Something Wild

Jagged and wholly original screwball comedy/ road movie/ crime thriller

In the month of September, Video Days plays the sucker for women who lure us into a world of danger.

SOMETHING WILD (1986) is a road trip in which driver and passenger are making things up as they go, hitting the road with a quarter tank of gas, no change of clothes and an open container. The movie is exhilarating for those reasons and frustrating for the same reasons. Based on a screenplay written by a film school student learning to write and directed by a filmmaker relearning how to direct, neither give the viewer the reassurance we’re headed somewhere, but this is part of what makes the journey such a thrill.

Eric Max Frye was born and raised in Eugene, Oregon. His parents were lawyers, Frye’s mother the first woman to serve as judge of the Lane County Circuit Court and the first woman appointed to the U.S. District Court for Oregon. Her son spent a year attending Lewis & Clark College before dropping out. Interested in fine arts, painting in particular, Frye spent some time in Paris, and modeled in Austria. By 1981, he was in New York, living in the East Village and giving a career as a painter a go for a year or two before he was accepted to NYU’s Tisch School of the Arts. Not sure what he wanted to do, Frye had to take Dramatic Writing as a prerequisite and discovered an aptitude for screenwriting. Interning as a reader for a company that produced TV movies-of-the-week, Frye was emboldened by the poor quality of material coming in from literary agencies. The moment he graduated, Frye hopped a flight to Los Angeles and took with him the script he’d workshopped at NYU, a hybrid screwball comedy/ road movie/ crime thriller titled Cross Cut. Defying the experiences of most who came to L.A. with a script, within three months, Frye landed representation. Asked to name a director or directors he’d like to make his movie, Frye jumped to the head of the line by proposing Martin Scorsese or Jonathan Demme.

While Scorsese was finishing his latest picture A Night In Soho (released as After Hours in 1985), Demme was questioning whether he’d direct again. Born in Baldwin, New York, a suburban hamlet on Long Island, he’d grown up in nearby Rockville Center, where birdwatching was an early passion. At the age of 15, Demme’s father took a job as publicist for the luxury Fontainebleau Hotel, moving the family to Miami. Attending college at the University of Florida at Gainesville, Demme was perplexed by chemistry, making a career in veterinary medicine unlikely. Other than animals, Demme’s passion was the movies, and his bid with a high school friend named Buzz Kilman to bring a summer film series to Miami got the attention of the Coral Gables Times, which hired Demme and Kilman as arts and entertainment critics for the daily newspaper in November 1965. Demme’s father had become acquainted with a guest at the Fontainebleau, Joseph E. Levine, founder of Embassy Pictures. Demme shared some of his son’s film reviews with the producer, who sparked over a rave Jonathan had written for Levine’s production Zulu (1964). A college dropout, Demme was offered and accepted a job working in the Embassy Pictures publicity department in New York.

In the fall of 1967, Demme had moved into publicity for what was at that time one of the major studios: United Artists. This introduced him to his wife Evelyn Purcell, the magazine publicity contact for Eon Productions, producers of the James Bond films. The couple moved to London, where Demme was recommended by his old boss for the job no one really wanted, unit publicist for a WWI flying ace picture shooting in Ireland, Richthofen and Brown (1971). The director was founder of New World Pictures, Roger Corman, whose reputation for giving anyone young and hungry an opportunity in Hollywood was becoming legendary. Demme had journeyed to Ireland with a friend, a commercial director named Joe Viola, and Corman asked Demme if he was up for producing a movie for him, which Viola would direct, from a script the duo would write. Demme & Viola concocted a biker gang version of Rashomon (1950) they ultimately titled Angels Hard As They Come (1971), shot in Los Angeles and Yuma, Arizona in three weeks for $125,000 with an unknown named Scott Glenn in the lead. This was followed by The Hot Box (1972), a women’s prison picture Demme co-wrote and (with his wife) produced in the Philippines, where Corman had a favorable production deal. Demme directed the second unit, enough for his boss to promote him to director. Demme’s on-the-job film school for Roger Corman would consist of directing three pictures: Caged Heat (1974), Crazy Mama (1975) starring recent Academy Award winner Cloris Leachman, and Fighting Mad (1976) with Peter Fonda in the lead.

Demme’s graduation from New World Pictures resulted in the best reviews of his career with Citizens Band (1977), an ensemble comedy written by Paul Brickman that under Demme’s direction, proceeded as if Robert Altman was directing Smokey and the Bandit (1977). Starring Paul Le Mat, the film did not draw an audience, but Paramount Pictures had enough faith to re-release it under a new title (Handle With Care) and marketing campaign, to similar results. Demme was next offered the best material of his career: the offbeat. loosely-based-on-a-true-story Melvin and Howard (1980), starring Paul Le Mat, Jason Robards as Howard Hughes and Mary Steenburgen (who won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress, along with Bo Goldman for Best Original Screenplay). Struggling to interest the major studios in the types of films he was interested in, Demme took the best job that came along, adapting screenwriter Nancy Dowd’s “Rosie the Riveter” comedy/ drama Swing Shift (1984). Demme assembled his strongest cast yet: Goldie Hawn, Kurt Russell, Ed Harris, Christine Lahti, Fred Ward, Holly Hunter.

Both Goldie Hawn and Warner Bros. disliked Demme’s cut of Swing Shift, which instead of remaining a vehicle for the star of Private Benjamin (1980) had evolved into an ensemble story about sisterhood. Hawn and Warner Bros. ordered rewrites and replaced Demme’s director of photography Tak Fujimoto for reshoots, which Demme muddled through without much in the way of new material or enthusiasm to improve it. He was focused on his next project, the independently financed Stop Making Sense (1984), a document of the Talking Heads’ 1983 concert tour to promote their 1983 LP Speaking In Tongues. Stop Making Sense would be hailed by many the greatest concert documentary ever made, accounting for Martin Scorsese’s The Last Waltz (1978) and Woodstock (1970), the latter of which Scorsese had worked on as an assistant director and assistant editor. But the experience of Swing Shift being taken from him and chopped to pieces had Demme questioning whether he wanted to direct any kind of motion picture again.

A year and a half after Swing Shift imploded, a gofer in Demme’s office named Ed Saxon read Cross Cut over the July 4th weekend of 1985 and recommended it to his higher-ups. Demme was struck by the originality of E. Max Frye’s script, which like his vision for Swing Shift, began as one kind of movie before shifting gears into another. The characters–a free spirited woman who picks up an affable Yuppie at a luncheonette in New York and starts driving south, their destination unknown–were different from the people in other movies Demme had seen. The script, which had come in out of the blue, just kept surprising him. Mike Medavoy, co-founder of Orion Pictures, was head of film production for the studio, which would finance and/or distribute fifteen pictures in 1986, including the thriller F/X, Hannah and Her Sisters (under a deal granting Woody Allen total autonomy over his films in the 1980s), the Rodney Dangerfield blockbuster Back To School and in a distribution deal with Hemdale Film Corporation, At Close Range, Hoosiers and the Academy Award winner for Best Picture and Best Director, Platoon.

Orion was the last remaining movie studio headquartered in New York, and though some in Hollywood considered its leadership elitist, Orion stuck to financing and distribution, allowing filmmakers they trusted the creative freedom to direct scripts Orion liked under a certain budget. One of these filmmakers was Jonathan Demme, who’d known Medavoy since the mid-seventies and would make four of his next five pictures for him, three at Orion and one at TriStar Pictures, where Medavoy landed as chairman in 1990. Producing Cross Cut with Demme was veteran New York unit production manager Kenneth Utt, who’d worked on Midnight Cowboy (1969) and The French Connection (1971). On his first read of the script, Demme pictured Melanie Griffith playing Audrey Hankel, aka Lulu, a fan of the fearless performance she’d given in Brian DePalma’s thriller Body Double (1984). Griffith was the first actor Demme offered the part. To play Lulu’s willing hostage Charles Driggs, Demme knew Kevin Kline and favored him for the role, which Orion endorsed while also suggesting Jeff Daniels, who they were familiar with, having bankrolled The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985), in which Woody Allen had replaced Michael Keaton with Daniels after filming was underway. A pairing of Griffith with Daniels clicked for Demme.

The third major role–Audrey’s sociopath ex-husband Ray, who derails the lovers’ weekend–went uncast for a while. For the audience to be intimidated by Ray, Demme kept waiting for an actor to intimidate him in his audition. Smarting from a bad experience she’d had with an actor on another film, Griffith had been given informal casting approval by Demme. To play her character’s ex, Griffith suggested a friend named Ray Liotta. An alumnus of the soap opera Another World, Liotta had scant screen credits to show for nearly five years in Los Angeles looking for work. He’d remained friends with a college pal from the University of Miami–actor Steven Bauer–who’d married Griffith in 1981. Prior to Body Double, Griffith was better known as the daughter of Tippi Hedren and had worked sporadically as an actor herself, mostly in television. She’d suggested Liotta join the acting class she belonged to, instructed by Harry Mastrogeorge, which Liotta would remain a student of for twelve years, even after he started booking film roles. A friend told him to give Griffith a call to see if she could get him an audition for Cross Cut. Casting directors Billy Hopkins and Risa Bramon had already considered and rejected Liotta, but with Griffith getting him through the door, Liotta so frightened Demme that he won the part, his film debut.

On a production budget of $7 million, Cross Cut commenced filming in March 1986. With nothing he really wanted to build on, Demme considered the project an opportunity to learn how to direct all over again. He did not storyboard his shots, and prior to the day of shooting, held no rehearsals, Demme preferring to let the actors work out how they were going to perform a scene once they arrived at the location, and while getting into their hair, makeup and wardrobe, Demme would work with director of photography Tak Fujimoto to determine where to put the camera and how to light the space. (The fight to the death between Charlie and Ray was shot largely with Daniels and Liotta performing their own stuntwork and blocked). Set mostly in Pennsylvania and Virginia, the film was shot largely in Tallahassee, Florida. The liquor store, the Apalachee Motor Lodge (where Lulu takes Charlie for their first romp), “Mom & Dad’s Italian Restaurant,” the Northland Motel (with local artist Jim Roche appearing as a yokel who gives Charlie a hangover remedy), Audrey’s childhood home (Florida actor Dana Preu playing her mother, “Peaches”) and Charlie’s house (scripted as being in Stony Brook, NY) were all filmed in the Sunshine State’s capitol city.

Buoyed by critical raves for what was now titled Something Wild, Orion staked a release date of November 7, 1986 in 914 U.S. theaters. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert gave the film two thumbs up. Siskel thought the picture very much in the tradition of a screwball comedy from the 1930s, despite its violent turn, with an added jolt of unpredictability that had him second-guessing what was about to happen. Ebert agreed, citing It Happened One Night (1934) with Claudette Colbert & Clark Gable: well made, funny, fast moving, with a director in Jonathan Demme who could do anything. Ebert did find the sexual interaction between Lulu and Charlie more interesting than the crime spree Something Wild shifted into. Confident audiences would embrace the film as critics had, Orion released Something Wild against three successful comedies, two in their fifth weekends of release (Jumpin’ Jack Flash and Peggy Sue Got Married) and the juggernaut of “Crocodile” Dundee, conquering the U.S. in its seventh weekend. Spiked with kinkiness and terror in an era when popular movies were noted for their wholesomeness (as the appeal of Mick Dundee was demonstrating), Something Wild defied categorization and proved a more difficult sell than Orion anticipated. It managed two weekends among the top ten grossing films in the country before the studio started pulling it from theaters.

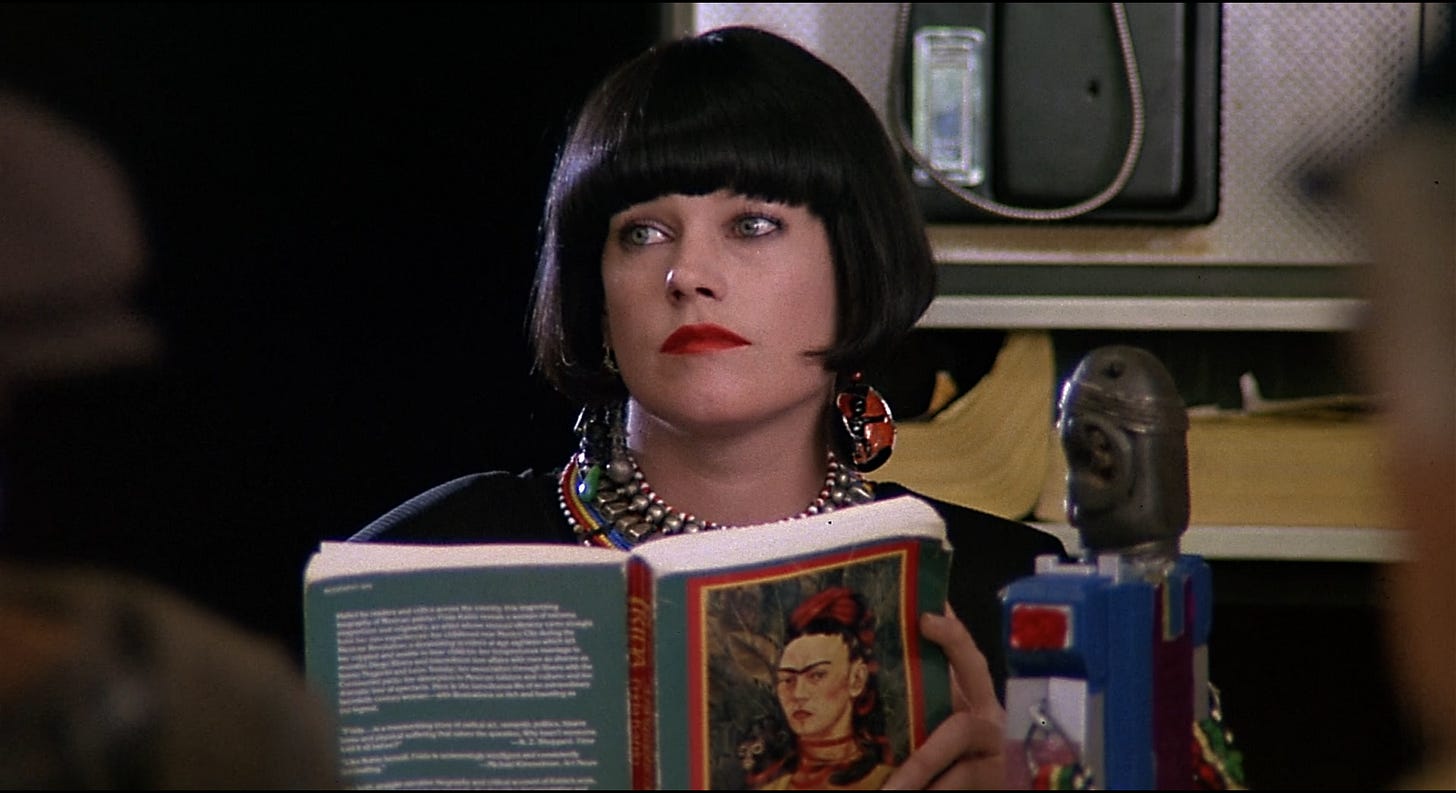

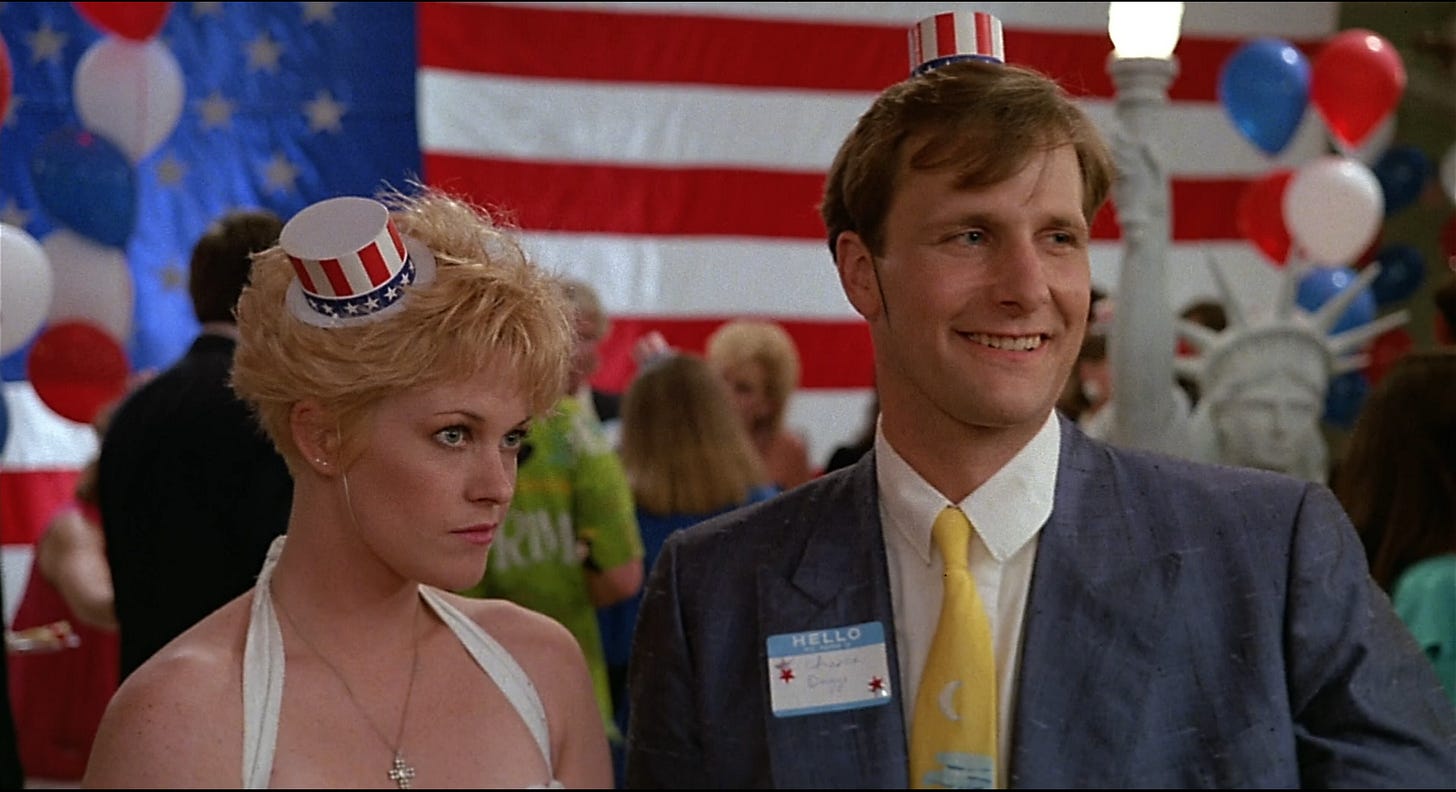

Watching Something Wild is like watching the build for a house of cards, a screenwriter and director going perilously higher under a paper thin foundation. E. Max Frye and Jonathan Demme test how much they can stack without the entire structure imploding, stopping one card short. Demme’s next picture for Orion, Married to the Mob (1988), would pile too many cards on top of a weak base and crumble. The reason Something Wild works is the couple at its core, Melanie Griffith and Jeff Daniels playing a hip, KCRW variation on the characters in a classic film noir. Rather than shadow and glamour, the picture is loaded with color and kitsch. Demme’s skills as a music supervisor are on point, painting Lulu with funky world music (“Wozani Mahipi” by The Mahotella Queens) and reggae (“Ooh! Aah!” by The Fabulous Five). Griffith’s early scenes are nutty and explosively funny. Donned in a Louise Brooks wig and swigging whiskey with wrists covered in bracelets, Griffith is not only sexy–squeaking like a girlish pinup whose image jumped off the siding of a WWII bomber–but is driven by pure id, sent by the gods to breathe impulsivity into the life of an investment banker, even if she has to open his lips with hers. As femme fatales go, Griffith plays one of the most alluring, her look by production/ costume designer Norma Moriceau (who dressed the Mad Max and “Crocodile” Dundee pictures). Jeff Daniels’ setting as a film actor is “wholesomeness”, and this is another picture he bounds through like a golden retriever. Rather than bring frenetic terrier energy as Kevin Kline might’ve, Daniels hangs his head out the window game to go anywhere Lulu wants him to, giving us permission.

Reaching for an antagonist, Something Wild swaps the sexual chemistry between Griffith and Daniels for the magnetism of Ray Liotta, who not only redirects the movie into a thriller, but takes over. Liotta is the joker’s wild, and Demme allows his character to bring the movie to a halt, Audrey and Charlie frozen just like we are, tensed to see what Ray does next. The movie gets by on its spirit, but the script doesn’t work exactly, not even the moment Lulu meets Charlie. Frye seems to think Lulu is cruising for an outlaw, but if that was true, she would’ve either stuck with her ex-husband, or picked up a stockbroker. What attracts her to Charlie isn’t that he steals from hard-working waitstaff for a thrill, but that he’s gentle, pliable and married, making him easier to control. If she’d seen Charlie pay the bill another diner dashed on, that would’ve suited her needs. Demme shorts Griffith and Daniels well-deserved screen time by indulging too many eccentric characters with absolutely no impact on the story, like reggae artist “Sister” Carol East, who drops in like a troubadour to break the fourth wall and sing “Wild Thing” over the end credits. Sacrificing a bit of free spiritedness to develop the relationship between Audrey and Charlie would have made the film less disposable and more rewatchable.

Video rental category: Romantic Comedy

Special interest: On the Road