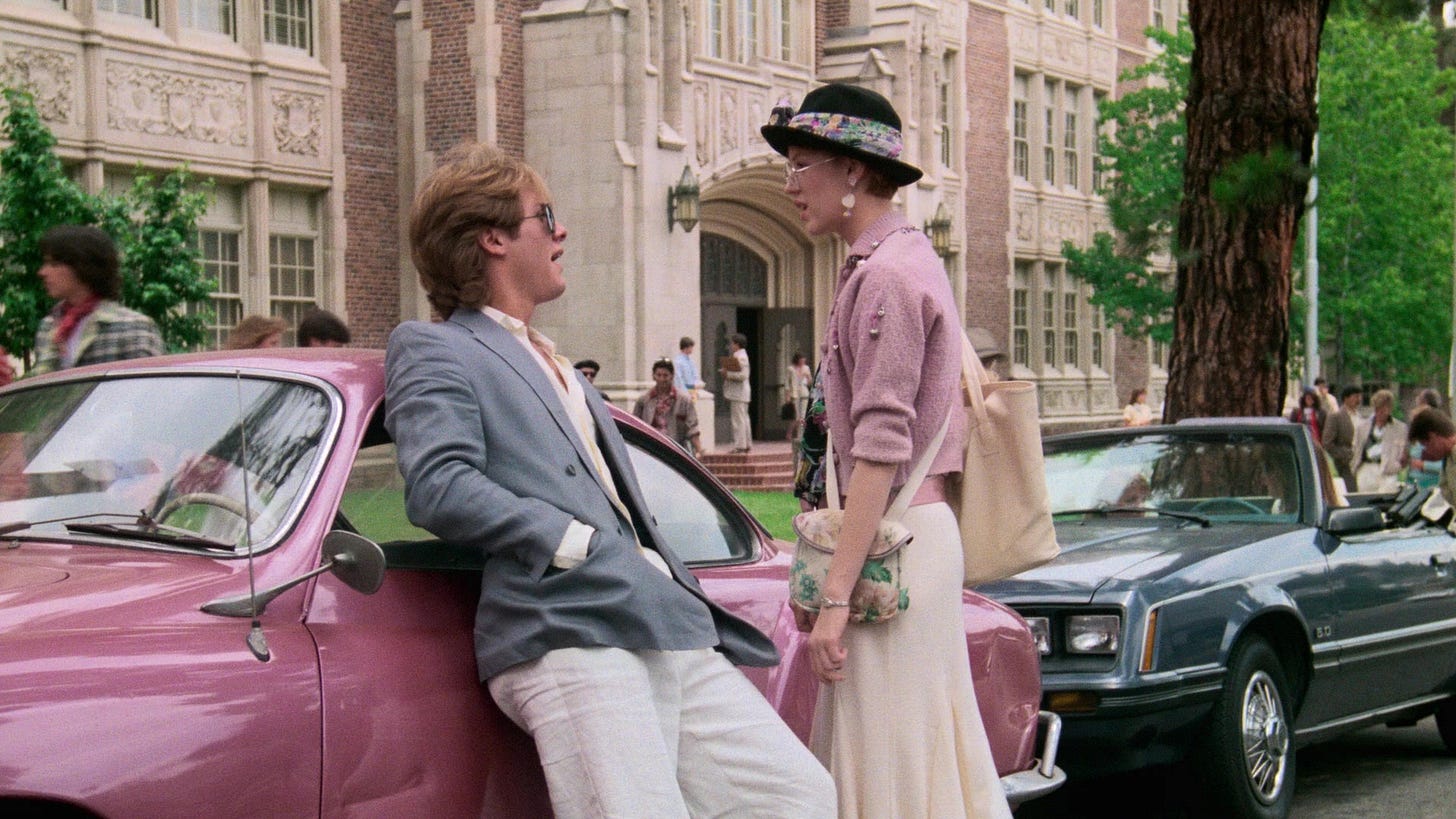

Pretty In Pink

Bumpy Valley Girl remake sticks its landing

The late writer/ director/ producer John Hughes was born February 18, 1950 in Lansing, Michigan. He’d be celebrating his 75th birthday this month. Video Days kicks off its inaugural month with a retrospective of ten of the filmmaker’s pictures.

PRETTY IN PINK (1986) does nothing that Valley Girl (1983) doesn’t do better, in some cases, remarkably better. It’s a watchable drama by virtue of the same timeless plot–a high school couple from opposite worlds fall in and out and back in love–but despite the talent behind and in front of the camera having more experience, as well as support from a major studio, it’s an inferior remake.

By the mid-eighties, filmmaker John Hughes had concluded that while he could write four or five screenplays in nine months–his ability to crank out the first draft of a new comedy in mere days was not a myth–he could only direct one in the same amount of time. As a writer/producer, Hughes started looking for directors to adapt his surplus work. He reached out to Howard Deutch, formerly senior partner in the marketing firm of Kanew-Manger-Deutch, which specialized in movie trailers. The New York company had not only cut trailers for Sixteen Candles (1984) and The Breakfast Club (1985), but at the request of one of the producers of Rumble Fish (1983), Deutch became a music video director, cutting his teeth with Stewart Copeland (“Don’t Box Me In”). This led to Deutch directing music videos for Billy Joel (“Keeping the Faith”), Billy Idol (“Flesh For Fantasy”) and to promote Sixteen Candles, Annie Golden (“Hang Up the Phone”). Hughes sent Deutch two scripts. The New Kid was a broad comedy and Pretty In Pink a cross-cultural romance.

Deutch responded to the latter, which Hughes had written for Molly Ringwald over one week in September 1983 after they’d wrapped Sixteen Candles. Taking its title from the New Wave single by The Psychedelic Furs, Pretty In Pink would be the first project from Hughes under his new three-year deal with Paramount Pictures, and though studio president Dawn Steel lobbied him to hire a female director, Hughes insisted on Deutch to make his feature film debut. Taking an executive producer credit with Michael Chinich, Hughes hired Lauren Shuler, who’d encouraged him while he was writing for National Lampoon magazine and had since produced Ladyhawke (1985) and St. Elmo’s Fire (1985), to serve as line producer. Hughes had penciled in Anthony Michael Hall to reunite with Ringwald in the cast, playing another misfit who this time, would win the heart of her character, a fashion aficionado making her own dress for prom and hoping a sensitive “richie” from the right side of the tracks will ask her. When Hall declined, Robert Downey Jr. was seriously considered before Jon Cryer was cast as the misfit. Lobbying for an actor she felt some romantic chemistry with, Ringwald succeeded in Andrew McCarthy being offered the role of the richie.

Written to take place in the Chicago area, Deutch did not share Hughes’ connection to or familiarity with the city or its suburbs. Shooting commenced in September 1985 in the Los Angeles area instead. Marshall High School in Los Feliz and John Burroughs Middle School in Hancock Park stood in for Andie, Duckie and Blane’s school. Scenes in and around Andie’s house were shot in South Pasadena and “Trax Record Store” was filmed at the 3rd Street Promenade in Santa Monica, in a storefront which up to 2019 was the site of a Cafe Crêpe. In spite of the ending to Hughes' script, Ringwald played Andie’s relationship with Duckie as if he were perhaps a gay friend, with zero romantic interest in him. When put before a test audience, the film’s original ending–Andie goes to the prom alone, is again ignored by Blane and is rescued by Duckie, who she realizes has been there for her all along–was audibly rejected. A majority of women wanted Andie to end up with the boy she liked.

Hughes, who’d been told by film critic Gene Siskel that his review of The Breakfast Club would’ve been four stars if Anthony Michael Hall’s character had ended up with Ringwald’s, acknowledged that this was not what the audience wanted. Hughes hit upon the idea of Blane also attending the prom solo, allowing Andie to seize her opportunity with him and Duckie to sacrifice himself so his friend could be happy. Paramount agreed to one day of reshooting, though not at the Biltmore Hotel where the prom had been shot, but on a sound stage. Andrew McCarthy had shaved his head for a play and a Blane-like wig was improvised for him to wear. When the new ending was tested the same evening as the original ending, the audience scored the former better. Opening in the U.S. on 827 screens in February 1986, Pretty In Pink was the #1 movie in the country its first two weekends. Expanding to 1,117 screens, it remained in the top ten grossing films for ten weeks.

Basking in another hit, Hughes was candid about reshooting the ending of Pretty In Pink, and when another Paramount picture, Fatal Attraction (1987), had a middling performance at test screenings, its ending was rewritten and reshot, to phenomenal commercial success. By the time Robert Atlman went into production on a satire of the film industry titled The Player (1992), its climax skewered Hollywood’s tendency to put a happy ending on any movie if the audience demanded it. Among the problems with Pretty In Pink, its ending is not one of them. Despite the efforts of Hughes and Deutch to make a movie where the princess chooses the frog, as well as strikes a feminist blow to hypergamy–which postulates that women’s attraction to men gazes up the socioeconomic scale, never down–Andie isn’t the one with identity issues. She wants to create, to stick by a man she chooses (unlike her absentee mother) and to upgrade her postal code. Duckie, on the other hand, as suggested by both the material and Cryer’s performance, is struggling with his sexuality. The ending is the first time he’s put Andie’s needs above his own, hardly the behavior of a soulmate. The “happy” ending the audience dictated is the one the movie sets up: Andie gets her man and Duckie starts paying attention to his own development.

Pretty In Pink suffers a great deal in comparison to Valley Girl. Also shot in L.A. but taking place in Anytown, its class struggle is generic and feels phony. Whereas the couple in Valley Girl–the princess and the punk–are clearly from different worlds and take risks holding hands in public, Andie and Blane come across as prom queen and king. The Hughes film settles for creating a space where teenagers are taken seriously, but they aren’t challenged. There’s a noticeable lack of conflict. Ringwald and McCarthy have good chemistry, and while the soundtrack is the best of any Hughes production (with “If You Leave” by Orchestral Manoeuvres in the Dark cued up at a pivotal moment), the music pales in comparison to Valley Girl, in which The Plimsouls are the house band, Josie Cotton serenades the prom, and “Melt With You” by Modern English crashes over the end credits. Molly Ringwald is no more special than Deborah Foreman in Valley Girl, and might be less, because while Foreman’s performance is fresh, Ringwald is playing the same character from her previous Hughes films: the daddy’s girl and fashionista. Nicolas Cage is in another dimension from Jon Cryer or Andrew McCarthy, bringing outrageousness to Valley Girl that Pretty In Pink lacks. Even without the existence of Valley Girl, Pretty In Pink would be sketchy, its characters acting as if they barely see or hear each other.

Video rental category: Drama

Special interest: School Days