Pee-wee's Big Adventure at 40

Kitschy imagination, vintage props and big laughs fuel rollicking road trip

For the remainder of summer Video Days piles in a vehicle and for those who can’t take a vacation, journeys to unfamiliar places with comedies about strangers in strange lands.

PEE-WEE’S BIG ADVENTURE (1985) takes what began as midnight theater for film industry types in Los Angeles, and by taking its unusual children’s television man-child on the road to interact with folks in familiar environments, shares its retro vision of goodness, inclusion and comic irreverence with the rest of the world. Not a comedy for everyone, it is a great comedy, brimming with creativity and fun from start to finish, with big laughs, memorable performances, quotable dialogue, vintage props and one of the most vivid feature film directorial debuts ever.

Paul Rubenfeld was born in Peekskill, New York, but grew up in Sarasota, Florida, the “Circus Capital of the World.” His father–a U.S. fighter pilot during World War II–owned a lamp store with Rubenfeld’s mother. By 17, their son was appearing in local theater productions. Rubenfeld left home to study at Boston University, but after a year, applied to and was turned away by several acting schools, including Juilliard. He got into California Institute for the Arts, a Los Angeles school co-founded by Walt Disney and his brother Roy to train the next generation of animators and technical craftspeople, including actors and artists. As Rubenfeld performed in theater both in and out of CalArts, he adopted the name Paul Reubens. A CalArts student named Laraine Newman met Reubens his graduating year in 1973, and while he gave a career as a dramatic actor of stage and screen a go, Newman would be cast in a new late night sketch comedy show for NBC called Saturday Night Live. Before she left for New York in the summer of 1975, Newman, among many others, had co-founded a sketch comedy company in Hollywood. They called it the Groundlings Theatre.

Reubens would audition for and join the troupe, but the Groundlings didn’t have the permits to open a theater, conducting workshops every night and performing revues around L.A. Reubens found kindred spirits among the Groundlings in a graphic designer named Phil Hartman and a standup comic named John Paragon. In 1977, Charlotte McGinnis, a friend of a friend in Boston, told Reubens she’d gotten her AFTRA union card and almost won a prize appearing on The Gong Show, NBC’s amateur talent contest. Working with Reubens, they put together an act, calling themselves “Betty and Eddie’s Sensational Sound Effects,” vocalizing all the sound effects for an old-time radio play. Reubens and McGinnis won, and appearing on the primetime edition, won again. Through the end of the decade, Reubens would appear on The Gong Show fourteen times under a number of guises, per the rules of the Chuck Barris-hosted show.

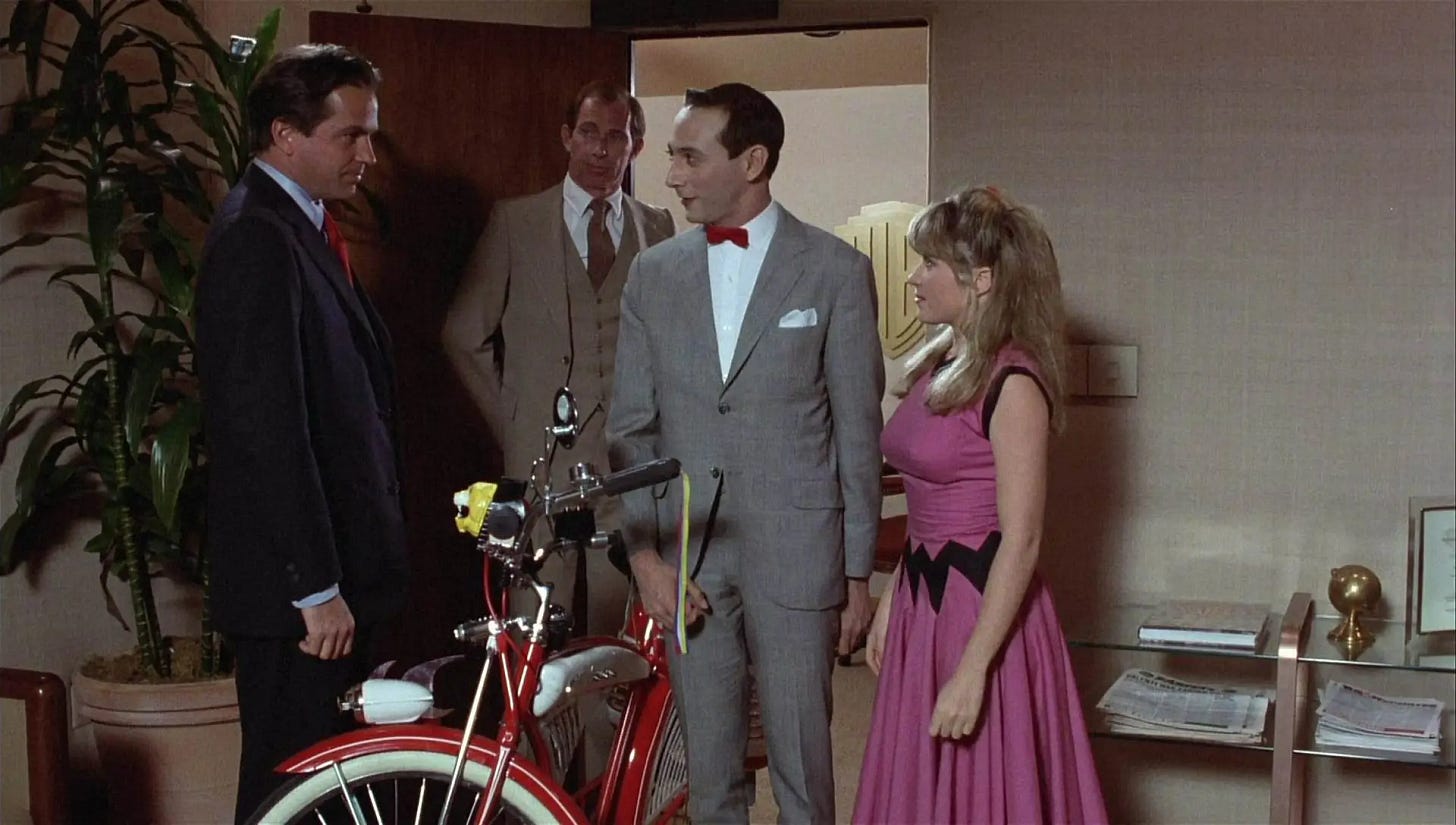

A year after his television debut, Reubens and his fellow Groundlings were given a project: create a character who’d be found at a comedy club. Needing help getting started, Gary Austin, the founder of the Groundlings, told Reubens about an eighteen-year-old aspiring comic he’d seen around the Comedy Store at one point in time named Jeff. The kid never gave his last name, preferring to be called “Just Jeff.” Banned from the floor until the bar closed at two o’clock in the morning, Jeff’s routine involved props and jokes that only went over as unintentionally funny. Reubens, who loved toys, created a baby-faced prop comedian named Pee-wee Herman, incorporating a voice he’d utilized for a play in Sarasota. Donning a gray suit, red bowtie and pants that stopped inches short of his white leather loafers, Reubens would evolve Pee-wee from a bratty hack comic to more of an innocent. Pee-wee was one of nearly a dozen characters Reubens performed in the revues, along with Jay Longtoes, the Toedancing Indian. Pee-wee seemed to separate from the others as a favorite among the audience.

In 1979, the 100-seat Groundlings Theatre opened in a space on Melrose Avenue once occupied by, among other things, a gay bar. Film industry types–network or studio executives, producers, actors–who’d started dropping by took notice of Reubens. He appeared in The Blues Brothers (1980) opposite John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd for about three seconds as a snooty waiter, and booked three episodes of a short-lived ABC sitcom called Working Stiffs in the fall of 1979 starring Jim Belushi and Michael Keaton. Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong put nearly the entire Groundlings Theatre in Cheech & Chong’s Next Movie (1980), in which Reubens played a desk clerk and appeared as Pee-wee. In the summer of 1980, Reubens’ agent got him an audition for Saturday Night Live, for the ill-fated sixth season in which Laraine Newman and virtually everyone who’d had any involvement with the show was departing. Getting as far as a final callback, Reubens was passed over for another cartoon-like geek: Gilbert Gottfried. Returning to Los Angeles and seeking his own showcase, Reubens and his agents first proposed to the Groundlings Theatre a one-man show, with Reubens performing different characters. Not wanting the Groundlings Theatre to turn into the Paul Reubens Theatre, they were turned down.

A Groundling named Cassandra Peterson had a friend who was a producer looking to create a show for late night television. Edgy enough to compete with Saturday Night Live, the show Dawna Kaufmann had in mind couldn’t be so risqué that it would run afoul with network censors. This disqualified a character Peterson was ready to launch into the spotlight in 1981: Elvira, Mistress of the Dark. Peterson suggested Kaufmann meet with Paul Reubens. While everyone gave Reubens his due as the creator of what became The Pee-wee Herman Show, some gave Kaufmann credit for suggesting the format of a children's TV program like Captain Kangaroo but for adults. With the Groundlings Theatre agreeing to give Reubens in his own midnight program provided he share their stage with other Groundlings, Reubens began assembling a cast to fit Kaufmann’s concept. Phil Hartman contributed a crusty sea captain named Captain Carl. John Paragon played Jambi, a genie visible from the neck up. As another resident of Puppetland, Lynne Marie Stewart contributed Miss Yvonne, a six-year-old’s conception of a princess. Edie McClurg played a frontierswoman named Hermit Hattie, while John Moody took on the part of Mailman Mike.

Kaufmann assembled a crew for what she considered a live TV pilot. This included Gary Panter as art director, Kaufmann a fan of his illustrations in Wet magazine and his comic strip Jimbo in the L.A. punk zine Slash. What Hartman referred to as a “mini-cult” grew around the midnight show, which was mostly attended by industry people: Steve Martin, Penny Marshall, Robin Williams. The show outgrew the Groundings Theatre, which offered a small stage–in terms of dimensions as well as its audience–and the necessity to strike the set after each performance. In February 1981, The Pee-wee Herman Show opened at the Roxy Theatre in Los Angeles and played to sold-out crowds. Reubens had convinced the cast to forgo payment for an opportunity to play for a bigger room, but rather than take the show on the road or possibly onto weekly television, Reubens and his agents struck a deal with HBO to tape and air The Pee-wee Herman Show as a one-off special on the cable network. Recorded in July 1981, the special would air in September and prove a ratings hit, introducing Pee-wee to viewers all over North America.

The popularity of the HBO special was sufficient for Reubens to receive an offer from Paramount Pictures to write and star in a Pee-wee movie. Collaborating with Gary Panter, who like Reubens had never written a screenplay, an early version of what they’d titled Pee-wee’s Big Adventure was a tropical seas fantasy Reubens compared to the Sinbad pictures, The Wizard of Oz (1939) and Mothra (1961). Panter recalled screening executives at Paramount the Gerry & Sylvia Anderson marionette puppet TV series Fireball XL5, which would inspire Trey Parker & Matt Stone to make Team America: World Police (2004). The studio didn’t get it and didn’t want to make it. Reubens kept Pee-wee in the spotlight with appearances on Late Night with David Letterman and on MTV, which were hungry for irreverent performers. William E. McEuen, manager of Nitty Gritty Dirt Band who’d also managed Steve Martin from the days the comic was opening for the jug band, was in Denver for a test screening of The Man with Two Brains (1983), trapped in the airport by inclement weather with an associate named Richard Gilbert Abramson. Catching Pee-wee on Letterman’s show, they made inquiries with Reubens’ agent about managing him.

Abramson and McEuen picked up on the similarities between Steve Martin and Paul Reubens. Both comics wore suits, both loved props, both transformed spots on TV talk shows into performance art, and while neither were to everyone’s taste, their fan base was wild, talking like and even dressing like them. Working nonstop, Martin had leapt from touring as an opening act to touring as a headliner to TV talk show appearances to TV specials to movies. Leaping Pee-wee Herman right into movies, Abramson and McEuen garnered the interest of film producer Robert Shapiro, former president of theatrical production for Warner Bros. Pictures. Shapiro had stepped down to become an independent producer, with a back channel to finance and distribution at his old studio. In partnership with Steve Martin and William McEuen’s company Aspen Film Society, Shapiro got Reubens a development deal to restart Pee-wee’s Big Adventure at Warner Bros. This time, Reubens insisted on bringing in Phil Hartman, who as much as anyone had helped him flesh out The Pee-wee Herman Show, as his co-writer. Neither of them having completed a screenplay before, Abramson, who’d co-directed a documentary about Earl Scruggs titled Banjoman (1975), brought in the film’s co-director Michael Varhol to work with Reubens & Hartman on the script.

Reubens would recall that their early template was one of his favorite movies, Pollyanna (1960), the Walt Disney production in which Hayley Mills played an orphan who reintroduces joy to the buttoned-up town she settles in. Working in a bungalow on the Warner Bros. lot, the writers substituted Pee-wee for Pollyanna and got halfway through a script. Reubens was walking with Abramson and mentioned that everyone at the studio was riding on a cool bicycle except him. A week later, Reubens reported to work to find a bike parking space reserved for Pee-wee Herman and his own 1947 Schwinn Racer, orange. Inspiration struck. Reubens & Hartman & Varhol began volleying ideas for a completely new script, one in which Pee-wee loves his bicycle more than anything in the world and when it’s stolen, sets off in search of it. Instead of changing people he’d meet in a town, Pee-wee would change those he met on the road. Six weeks later, they had a script. Reubens had embarked on a 22-city weekend tour of what was billed as The Pee-wee Herman Party, a multimedia show that included an industrial film about personal hygiene, a Pee-wee short film (Pee-wee Goes Hawaiian) and musical performance (the song, “I Know You Are But What Am I?”) Using ticket sales to bolster their case for a movie, Abramson handed Warner Bros. executives a copy of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure as the tour closed at the Universal Amphitheatre in L.A. The studio agreed to greenlight the picture, albeit at what was even then considered a low budget ($4 million) and contingent on director approval.

Reubens’ version of what happened next began with him drawing up a list of at least 100 directors whose work he’d been marginally impressed by. Returning from a visit to Sarasota, Reubens found Warner Bros. had pared down his list to one name, someone he hadn’t even suggested. The director had directed two pictures, neither of which Reubens liked or felt made him a viable candidate for his film. Given a week to find a replacement, Reubens attended a party that night and approached everyone he knew for suggestions. A member of the Groundlings named Maryedith Burrell was beside herself recommending the director of a short film she’d just seen titled Frankenweenie (1984). Produced by Walt Disney Productions and shot by one of their former animators in the style of Frankenstein (1931), the unusual film had earned a PG-rating, and plans by Disney to attach it to their Christmas 1984 re-release of Pinocchio (1940) were canceled. Frankenweenie did screen in limited engagements in Los Angeles and plenty of Hollywood people had seen it. Its director was named Tim Burton. His film featured Shelley Duvall, who’d commissioned Burrell to write several episodes of Faerie Tale Theatre and cast Reubens as the puppet who longs to be a real boy in her live action version of Pinocchio, which had aired on Showtime in May 1984.

Reubens got Shelley Duvall on the phone and the actor/ producer seconded Burton for the job. Screened Frankenweenie by Disney the next day, neither Abramson or Reubens remembered watching the whole film before agreeing that Tim Burton was the director they were looking for, few directors demonstrating the panache for art design that Burton–who attended CalArts the same time Reubens had–demonstrated. Though he had an advocate at Warner Bros. in production executive Lisa Henson, the studio dismissed Burton as a candidate to direct Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, claiming that they’d offered him numerous directing assignments and he’d rejected them all. While Burton would call the story the studio fed Reubens as fishy, it was true that he’d balked at taking a job directing his first feature, waiting for a script whose lead character he could recognize parts of himself in, or their dilemma something he’d experienced. This made Burton available, while his lack of experience also made him affordable. Warner Bros. still refused to send Burton the script, so Richard Abramson–who was producing Pee-wee’s Big Adventure with Robert Shapiro, with William McEuen an executive producer–sent it to Burton himself. The former animator agreed to direct almost immediately.

The cast came together quickly. Elizabeth Daily of Valley Girl (1983)–who’d go on to an illustrious voiceover career as Tommy Pickles on Rugrats and Buttercup on The Powerpuff Girls–was cast as Dottie, the radical bicycle mechanic who has the hots for Pee-wee. Reubens filled the cast with Groundlings–John Moody as Bus Clerk, Cassandra Peterson as Biker Mama, John Paragon as a feminine voiced knight on the Warner Bros lot, Susan Barnes as a masculine voiced showgirl, Lynne Marie Stewart as angry actor, Phil Hartman as a reporter–while Mark Holton and Diane Salinger landed big roles based on their auditions, as Pee-wee’s nemesis Francis Buxton and the Francophile truck stop waitress Simone, respectively. To play the escaped convict Mickey, Reubens remembered an actor named Judd Omen (born Fernando Cassanova) he’d worked with nearly ten years ago in a play and been wowed by. Warner Bros. insisted an experienced cameraman shoot the picture, and Victor J. Kemper, who’d worked with veterans like Carl Reiner on The Jerk (1979) and rookies like David Greenwalt on Secret Admirer (1985) and everyone in between, was hired as director of photography.

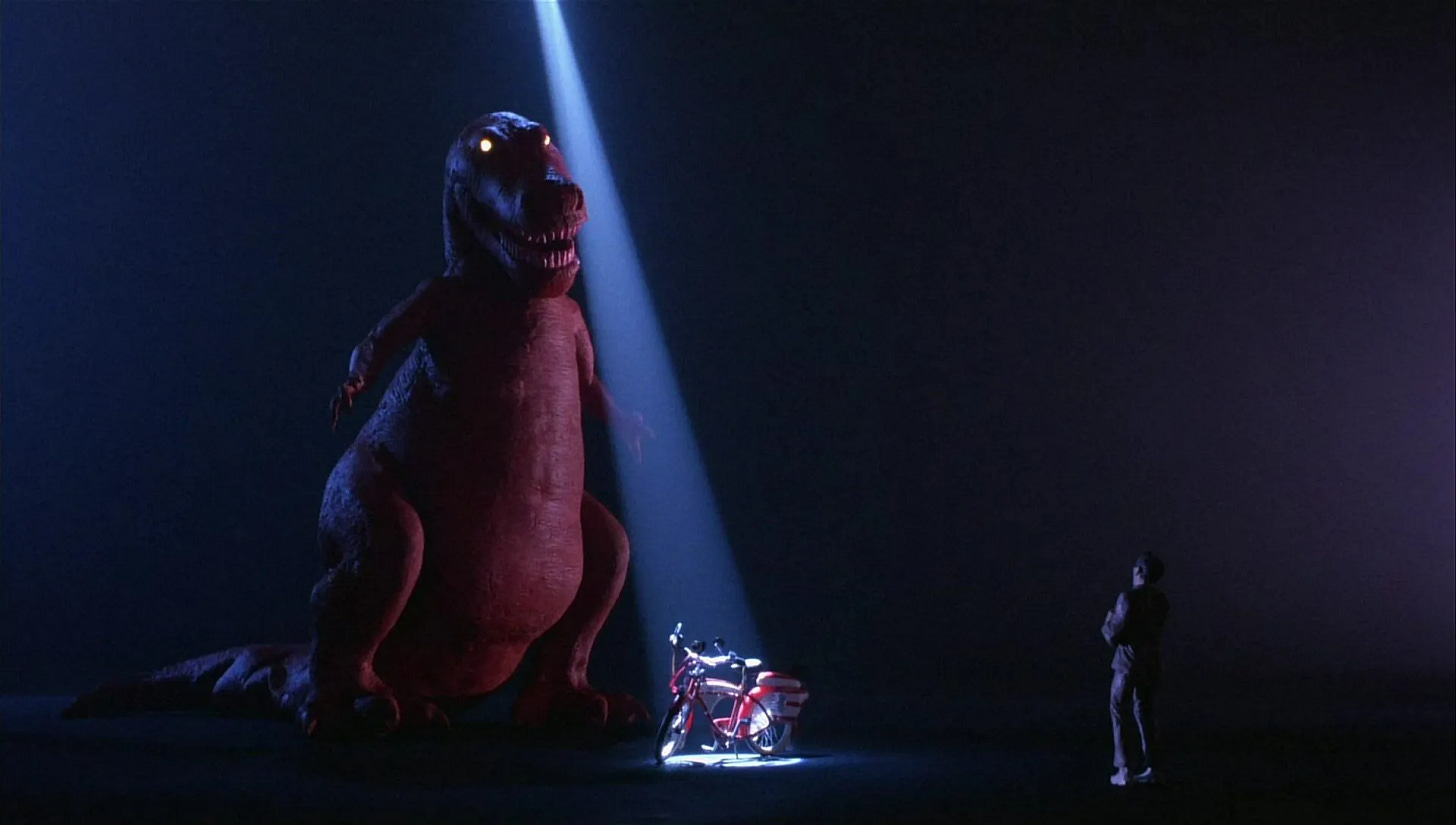

Not considering it important, the studio allowed Reubens and Burton their pick of film composers. They courted Danny Elfman, whose work Reubens was familiar with from Forbidden Zone (1982), a bizarre musical intended to showcase the L.A. musical theater troupe The Mystical Knights of the Oingo Boingo, who Elfman was musical director for. Burton knew Elfman simply as lead vocalist and guitarist for the New Wave band Oingo Boingo. Reubens (32) had never starred in a feature film, Burton (26) had never directed one and Elfman (31) had never scored one with an orchestra. To play Pee-wee’s bicycle, the Schwinn DX was chosen, a line the company introduced in 1939. To build the necessary bicycles for the film, Pedal Pushers Bikes in Newport Beach, California were contracted. Prop master Steven Levine didn’t have room in his budget to build the necessary fourteen vintage 1946-1953 DXs, so Pedal Pushers reached out to collectors to make calls to bike shops and warehouses for new old Schwinn parts. Enough parts were sourced to build six DXs, with six or seven saddlebags that could be used as replacements to keep the bikes they had rolling like new.

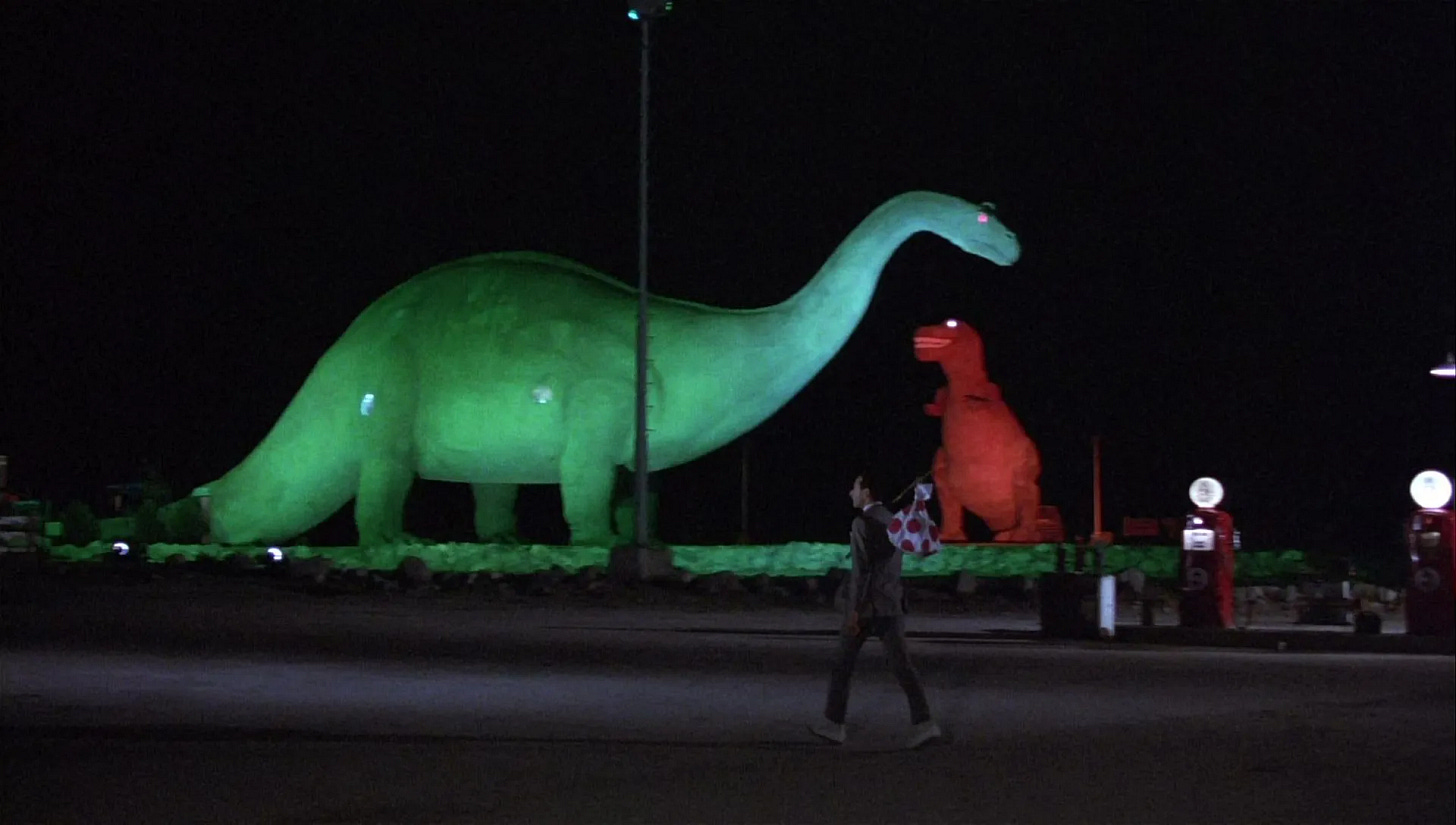

Pee-wee’s Big Adventure commenced filming in January 1985 in Los Angeles. The exteriors for Pee-wee’s house were grabbed in South Pasadena, and those for Francis’ house at the Ahmanson Mansion, a Tudor-style estate in Hancock Park. The scene of the crime was filmed at the outdoor Santa Monica Mall, before it was remodeled as Third Street Promenade and when it still had a F.W. Woolworth. The truck stop was a real location: the Wheel Inn Restaurant in Cabazon, the diner and its two dinosaur statues standing until 2016. The Alamo interiors were spoofed at Mission San Fernando Rey de España in Mission Hills. The Warner Bros. backlot played itself. The finale was shot at the Studio Drive-In in Culver City, closed in 1993 and bulldozed five years later. Interiors were filmed on stages at Warner Bros at the same time The Goonies (1985) was in production on the massive Stage 16. A closed set, Pee-wee Herman’s popularity among the adolescent cast gave him a pass to visit (while Paul Reubens would use his own name for his writing credit, Pee-wee Herman was credited as playing “Himself”).

Opening nationally on August 9, 1985 in 829 theaters in the U.S., most newspaper critics ignored Pee-wee’s Big Adventure. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert didn’t comment for their syndicated TV show until 1987, for an episode of “Guilty Pleasures” on videocassette that included The Last Starfighter (1984) and The Last Dragon (1985). While Siskel found Pee-wee’s Big Adventure predictable and couldn’t recommend it, Ebert was charmed by how innocent, playful and eccentric Pee-wee was, likening the world he occupies and characters he meets to Alice In Wonderland and The Lord of the Rings. Writing in the New York Times, Vincent Canby delivered a Pee-wee pan: “Like Marcel Marceau, he appears to be physically slight and often wears lipstick, but, unfortunately, he won’t stop talking and–worse–laughing at his own gags. Like Jacques Tati, he wears pants that are too tight, and like Jerry Lewis, he behaves as if he were a child trapped inside the body of a man. Like them all, he desperately wants to be funny, but, unlike them, he isn’t.” The film’s major competition at the box office shaped up as Back to the Future and the low budget Michael J. Fox comedy released on its coattails, Teen Wolf. Pee-wee’s Big Adventure came in #3 at the box office for three consecutive weekends in wide release and held a spot in the top ten grossing films for nine weekends, a PG-rated hit that appealed to children, teenagers in the suburbs and urban sophisticates who’d discovered Pee-wee in his HBO special or talk show appearances.

Pee-wee Herman might never have caught the public’s imagination if introduced on television in 1970 (the era of The Smothers Brothers Comedy Hour and The Sonny & Cher Comedy Hour) or 1990 (the peak of In Living Color and Def Comedy Jam). In 1980, he was right on time. Instead of commentary on whatever had made the news in those politicized times, audiences needed a breather, and Paul Reubens reached back in time to Saturday morning TV of the 1950s, and to an extent, public television like Sesame Street or Mr. Rogers Neighborhood populated by budget puppets, kitschy cartoons and fantasy worlds where everyone was welcome and no one was mocked. That was the creative direction of The Pee-wee Herman Show of stage, but what makes Pee-wee’s Big Adventure of film exciting is how it abandons nearly all of what had made Pee-wee a cult icon, forcing a man who–without explanation–exists in a bubble of Saturday morning TV in his mind to venture forth and share his outlook with folks who don’t really live in Puppetland: an escaped felon (convicted of losing his cool and cutting the manufacturer tag off a mattress), a rangy waitress who dreams of visiting France, hobos, bikers and Hollywood types. Pee-wee isn’t saddled with problems, and by finding a way to bring joy and excitement to those he encounters, isn’t treated as if he has a problem.

Reubens & Phil Hartman & Michael Varhol seed the fresh ground of their script with wonderfully irreverent characters who ricochet Pee-wee on the next leg of his journey. There’s the phony fortune teller who concocts the location of Pee-wee’s bicycle by glancing at a sign that reads “Al & Moe’s” and “basement,” a fed-up actress (Lynne Marie Stewart) whose spat with a child co-star provides a distraction for Pee-wee to steal back his bike, and in the biggest laugh, a gum-chewing Alamo tour guide (Jan Hooks) whose good cheer is even too much for Pee-wee. The gift the Groundlings Theatre gave to Pee-wee Big’s Adventure is how quickly, expertly and economically actors are able to create memorable characters. No one on this show gets caught standing around with nothing to do. The material and cast are put on a rocket by Tim Burton, working with less money and time on his feature film debut than he ever would again as a filmmaker, using that to his advantage. Rather than tell stories, the director of Beetlejuice (1988), Batman (1989), Edward Scissorhands (1990), Batman Returns (1992), Ed Wood (1994) and Mars Attacks! (1996) would specialize in creating characters, making dark and visually lavish shorts separated by filler within a larger film. Pee-wee’s Big Adventure is Burton’s best picture because there is no filler. Every five minutes is a different movie: a sports film, a cartoon, a stop-motion animation fantasy, a movie-within-a-movie, a romance, a musical. Like Reubens and Burton, Danny Elfman delivered in tremendous excess to his salary, his simple musical score bringing color and circus-like amusement to a film that couldn’t afford lighting or camera tricks, set design or even an opening credits sequence to suggest handmade spectacle, which this is.

Video rental category: Comedy

Special interest: Staff Picks

Wow Joe! Never saw this movie mainly because what little I saw of the character I didn’t like… To me he was just a little too silly over the top… But after reading your review and all the background information, I think I’ll give it a viewing… As always, great job! Thanks! Peace! CPZ