Night of the Comet

Teenage sisters inherit the world in spirited 'empty city' romp

NIGHT OF THE COMET (1984) is the opposite of a movie with impressive execution but little to no spirit. It’s a movie with intoxicating levels of spirit and middling execution, carried off competently enough we don’t mind its bumps and lags. Its scenario inverts the traditional genre story of two men surviving the apocalypse and fighting over a woman, instead focusing on two female survivors and one male, who steps out of the picture so its women can have their hand at running the world.

Thom Eberhardt attended California State University Long Beach, serving as a production assistant on a student short film titled Amblin’ (1968) directed by a classmate, Steven Spielberg. Both would drop out of school, but while Spielberg parlayed writing and directing episodic television for Universal Television on Marcus Welby M.D. or Columbo to a deal to direct four made-for-TV movies, Eberhardt landed a job with KOCE, the Orange County PBS affiliate, beginning his professional film career as an editor of documentaries. Unhappy with the projects he was being assigned to direct, Eberhardt forced himself to start writing. For inspiration, he reached back to the movies he loved as a child, specifically the science fiction thrillers of the 1950s that involved empty cities. Target Earth (1954) was about a major city (shot in Los Angeles) evacuated pending an invasion by robots, its first ten minutes Eberhardt recalling as very compelling before it turned into a talkfest. Of higher quality was The World, the Flesh and the Devil (1959) starring Harry Belafonte, Inger Stevens and Mel Ferrer in which a Black man, white woman and white man are the last standing after radioactive isotopes force the evacuation of New York. Then there was the pilot episode of The Twilight Zone airing in 1959 from a teleplay by Rod Serling: “Where Is Everybody?”

In 1978, Eberhardt was directing an after school special for public television. At lunch, he asked two thirteen-year-old girls in his cast what they would do if they woke up to find everyone else on earth had disappeared. To his surprise, their first reaction was glee, naming all the fun things they could do, expressing no remorse for their dead family or friends. When asked what they’d do if they discovered bad guys were in the city with them, the girls answered that they’d arm themselves with any of the guns around. It was only when Eberhardt mentioned their boyfriends would be dead that the girls expressed some survivor’s guilt, adding that if there were only one boy for two or more of them to share, that might be a problem. Eberhardt dashed off a script within three weeks. His working title: Teenage Comet Zombies, the world’s population having been largely wiped out by the return of Haley’s Comet save for two teenage girls. Nothing came of the script.

Eberhardt had a friend notify him in 1982 that some people who knew were looking to invest in a low budget film, a furniture manufacturer who wanted his wife to star in a movie. Whipping up a script titled Sole Survivor (1984), a hybrid supernatural/ zombie picture, Eberhardt completed it as his feature film directorial debut, seeing it play in a few drive-ins. The experience led Eberhardt to redouble his efforts to work on what he enjoyed, leading him back to Teenage Comet Zombies. The script was more than an impractical combination of apocalyptic science fiction and horror, but lighthearted “Valley Girl” characters thrown in as well. Eberhardt liked it and his office assistant at KOCE liked it. In the journey Eberhardt claimed the script made, his assistant handed it to an emergency room doctor she was attracted to. The doctor was taking a community college course with a woman he was more interested in named Jane Kegon, partner to a producer with Film Development Fund. Kegon called Eberhardt to tell him that she loved his script, but unfortunately, her partner didn’t share her enthusiasm. The partner took a meeting with Atlantic Releasing Corporation to pitch its co-founder Tom Coleman a Saturday morning cartoon series instead.

Launched in 1974, Atlantic found its niche distributing foreign films. Their gamble to go into production had hit the jackpot with Valley Girl (1983), hastily produced for half a million dollars and embraced not only by critics as a real film, but by audiences as a commercially successful one. Atlantic had so much cash rolling in, Coleman’s new concern was having to share a chunk of it with his Valley Girl profit participants. He wanted to invest in a new film and to go into production immediately, anything Atlantic could market to the youth audience of Valley Girl. Film Development Fund knew of a script that sounded like what Coleman was looking for. Reading Teenage Comet Zombies, Coleman didn’t think much of it, but his executive assistant Catherine Gallant did, and kept pressing her boss to buy it. Coleman got around to phoning Eberhardt to offer him $50,000 for the script. Eberhardt didn’t even have a literary agent yet, considering himself a director, and without an offer to direct, turned Atlantic down. A week later, Coleman gave in, with an offer of $25,000 for Eberhardt’s script and $25,000 for him to direct. Putting up a budget of $700,000, Coleman assigned the project to Wayne Crawford & Andrew Lane, writer/ producers of Valley Girl who were under contract to Atlantic.

As Eberhardt recalled, neither producer understood his script or what Atlantic saw in it, and worse, knew the studio was rewarding them with Teenage Comet Zombies instead of the Valley Girl profits they were owed. Instead of turning into a political disaster with Eberhardt as the collateral damage, Crawford & Lane went to work, first as script doctors. Now titled Night of the Comet, they helped Eberhardt pare his script down from 140 pages to a practical length, as well as fix one of its biggest flaws, resurrecting a character Eberhardt had killed off rather than match her romantically with a desirable human male post-apocalypse. Crawford & Lane handled casting. To play the older of the two Belmont sisters, Catherine Mary Stewart, who’d wrapped a picture called The Last Starfighter (1984) as the hero’s girlfriend, was paired with an actor named Helen Langenkamp in auditions. Though Stewart and Langenkamp were considered compatible types, ideal for casting sisters, Kelli Maroney, who’d played a cheer captain in Fast Times at Ridgemont High (1982), was cast as Regina’s cheerleader kid sister Samantha (several months later, Heather Langenkamp booked the role of final girl in A Nightmare on Elm Street).

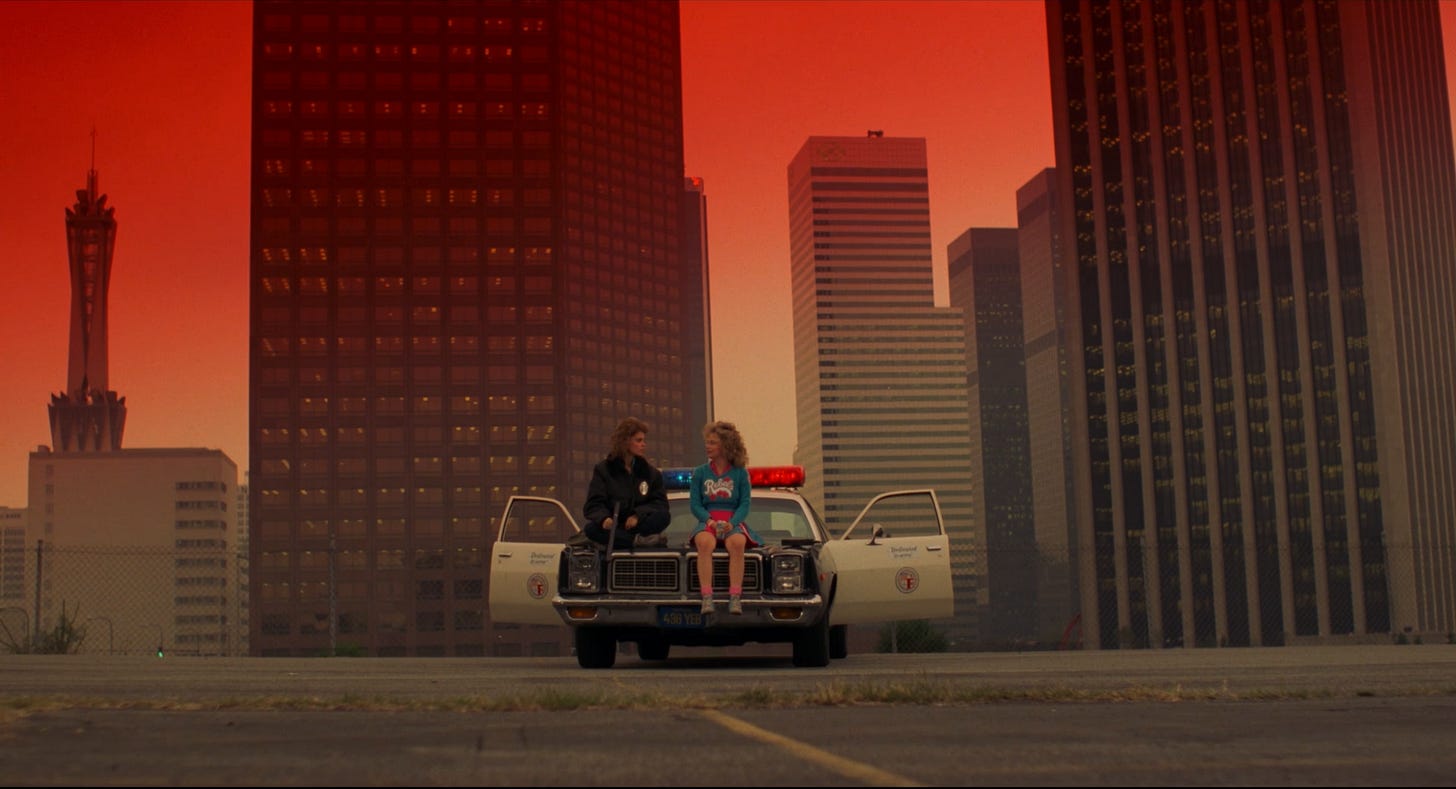

With Robert Beltran (awarded top billing as the last man in Los Angeles), Geoffrey Owens, Mary Woronov, Sharon Farrell and Michael Bowen, filming commenced in November 1983. Exteriors were shot outside the El Rey Theatre in the Miracle Mile, and in Porter Ranch for the comet party and Belmont home. The empty city was shot in downtown L.A. in the vicinity of 4th Street/ Hope Street in Bunker Hill. Without the resources to close down streets, the filmmakers studied traffic patterns and the moment downtown was deserted in the early morning hours, grabbed their shots. Interiors were filmed at Raleigh Studios in Hollywood. Stewart and Maroney came to the show as veterans of daytime soap opera, having shot hundreds of episodes of Days of Our Lives or Ryan’s Hope, respectively, valuable for a low budget film in which the director had one take to get most of his shots. According to Eberhardt, Crawford & Lane had at the very least initiated a backup plan in case he turned out to be incompetent, bringing in Crawford’s acting coach Roy London, who without Eberhardt’s knowledge, was put to work with Stewart and Maroney until the director put a stop to it. London was also on the set for at least the first week of production, standing by to replace Eberhardt, but after Atlantic got a look at the dailies, decided that either Eberhardt was competent, or that firing him was too expensive.

Eberhardt recalled his producers being upset that the characters were having too much fun and the spirit of the film too tongue-in-cheek for their taste. Atlantic actually saw financial benefits to Night of the Comet being a darkly absurd science fiction movie, like Repo Man (1984), which had played in both arthouses and grindhouses. Wrapping production in February 1984, the studio held off on a release by several months, wary of opening in late summer against the Olympic Games. To deliver the film’s music package–settling on a music budget, hiring a composer and musicians, clearing music licenses–Crawford & Lane hired music supervisor Don Perry, who’d recently taken on similar assignments for Cujo (1983) and Uncommon Valor (1983). When Perry screened the film, it had a temp soundtrack consisting of pop hits the producers hoped to license, most notably “Every Breath You Take” by The Police. That song alone would’ve cost at least $50,000 and in a favored nations clause, much more if Perry had to match what he was paying other publishers for their artists. Without the budget to do this, Perry and Bob Summer produced nineteen original songs for the soundtrack, with one cover version, vocalist Tami Holbrook performing “Girls Just Want To Have Fun.”

Night of the Comet was Atlantic’s first national release, opening wide the weekend before Thanksgiving in 1,098 theaters. Newspaper critics were effusive with praise. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert gave the film two thumbs up, Siskel crediting it as a buried treasure and citing it for being a cheerful science fiction picture as opposed to another dystopian one. Ebert enjoyed that each of the survivors were specific people. Writing for the New York Times, Vincent Canby called Night of the Comet “a good-natured, end-of-the-world B-movie.” According to Eberhardt, the film’s fortunes were made by teenagers, who saw the movie opening weekend and returned to school to tell their classmates about it, creating a wave that had the four-day Thanksgiving holiday weekend to ride out. Night of the Comet was a hit, occupying a spot among the top ten grossing films for four weeks, perhaps more if Atlantic hadn’t had to pull it from distribution. When released on videocassette, Variety would chart the film among the top fifty sellers for eight months. Most impressively, forty years after its release, Stewart, Maroney and Eberhardt are entertaining fandom and giving fresh interviews about the movie.

Something that jumps out at the viewer with Night of the Comet that Thom Eberhardt–fascinated with empty city science fiction–couldn’t have anticipated is the strength of his leading ladies. Not knowing how film marketing worked, he wrote women with agency. They wear uniforms in their early scenes, Regina as a movie theater usher, Sam a cheerleader, and having taken jobs, become those jobs. Regina is assertive, capable of chucking knuckleheads out of the house, a skill that comes in useful when handling freaked-out zombies mutated by the comet. She’s introduced at the controls of an arcade game, hyper focused by games in a manner usually reserved for boys. Where Regina stands alone as a heroine is that rather than party with everyone else on planet Earth, she chooses to get laid in the projection booth with a cad (Michael Bowen) she has little utility for beyond his benefits as a recreational activity. Rather than be punished for having a sex life, Regina is promoted for it, to leader of the free world. Sam’s world is self-centered, but as the kid sister, is allowed to react to extreme situations more like a teenager would, without apology.

Reggie and Sam are so charismatic as heroines, and Eberhardt so enamored of the days when Barbara Stanwyck or Jean Harlow were top-billed over their male co-stars in movies like The Lady Eve (1941) or Dinner At Eight (1933) that he writes himself a wide margin of error for everything else. He doesn’t seem to know who his antagonists are, shifting from creepy crawling zombies to those whose decay has turned them diabolical to government scientists starting to turn, depending on how exposed they were to the comet. There’s no science to the science fiction, the life cycle of the planet’s survivors left to whatever the production could pull out of the makeup trailer. $700,000 didn’t go far even in 1983, and the climax is flat-out boring, a virtuous scientist played by Mary Woronov and an evil stepmother by Shannon Farrell having exited the picture way too early. The bargain bin soundtrack could have been disastrous, but played today, its generic quality is actually an asset, sounding better than eighties New Wave created by AI would sound, settling into the background like music at Chess King. Eberhardt makes writing women look easy. Once Reggie not only demonstrates facility at the arcade game Tempest but a working knowledge of Superman, we know humanity is in good hands.

Video rental category: Science Fiction

Special interest: End of the World