Shadows and Fog

Sets and lighting crush characters and story in "philosophical comedy"

Standup comic/ actor/ writer/ director Woody Allen was born on November 30, 1935 in the Bronx, NY. To celebrate his 90th birthday, Video Days returns to his third decade of work this month with ten films from the master filmmaker.

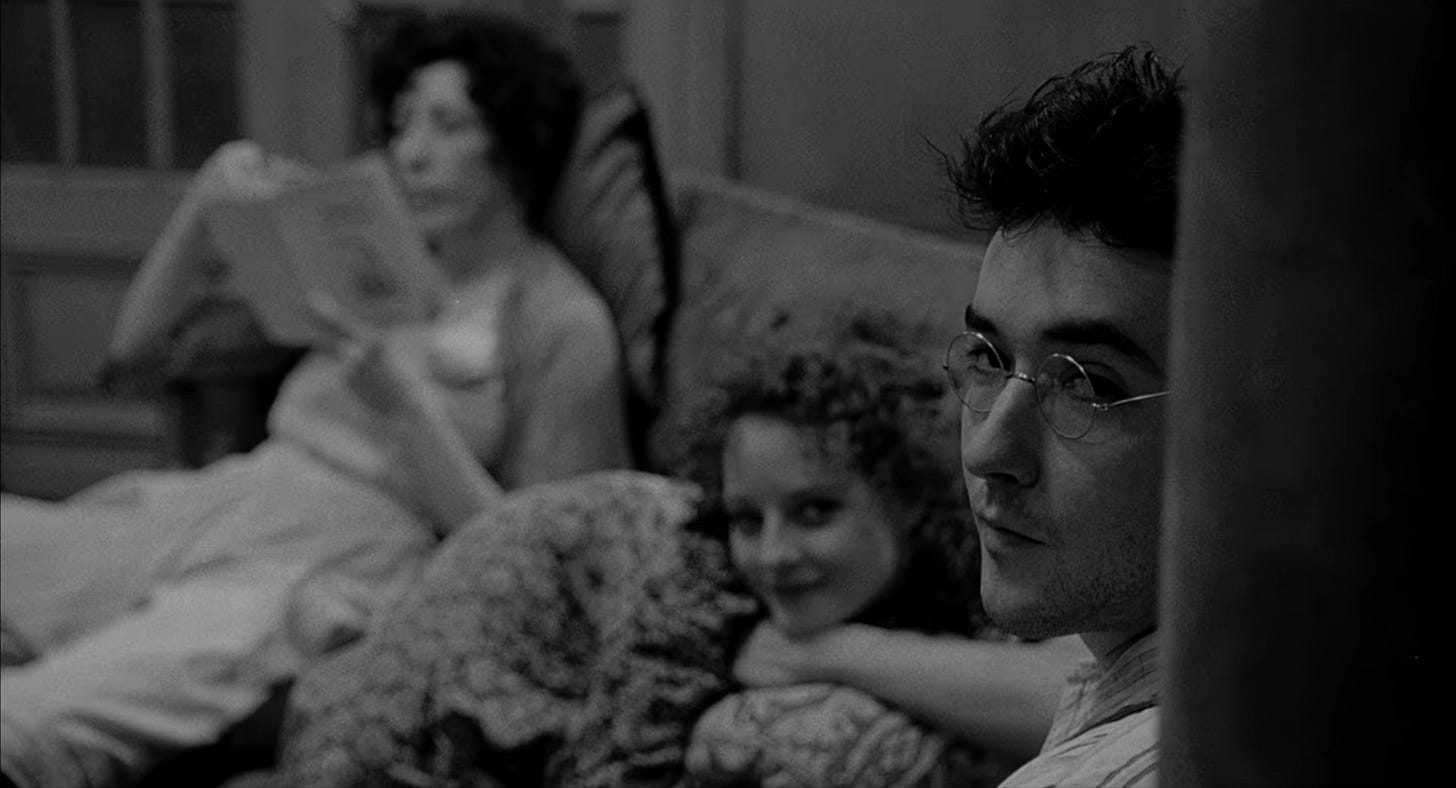

SHADOWS AND FOG (1992) is artifice with a comedy buried underneath, desperate to get out. Ostensibly set in Berlin during the Roaring Twenties, this star-studded non-event written, directed and starring Woody Allen takes its literary inspiration from The Trial by Franz Kafka, while its color palette and existential anxiety are indebted to the classic films of German Expressionism, namely Nosferatu (1922) and M (1931), which concerned the hunt for killers stalking the night. These were a major influence on the first monster movies Hollywood would produce in the 1930s and noirish crime pictures soon after, but Allen’s version settles for polite, stylistic homage without shaking the dust off the books or movies that inspire it.

Death was the title of a one-act play by Woody Allen, published in 1976 in his second collection of prose, Without Feathers. It was about a man named Kleinman awakened in the night by vigilantes who draft him into their hunt for a murderer they say is on the prowl. Forced to man a post on a street corner, Kleinman interacts with a doctor fascinated by the psychopathic mind. Kleinman is next kept company by a prostitute. They discuss the evening’s events, namely, the question of death. As the body count climbs and mobs face off against rival mobs, a clairvoyant employed to unmask the killer pins the murders on Kleinman. Embarking on what would be a script for his twenty-first film, Allen chose to expand the one-act play into a three-act screenplay. Instead of a contemporary American setting, the only environment appropriate for his Kafkaesque comedy was a European town in the 1920s. Allen expanded his story to include a traveling circus, in which a sword-swallower named Irmy leaves her lover, a clown, over his infidelity with a trapeze artist. Needing money or at least a place to stay the night, Irmy seeks refuge in a brothel. Eventually, Kleinman and Irmy cross paths in the night.

Moving forward under the working title Woody Allen ‘91, the setting of Allen’s next film dictated its style. Allen mimed the look that directors like F.W. Murnau or Fritz Lang had developed in Germany in the 1920s before heading to Hollywood, where Murnau segued from Nosferatu (1922) to Janet Gaynor in Sunrise (1927) for producer William Fox, and Lang fled the Nazi regime for Southern California in 1935, where the director of Metropolis (1927) and M (1931) reeled off crime pictures with big stars, Fury (1936) starring Sylvia Sidney and Spencer Tracy, Ministry of Fear (1944) with Ray Milland, and Scarlet Street (1945) starring Edward G. Robinson, to name a few. (Between the directors, Allen would favor the more romantic look and feel of Murnau). Though he had directed three films shot in black-and-white–Manhattan (1979), Stardust Memories (1980), Broadway Danny Rose (1984)--they’d been contemporary American stories, and Allen’s next would be his first in monochrome with director of photography Carlo Di Palma.

For the art design, Allen started by thinking in terms of a play, with minimalist sets in which windows or doors would be painted instead of built. Settling for a movie in such a limited dimensions didn’t appeal to Allen, and his production designer Santo Loquasto was tasked with designing and building more elaborate sets, to be shot at Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens, New York, where Allen had filmed September (1987) in its entirety and some interiors for his previous film, Alice (1990). The streets, carnival fairground and a bridge would be constructed on a set, as would interiors for the townhouses, morgue and brothel. The 26,000 square foot set–lighting or fog effects concealing that some of it was reused in other shots–was heralded as the biggest set ever constructed in the New York area. It was larger than the roughly 18,130 square foot apartment building courtyard for Rear Window (1954) built on a soundstage at Paramount Studios in Hollywood, but dwarfed by the 174,240 square feet of space on the RKO Ranch in Encino, where the town of Bedford Falls was built for It’s A Wonderful Life (1946).

Production on Woody Allen ‘91 commenced in November 1990 under the largest budget Allen had been afforded up to that point: $19 million. As a comparison, the budget Allen’s financier and distributor Orion Pictures had announced for The Silence of the Lambs (1991) was also $19 million, while the studio had earmarked The Addams Family (1991) at $25 million. Allen took the part of Kleinman, and as Irmy, his partner Mia Farrow, in their eleventh consecutive picture together. The all-star cast included John Malkovich as Clown, Madonna (then in her sex symbol phase, between playing a siren in Dick Tracy and publishing a coffee table book, Sex) as the trapeze artist, Lily Tomlin, Jodie Foster and Kathy Bates as prostitutes, and John Cusack as the john who Irmy entertains. Donald Pleasence was cast as the doctor studying the psychotic mind, picking up where he’d left off in Halloween (1978). Wallace Shawn and Julie Kavner, regulars in Woody Allen’s comedies, appeared in a scene each opposite the filmmaker, while Kurtwood Smith, David Ogden Stiers, James Rebhorn, Victor Argo and Daniel Von Bargen played mob members. Working for Woody Allen carried such prestige that when Howard Hesseman exited the ABC sitcom Head of the Class in 1990, the explanation that viewers were given for the departure of Hesseman’s character, Mr. Moore, was that he’d been offered a role in a Woody Allen film. That gig would’ve been Shadows and Fog, the title Allen arrived on for what Orion referred to as “a philosophical comedy”.

For nine consecutive years, Woody Allen had written and directed at least one movie per year, making up for missing 1981 with two films in 1987: Radio Days and September. Shadows and Fog was on track for a late 1991 release along with The Addams Family, but the extent of Orion’s financial troubles became evident when they sold domestic distribution rights for the latter to Paramount Pictures in order to keep the studio solvent. In May, Orion ceased interest payments on their debt. After ten years of sustained commercial and critical success, 1989 has been a terrible year for the studio. Farewell to the King, Speed Zone, Great Balls of Fire!, Rude Awakening, The Package, Valmont and She Devil were all shunned by audiences. A blockbuster late the following year (Dances With Wolves) and another three months later (The Silence of the Lambs) failed to satisfy the studio’s debts and in December 1991, Orion filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection. With the cost of prints and advertising between $10-15 million per picture, twelve films in Orion’s pipeline sat without a release. These included Article 99 with Ray Liotta and Kiefer Sutherland, Love Field starring Michelle Pfeiffer, and Woody Allen’s latest.

Shadows and Fog held its premiere in New York in December 1991, but general audiences wouldn’t get a look at the film until February 1992 when it opened in France. This was Allen’s first movie to open in Europe before it did in the U.S. Several of his films not only set in the Continent but filmed there–Match Point (2005), Cassandra’s Dream (2007), Midnight In Paris (2011), To Rome with Love (2012), Rifkin’s Festival (2020)--would follow a similar release. On March 20, 1992–a week after Orion released Article 99 on 1,263 screens--Shadows and Fog opened on 288 screens. It failed to find a spot among the top ten grossing films, and as the studio dissolved and its library was sold off, Shadows and Fog would be the last of eleven films Allen made at Orion. Critical response was negative. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert turned two thumbs down in a hurry. Siskel introduced it as “ … a most disappointing film from one of our great filmmakers, who seems to have really lost his way this time, making a film that’s more about art direction than any kind of story.” Ebert retorted, “It is a major disappointment. It’s 86 minutes long and it could be 20 minutes shorter with no problem at all. There’s nothing here.” Siskel would remember Shadows and Fog when compiling his list of the worst films of 1992 for At The Movies. In print, Michael MacCambridge of the Austin American Statesman offered an opposing view: “None of this works as an actual noirish thriller because Woody is so busy winking. In many ways, the film is similar to his old genre send-ups such as Play It Again, Sam (1972) and Take the Money and Run (1969), except this one has a substantial religious undertone to it.”

Expanding a one-act play he’d published at a younger age makes it hard to ignore that Woody Allen was stuck in a creative drought in 1991. Due to its color palette and the sinister air of German Expressionism it models, Shadows and Fog immediately brings to mind a much better genre send-up: Young Frankenstein (1974). A younger Woody Allen might’ve ripped and run through horror films before Gene Wilder & Mel Brooks, choosing instead to rib movies he had an affinity for, namely prison documentaries in Take the Money and Run and Humphrey Bogart pictures in Play It Again, Sam, as well as science fiction with Sleeper (1973). Shadows and Fog is awfully diffuse and compared to Allen’s work in the early seventies, that’s saying something. The film lacks focus. Allen doesn’t settle on a genre to poke fun at or a filmmaker to pay tribute to. He cuts and pastes the monster from Nosferatu, a wrongfully accused man in M, philosophy from an Ingmar Bergman movie and a circus troupe from a Federico Fellini film. Even viewers without Film 101 who don’t know G.W. Pabst from Pabst Blue Ribbon can detect that this comedy is composed of leftovers.

Franz Kafka (1883-1924) had a great year in 1991. Steven Soderbergh’s sophomore feature Kafka (1991) starred Jeremy Irons in an original blend of biography and noirish thriller. David Cronenberg’s adaptation of William S. Burroughs’ novel Naked Lunch (1991) drew on some of Kafka’s work. Oliver Stone cited the author in the closing arguments of Jim Garrison (Kevin Costner) in JFK (1991). Then there’s this Kafkaesque comedy by Woody Allen. The most exciting moments in Shadows and Fog are those that economize Allen as a director and push him into the pacing of a horror film, with a medical examiner played by John Carpenter regular Donald Pleasence stalked in his lab by the killer (Michael Kirby) and realizing that his study of evil is no longer academic. Allen’s writing finds a home during the brothel scenes, being neither the first or the last of his films to play a comedy of errors between a prostitute and her clientele. Transplanting characters with American accents to an amusement park version of Germany in the 1920s relegates Shadows and Fog to an exercise that relies heavily on lighting and not at all on character or story. Mia Farrow appears to be going through the motions playing a circus performer, or directed to play the most despondent circus performer ever (Winona Ryder would’ve lit up the screen, while Madonna, who was the circus performer for Generation X, wouldn’t have been a bad idea in the part). John Malkovich might’ve made a compelling killer–with a European accent to suit–but is too brutish for a comedy. Kate Nelligan and Fred Gwynne, incapable of giving bad performances, might be missed with a strong sneeze. The most compelling mystery of the film is why Nelligan and Gwynne aren’t in more of it.

Woody’s cast (from most to least screen time): Woody Allen, Mia Farrow, John Malkovich, John Cusack, Lily Tomlin, Donald Pleasence, Julie Kavner, Wallace Shawn, Kathy Bates, Jodie Foster, Kurtwood Smith, Madonna, Kenneth Mars, Camille Saviola, Philip Bosco, David Ogden Stiers, James Rebhorn, Victor Argo, Daniel Von Bargen, Kate Nelligan, Josef Sommer, Fred Gwynne, John C. Reilly, William H. Macy

Woody’s opening credits music: “The Cannon Song, From Little Threepenny Music,” by Kurt Weill, performed by the London Sinfonietta (1967)

Woody’s closing credits music: “Moritat From The Three Penny Opera,” by Kurt Weill & Bertolt Brecht, performed by Berlin Staatsoper (1931) and “When Day Is Done,” Jack Hylton and His Orchestra (1927)

Video rental category: Comedy

Special interest: 24-Hour Time Frame