September

Woody Allen's chamber piece = audio/visual marvel + strained writing

Standup comic/ actor/ writer/ director Woody Allen was born on November 30, 1935 in the Bronx, NY. To celebrate his 90th birthday, Video Days returns to his third decade of work this month with ten films from the master filmmaker.

SEPTEMBER (1987) would qualify for study in film schools if it wasn’t quite so tedious to watch. Written and directed, but not starring, Woody Allen, this chamber piece is set entirely in a house in the countryside, and is staged more like a play than any film Allen would ever attempt. It fluctuates between emotional complexity and soap opera, with much of its drama spoken bluntly at the viewer. It is pedestrian in the best possible sense, utilizing the tools at a filmmaker’s disposal to tell a story without burning very much money.

Woody Allen had been mulling a story about a shared trauma, not one depicted on camera, but an event that has affected two characters differently, one devastated by it, and the other seemingly unaffected. His partner Mia Farrow owned a home in Connecticut, where she would drag Allen and he’d try his best to enjoy country living. Allen would elaborate to the New York Times in 1987. “One day we were strolling around her place and she said, ‘This would make a great setting for a little Russian play or something. It’s just so perfect. It would be fun to shoot up here. The kids would love it and you would have something to do all the time.’ And I thought, what a Chekhovian atmosphere this is. It’s a house on many acres, isolated by itself on a little piece of water. There are trees and a field here and a swing there. It suggested to me right away the kind of stories of Turgenev and Chekhov, which have a certain amount of comedy in them. It’s not real comedy but, I guess, comedy of desperation or anxiety.” Basking in the success of what many considered Allen’s best picture to date, the Academy Award-winning romantic comedy Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), the filmmaker felt pulled toward making smaller dramas like Interiors (1978), which he’d followed his previous critical and commercial smash Annie Hall (1977) with, and certainly had the prestige to make.

Proceeding under the title Woody Allen Untitled ‘86, his screenplay concerned a woman named Lane recovering from an overdose–deliberate or accidental–at the family home in Vermont, where her mother Diane, a show business legend, arrives for a visit before summer’s end with her husband Lloyd, a physicist. Also orbiting Lane is her friend Stephanie, who has begged off her husband and children for a summer in the country to recoup as well. Lane’s neighbor Howard, a widowed French professor twenty years her senior, is in love with Lane and saddened to learn she’s selling the house, while Lane covets a copywriter named Peter who’s renting her guest cottage to write a novel. Drawing from the Hollywood true crime in which Lana Turner’s abusive boyfriend, hoodlum Johnny Stompanato, was stabbed to death by Turner’s fourteen-year-old daughter Cheryl Crane in what the coroner ruled as self defense, Lane never recovered emotionally after surviving a similar ordeal as a child, while her dynamic mother preaches not looking back.

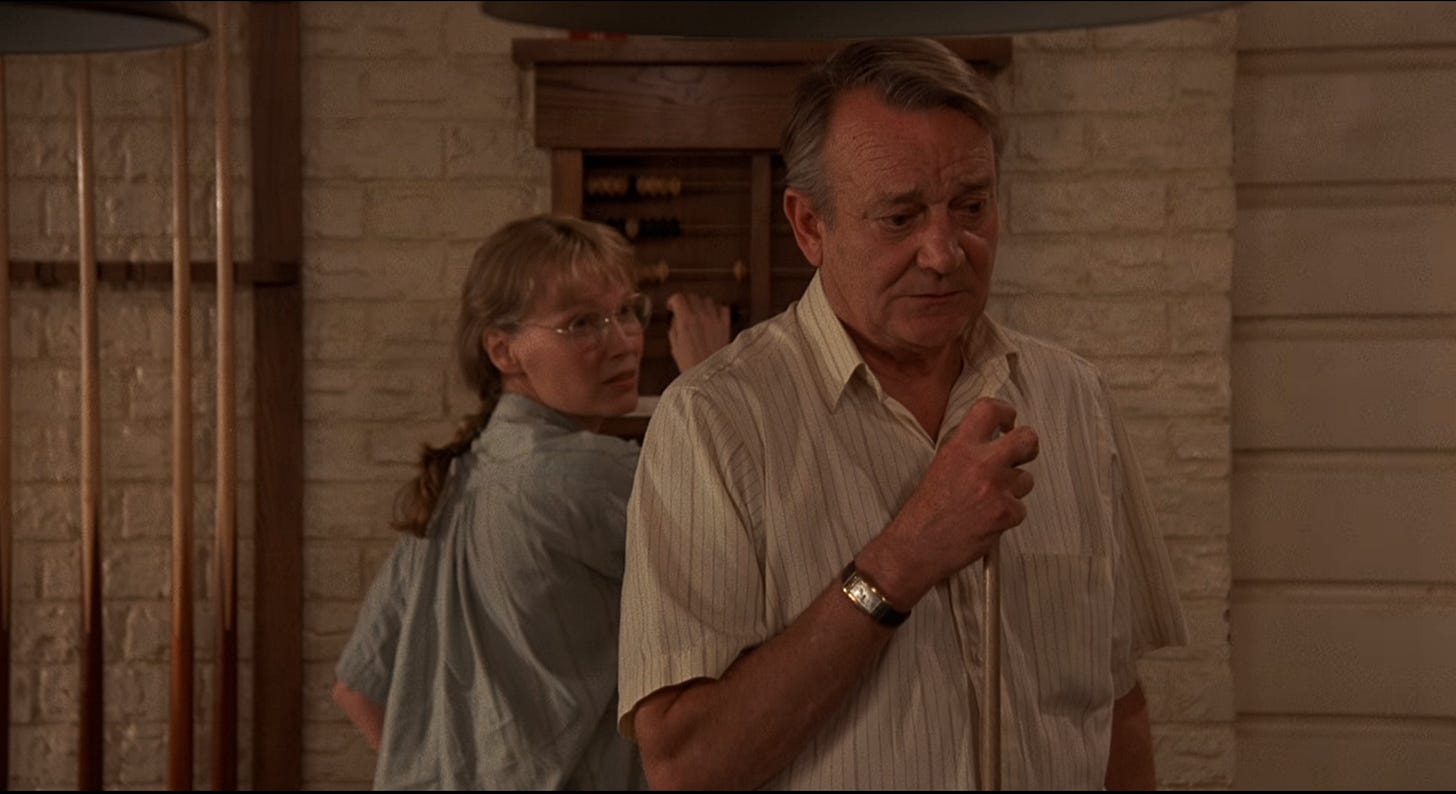

By the time Allen was ready to begin production on his seventeenth film, in late October 1986, temperatures would begin to drop, lending the picture a wintry look and feel that did not appeal to him. Allen preferred a melancholy, end-of-summer mood, so production designer Santo Loquasto constructed sets at Kaufman Astoria Studios in Queens, New York, where the picture would be shot in its entirety. Allen had written his female characters with three actors in mind, all of whom accepted their roles. Mia Farrow and Dianne Wiest were cast as Lane and Stephanie, respectively, with another cast member of Hannah and Her Sisters, Farrow’s mother Maureen O’Sullivan, the screen star of the 1930s and ‘40s, returning to play mother to Farrow’s character again. Denholm Elliott was cast as Diane’s husband Lloyd, Charles Durning as the neighbor Howard, and completing the ensemble, Christopher Walken as Peter. Loquasto’s art design called for simulating the outdoors with trees outside the windows, and while Allen conceded the greens looked fine on film, they gave the space an artificial feeling. The decision was made to rely on lighting and sound to suggest summertime, with a storm knocking out electricity on the characters in the second act and the white noise of the cicadas present throughout.

Woody Allen credited Christopher Walken as being one of his favorite actors, having cast him in Annie Hall as the title character’s spooky brother, Duane. After a few days of shooting on Allen’s latest, Walken announced he was dropping out of the production. In his 2020 memoir Apropos of Nothing, Allen would write that the issue was never Walken’s performance, but that the writer/ director and lead actor “couldn’t get copacetic on what to do.” They parted cordially and agreed to work together on something else. Sam Shepard–the playwright/ stage director who’d grown up in Southern California and as an actor, cultivated a quiet, rugged persona–was named as Walken’s replacement. Shepard, working with Allen for the first time, struggled with the screenwriter’s dialogue to the extent he requested and received a runway to rework some of it. Viewing his assembly with his longtime editor Susan E. Morse, Allen was more despondent than usual, dissatisfied with most of what he’d written and directed. “When I saw my first version, I saw many mistakes and character things I could do better. I didn’t need certain speeches and certain things needed to be said. This happened thirty times, in all the acts.”

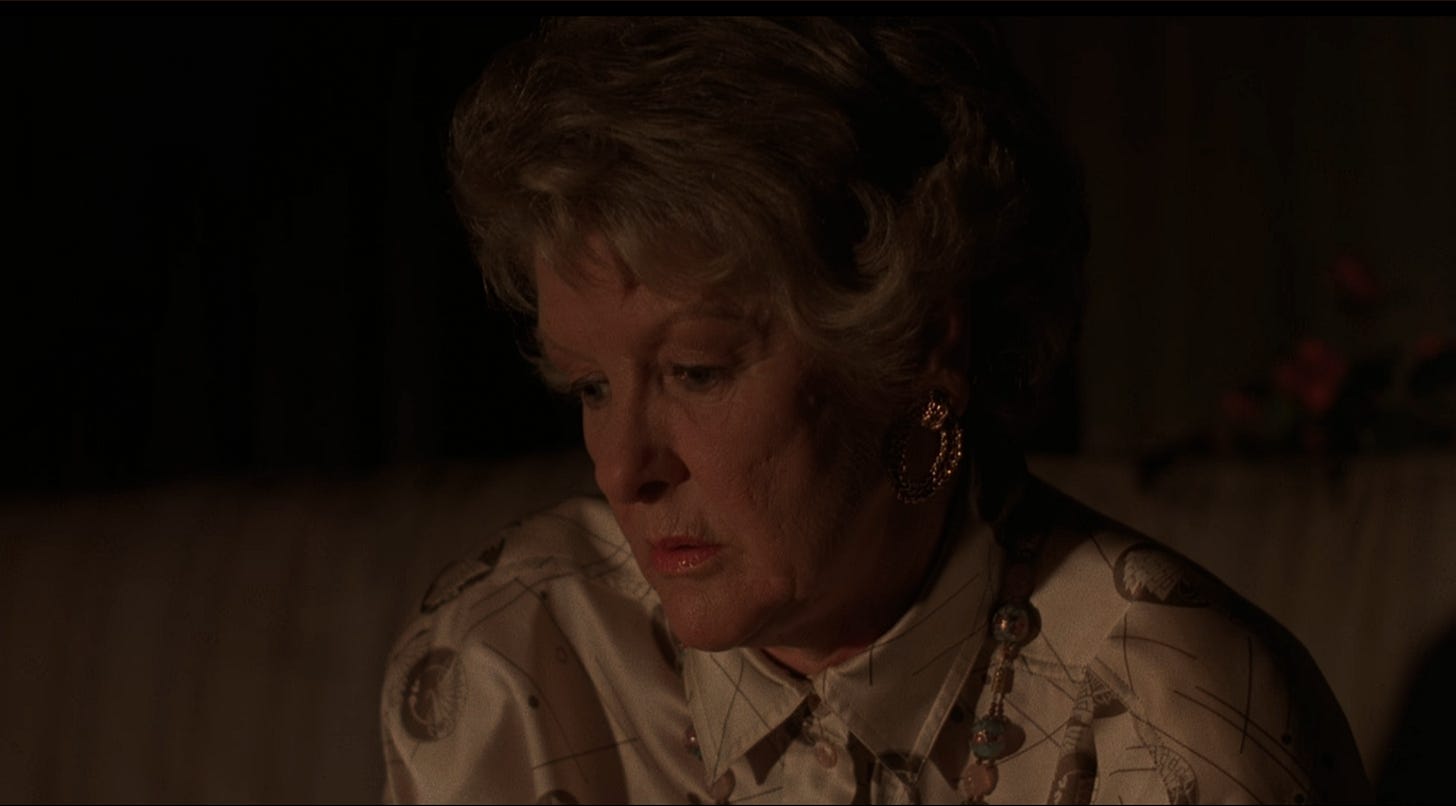

Allen considered an assembly a rough draft and had written and shot new material for several of his films after seeing them cut together, namely his most successful, Annie Hall and Hannah and Her Sisters. Having made Woody Allen Untitled ‘86 entirely on a set that was still standing, Allen assured his financier and distributor Orion Pictures that he could complete necessary reshoots in four weeks, adhering to the $10 million production budget he’d been allotted, which had baked in additional filming. Farrow and Wiest were available, but Charles Durning and Sam Shepard had commitments that made their participation impossible. In addition to recasting their roles, one of Allen’s primary concerns about his assembly had been the performance of Maureen O’Sullivan, who’d been hospitalized with pneumonia prior to filming and whose gifts as a raconteur had not translated to film. In his memoir, Allen would go as far to write, “She was just bad in the role.” Allen would be relieved of having to replace his partner’s mother when O’Sullivan’s health prohibited her from participating in the reshoots. Stage and television stalwart Elaine Stritch agreed to replace O’Sullivan, a change that made her character more assertive. Jack Warden was cast as her husband, while Denholm Elliott slid into the role of Howard. With fixes to his script, Allen considered recasting Christopher Walken as Peter, but the actor had another job lined up, shooting a geopolitical thriller in Israel titled Deadline (1987). Sam Waterston, who’d worked with Allen on Interiors and Hannah and Her Sisters, accepted the role.

Reshoots commenced in late February 1987 on what Allen would title September, settling as he often did, late in production. Orion opened the picture in limited release on December 18 on 15 screens. Even if the new Woody Allen film had been a comedy, it would’ve struggled for attention in a much more crowded field than Hannah and Her Sisters had debuted against. Eddie Murphy: Raw (1,391 screens), *batteries not included (1,328) and Overboard (1,126) opened the same day, alongside an unmitigated disaster, Bill Cosby in Leonard Part 6 (1,142), while another awards contender in Broadcast News (7 screens) opened in limited release, followed the next weekend by Good Morning, Vietnam (on 4 screens). Not surprisingly considering its content and form, September was ignored by audiences, but in his 2023 article “A neurotic half-century: every Woody Allen film, ranked,” John Hansen of Reviews from My Couch notched September at #16 out of 55 titles. “Allen churned out this small gem amid perhaps the busiest time of his career–Radio Days came out the same year and he shot another version of September in its entirety, only to be unhappy with it and try again … But it’s perhaps the most outdoorsy indoor movie ever, as characters comment on the Vermont weather and the stars. It’s hard to pick the best among the six outstanding performers whose characters fret about love, life, legacy and sanity.”

Woody Allen and his frequent collaborators–director of photography Carlo Di Palma, production designer Santo Loquasto, editor Susan E. Morse–wield magnificent sleight of hand throughout the 82-minute running time of September, crafting what was drawn up as a chamber piece, with a small cast and one location, into a film that looks and feels cinematic. Aspiring filmmakers could learn a lot about the toolbox available to them and how to use it from a picture that’s low if not micro-budgeted. Without exterior photography, the sound design gives the film an added dimension. In addition to summer insects and an August storm, Allen plants Dianne Wiest’s character at a piano where she plays tunes that pipe through the house over the twenty-four hours it takes place. These include “What’ll I Do,” “I’m Confessin’ (That I Love You),” and “On A Slow Boat To China,” the latter being a favorite of Allen’s that he plays over the opening credits. Doubling for Wiest was Bernie Leighton, a session pianist who recorded with Charlie Parker, James Moody and Cal Tjader, and toured with many other jazz greats. Whereas most of Allen’s films lit by Di Palma settle for a consistently burnt or crisp look, as if conjuring autumn in New York, the lighting in September is sultry, and combined with the sound, is a lovely film to look at and listen to.

While September is resplendent in its look and feel, its weakness is Allen’s purple screenplay. The atmosphere may resemble a Chekhov short story come to life, but the story plays out like All My Children, with characters dishing about characters in the other room, like they would in a soap opera. For a two-level house with only so much space under its roof, the six characters have an inordinate amount of time alone to trade secrets about each other, or conduct their private affairs. That Allen has no intention of dramatizing the lurid Lana Turner/ Cheryl Crane incident, like an episode of Law & Order would, is a given (ironically, Sam Waterston and Dianne Wiest would ultimately join the series as regulars, and Elaine Stritch would win a Primetime Emmy in 1993 for her guest appearance as a defense attorney). Dialogue drives the story, as it would a play, but Allen is so focused on what his characters are saying that he neglects what they’re doing. Other than vinyl records being played, nothing happens. Wiest and Stritch are rewarded with the richest characters–one afraid of opening up, the other too eager to do just that–and give award-worthy performances stirring with feminine energy. Denholm Elliott could enrich a reading of a parking ticket, and as always, is a pleasure to watch perform. September has style, but not quite enough substance to make it rewatchable.

Woody’s cast (from most to least screen time): Mia Farrow, Sam Waterston, Dianne Wiest, Elaine Stritch, Jack Warden, Denholm Elliott

Woody’s opening credits music: “On A Slow Boat To China,” Bernie Leighton (1987)

Woody’s closing credits music: “My Ideal,” The Art Tatum-Ben Webster Quartet (1956)

Video rental category: Drama

Special interest: 24-Hour-Time-Frame