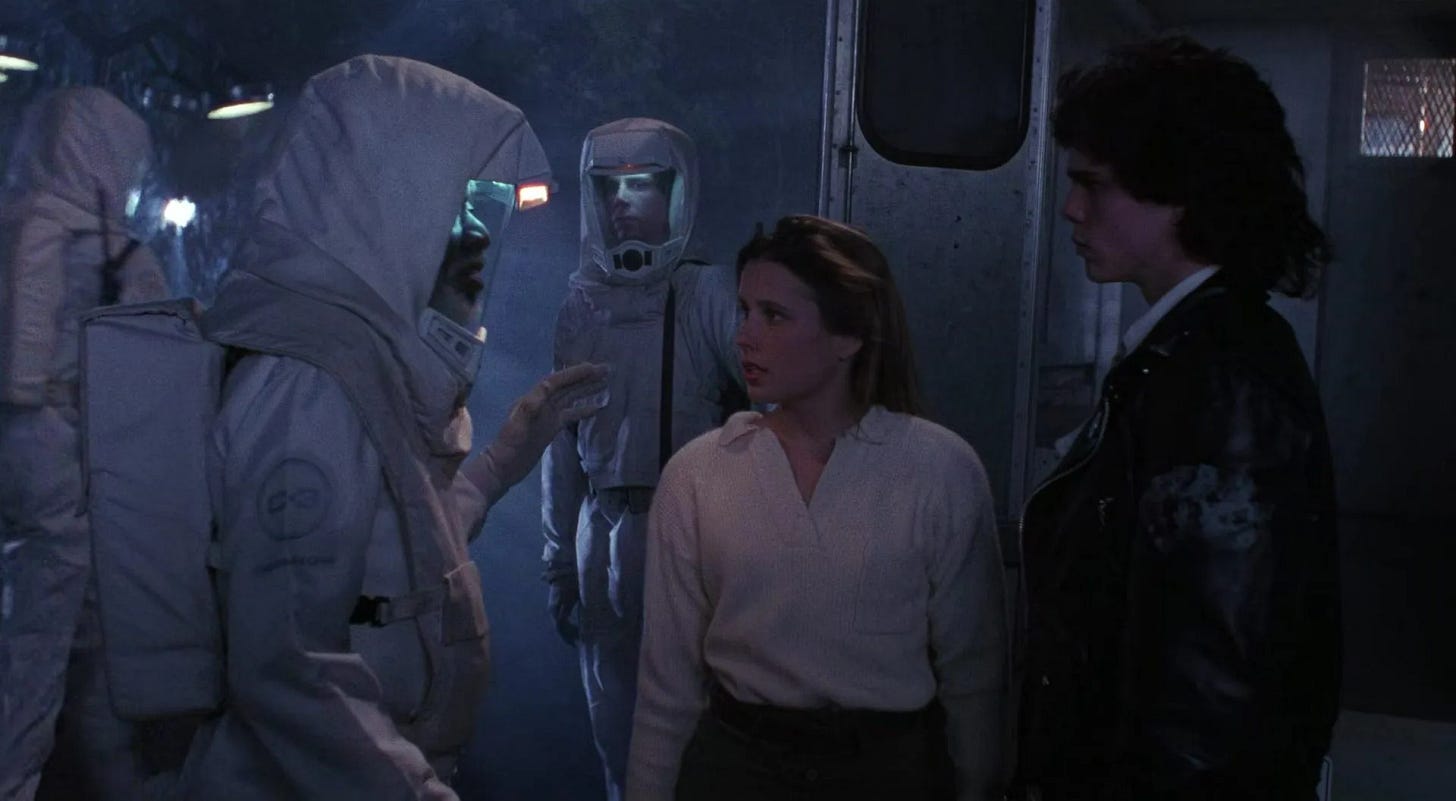

The casting (by Johanna Ray, who cast David Lynch’s projects from Blue Velvet onward) is good if not “very good.” Kevin Dillon, Shawnee Smith and Donovan Leitch are introduced with a dynamic that recalls a bit of Han Solo, Princess Leia and Luke Skywalker. Dillon–booking a part that Richard Greico was up for and Charlie Sheen, too prestigious for monster pictures after Platoon and Wall Street (1987), would’ve been perfect for–doesn’t have a romantic skin cell on him, but cast as a mullet-wearing miscreant with a contempt for authority, he brings that guy. Dillon isn’t playing the Steve McQueen part from the original, Shawnee Smith is and she’s a revelation. Like McQueen, Smith is heaven-sent for action movies, saying more with her face or posture than she needs to in dialogue, until she screams, doing so with power that’s a special effect in its own. Though stardom alluded her, Smith went on to play Jigsaw’s apprentice in five Saw movies (2004-2023), earning her a booth at horror conventions for life. Frank Darabont ascended to the greatest career heights, adapting and directing The Shawshank Redemption (1994), The Green Mile (1999), The Mist (2007) and writing and executive producing the debut season of AMC’s The Walking Dead. The monster remake he co-wrote with Russell has finesse, moving fast once the blob’s rampage begins, but taking care to introduce its characters and make us like most of them, a sacrifice many horror movies make to get to the gore. The Blob is chock full of virtually every practically built special effect shot in camera, which work in a well-directed tandem to make its monster both consistent, menacing and a real character.

Video rental category: Horror

Special interest: Movie Within A Movie