Misery

Kathy Bates and James Caan battle in thriller about the creative process

MISERY (1990) consists of two game pieces, limited space on the board, and a stack of chance cards that keep the gameplay taut. Based on the novel by Stephen King, and made by the people who brought us Stand By Me (1986) and would bring us The Shawshank Redemption (1994), Misery is one of the good movies adapted from King’s work, laced with humor and filtered of its horror to come out as more of a comic thriller. While King’s bibliography teems with humor and suspense, the film version of Misery boasts something most of King’s work lacks: merciless editing.

Sometime in the early 1980s, Stephen King and his wife Tabitha were on their way to visit London, when the bestselling author had a dream, or inspiration, or perhaps both in midair. Scribbling a note on an American Airlines cocktail napkin, King pondered what would happen if an injured author was held captive by a psychotic fan. Under great duress, King’s abducted author, Paul Sheldon, is forced to write a novel for his captor, a murderous nurse named Annie Wilkes, livid that he has killed off her favorite literary character, Misery Chastain, heroine of a series of popular bodice-rippers. Completely off her feed, Annie plans to sacrifice her pig Misery and print her limited edition novel on pigskin, but with a joker’s grin, King imagined his macabre tale would reveal that the author’s skin has been used for parchment instead. As documented in his 2000 memoir On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft, King was sleepless in London, and asked the concierge for a quiet place to write. He was shown to a second-floor stairwell landing where a desk he was told had belonged to author Rudyard Kipling was stored.

Running on tea his first night in London, King sketched sixteen pages of notes for what he’d titled The Annie Wilkes Edition, anticipating a novella of roughly 30,000 words. He ultimately chose to title the piece Misery, ignoring the advice of his wife that critics would roast a novel titled that. Interviewed by Andy Greene for an article in Rolling Stone magazine published October 31, 2014, King continued to be candid about abusing alcohol and drugs early in his career, admitting to being a heavy cocaine user from 1978 to 1986. “I was usually pretty good about it. I was able to get up and make the kids’ breakfast and get them off to school. And I was strong; I had a lot of energy. I would’ve killed myself otherwise. But the books start to show it after a while. Misery is a book about cocaine. Annie Wilkes is cocaine. She was my number one fan.” Along these lines, Paul Sheldon turned out to be more redeemable than King had anticipated, while Annie Wilkes–his stand-in for narcotics torturing an addict–was more complex. Reaching a novel length of 110,000 words, Misery would arrive at bookstores in June 1987.

Recollections vary on who at Castle Rock Entertainment inquired about obtaining the movie rights to Misery. The film production company was co-founded in 1987 by Alan Horn (former CEO of Embassy Communications), Martin Shafer (former president of production for Embassy Pictures), Glenn Padnick (former president of Embassy Television), Rob Reiner and his producing partner Andrew Scheinman. Before it was acquired by Coca-Cola, Embassy Pictures had financed two movies Reiner directed and Scheinman produced–The Sure Thing (1985) and Stand By Me (1986)--and it was Reiner’s idea to name their new enterprise after the town in the Stephen King novella which Stand By Me had been based. With Reiner and his partners owning 60% of Castle Rock and Columbia Pictures 40%, they struck a deal with Nelson Entertainment, exchanging domestic video and foreign distribution rights for co-financing on what Castle Rock anticipated would be eighteen pictures over the next five years, plus television, with an emphasis on half-hour comedy. Patrick Goldstein in an article for the Los Angeles Times published April 29, 1990 gave Martin Shafer credit for following up on the film rights to Misery, while Reiner credited Andrew Scheinman, who apparently read Misery in paperback on a flight and thought it would make a terrific movie.

Castle Rock assumed that someone would’ve snapped up the film rights to a Stephen King thriller, but to their surprise, no one had. King had watched a cavalcade of movies based on his work–Carrie (1976), ‘Salem’s Lot (1979), The Shining (1980), The Dead Zone (1983), Christine (1983), Firestarter (1984)--play on the big or small screen, and he’d been satisfied with nearly none of them, including one King had adapted and directed himself: Maximum Overdrive (1986). One exception had been Stand By Me, based on his novella The Body, published in 1982 with three other King novellas in the collection Different Seasons. When asked by Rolling Stone in 2014 to name his favorite movie based on one of his books, King stated: “Probably Stand By Me. I thought it was true to the book, because it had the emotional gradient of the story. It was moving. I think I scared the shit out of Rob Reiner. He showed it to me in the screening room at the Beverly Hills Hotel. I was out there for something else and he said, ‘Can I come over and show you this movie?’ And you have to remember that the movie was made on a shoestring. It was supposed to be one of these things that opened in six theaters and then maybe disappeared. And instead it went viral. When the movie was over I hugged him because I was moved to tears, because it was so autobiographical.”

Not wanting to watch one of his more personal books hollowed out by Hollywood, King had not made the film rights to Misery available, but assured that Rob Reiner wanted to produce if not also direct, optioned it to Reiner and Scheinman for $1. Reiner was unsure if he was best suited to direct the material, but did agree to develop a script. He settled on commissioning screenwriter William Goldman, whose adaptation of his novel The Princess Bride (1987) had just opened with Reiner directing and Reiner and Scheinman producing. Goldman, who’d also adapted the thriller Marathon Man (1976) from his novel, knew a good torture scene when he read one, and when he reached the point in King’s novel in which Annie hobbles Paul by cleaving off his feet with an axe and cauterizing his wounds with a blowtorch, he knew he wanted to write the script. Reiner and Goldman’s first choice to direct was George Roy Hill, the prestigious director of Goldman’s original screenplay Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid (1969). Hill, who twenty years later was a long way from a hit, boarded Misery for a while, but couldn’t reconcile shooting a picture which pivoted on a character getting his feet lopped off. Reiner briefly considered offering the job to Barry Levinson before deciding he could direct Misery himself.

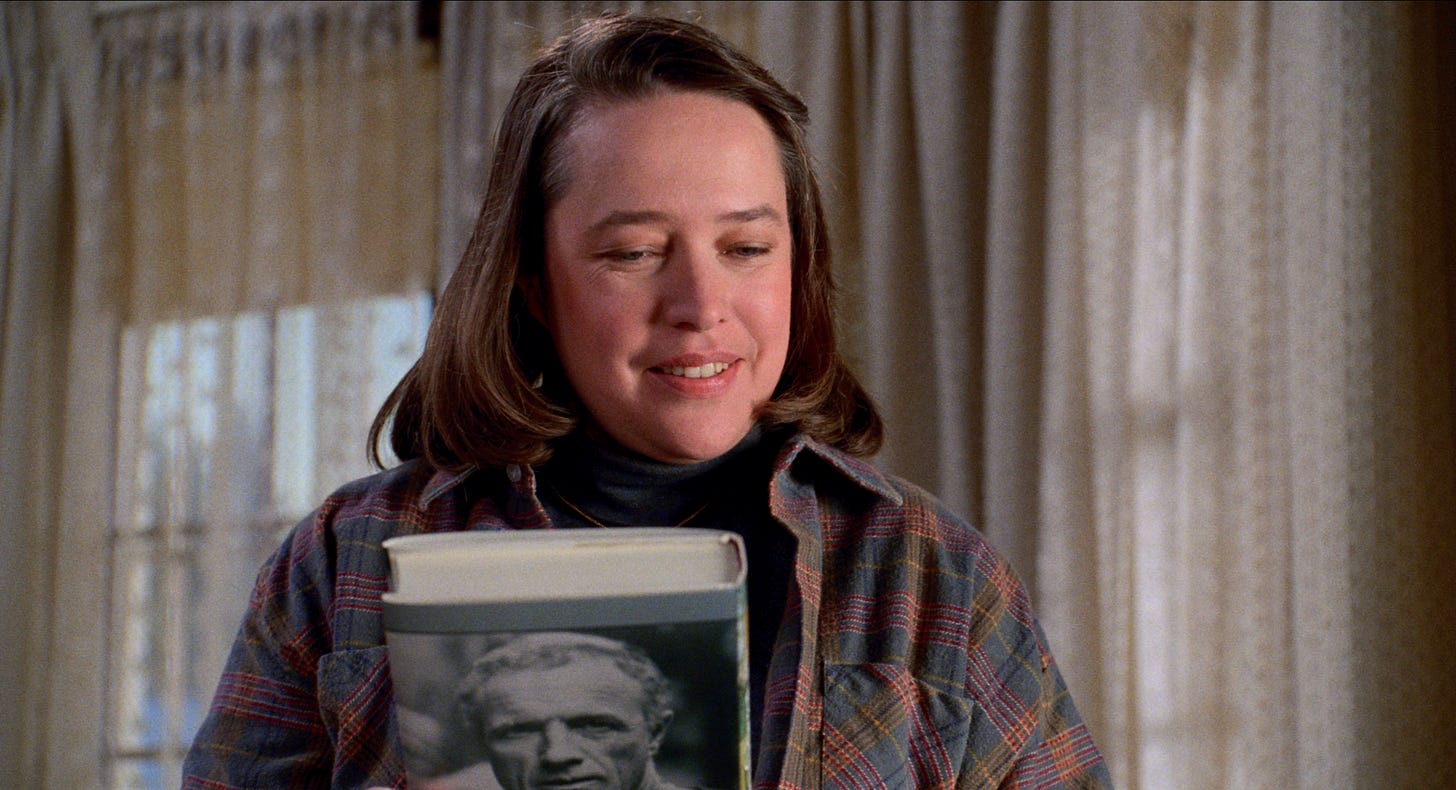

Speaking to Betsy Sharkey for a New York Times article published June 17, 1990, Reiner stated, “I don’t like horror movies. What was intriguing to me was not the horror aspect so much as the torture, the turmoil, the angst that any creative person goes through in order to try to create, in order to try to grow. It’s exactly what I’ve been through in my life–being successful at one thing and wanting to do something else and being terrified that you won’t be accepted at that.” After William Goldman turned in his first draft, Rob Reiner & Andrew Scheinman, who’d demurred taking a screen credit for co-writing When Harry Met Sally …with Nora Ephron, started fine tuning Goldman’s script. When Reiner had asked Goldman who he pictured playing Annie Wilkes, the screenwriter had responded “Kathy Bates.” Goldman had never met the actor but knew her work, Bates a Tony Award nominee in ‘Night Mother and an Obie Award winner for Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, the former of which Reiner had seen performed on Broadway. The director agreed immediately that Bates was ideal for the part.

Castle Rock was an independent producer sheltered from studio notes or casting approval, but Reiner did his due diligence by meeting a star and discussing with Bette Midler the possibility of her playing Annie Wilkes. Midler apparently confided she couldn’t see herself playing someone so “ugly” and Reiner didn’t try to change her mind. Kathy Bates had relocated to Los Angeles, where instead of movies, she was working on stage, in the L.A. tours of ‘Night Mother and later, Frankie and Johnny in the Clair de Lune, both at the Mark Taper Forum. Meeting with Reiner to read for the part of Annie Wilkes, Bates was interrupted by the director-producer early in her reading to be notified that the part was hers. Casting Paul Sheldon would be nowhere near as neat. Reiner’s first choice for the role was William Hurt. He turned it down. Goldman went as far to address some of Hurt’s concerns in a rewrite, which Hurt also turned down. Kevin Kline turned it down. Michael Douglas met with Reiner and turned it down. Harrison Ford turned it down months after passing on Ghost (1990), incredulous at playing scenes with actors whose characters were not able to see him. Ford’s objections to Misery are unclear.

Dustin Hoffman was reached by phone, and according to Goldman, the two-time Academy Award winner for Best Actor liked Reiner and liked Castle Rock, but turned Misery down. Robert DeNiro turned it down. Al Pacino turned it down. Richard Dreyfuss, a classmate and longtime friend of Rob Reiner’s from Beverly Hills High School, had come close to starring in When Harry Met Sally … before raising concerns about the script, which he thought had given its characters short shrift and needed work. Reiner chose the script over star, and later realizing he’d screwed up, Dreyfuss told Reiner he’d work on whatever Reiner was directing next. Dreyfuss read Misery and turned it down. Gene Hackman turned it down. Robert Redford took a meeting with Reiner, acknowledged that Misery would be a very commercial movie, and turned it down. Warren Beatty, who had a reputation of flirting with more acting jobs than he committed to, operated in similar fashion when it came to playing Paul Sheldon. In November 1989, Daily Variety reported that Beatty was in “serious negotiations” to take the part. According to Reiner, the actor came in every day for at least two months to work with him and Scheinman on the script.

Warren Beatty’s mission statement for Misery was that it wasn’t a horror or thriller, but a prison movie. Imprisonment was everything, and it was incumbent on them to make Paul Sheldon smart enough to escape his captivity. King’s novel, an addiction parable, dealt with Paul laying in bed and overcoming his dependence on the painkillers Annie was plying him with, but Beatty was adamant the character move around and fight for his freedom. It was also Beatty’s suggestion that the hobbling scene as King had devised it would not play to viewers the way it played to readers and needed to be rethought. Based on Beatty’s script input, Reiner and Scheinman equipped Annie Wilkes with a new set of tools to perform a different operation, and William Goldman, in his 2000 memoir Which Lie Did I Tell? admitted to being so upset over revisions to the hobbling scene that he called Reiner and yelled at him over the phone. Goldman’s tirade appeared to be academic, because after Reiner and Scheinman dialed in a script, Warren Beatty lost interest, telling the director that if he couldn’t get anyone else to play Paul, he could come back to him. Rather than conclude that no film leading man with prestige would do the part, Andrew Scheinman proposed they try James Caan.

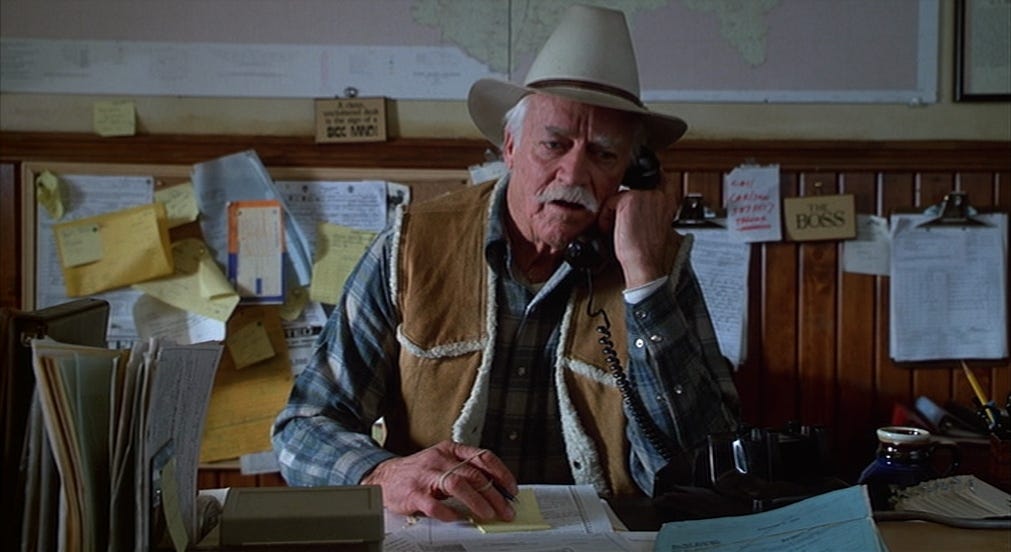

For every good movie that James Caan had worked on–The Godfather (1972), Freebie and the Bean (1974), Thief (1981)--many more–Slither (1973), Comes a Horseman (1978), Kiss Me Goodbye (1982)--had not been good, and Caan had disappeared from film between 1983 and 1987 while seeking treatment for depression and cocaine addiction. Sober and needing work, Caan jumped through hoops to win the part of Paul Sheldon and in December 1989, Daily Variety announced that he’d been cast. Bates and Caan were joined by Richard Farnsworth as the sheriff investigating Sheldon’s disappearance and Frances Sternhagen as his deputy and wife. Lauren Bacall, credited for “special appearance,” was cast as Sheldon’s literary agent in three scenes. On a budget Rob Reiner tabbed at $18-20 million, Misery commenced filming February 1990. The town of Genoa, Nevada stood in for “Silver Creek,” Colorado. Four buildings were constructed as both exterior and interior filming locations in Genoa: a sheriff’s office, a café, an auto garage, and a general store. A gas station facade and a pay phone were also installed to fill in the fictional town’s infrastructure. A facade of Annie Wilkes’ home was constructed outside the town of Clear Creek, near Lake Tahoe, Nevada. Most of the interiors, including all those in Annie’s house, were filmed at Hollywood Center Studios in Los Angeles, formerly General Service Studios and for a brief period, Zoetrope Studios, with Francis Coppola filming One From the Heart (1982) there in its entirety. The crash site was filmed in Donner Pass, in the northern California county of Placer, while the restaurant scene which ends the picture was filmed outside and inside the Biltmore Los Angeles.

Misery opened November 30, 1990 on a modest 1,244 screens in the U.S. Reviews leaned positive. On their syndicated television program, Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert gave the film two thumbs up. Filing his review in the Chicago Tribune, Siskel wrote: “This obviously could have been been routine thriller material, but it is enlivened by a wonderful performance by Kathy Bates as the crazed fan who alternates between compassion and violent kookiness–all while smiling beautifully and with a little gold cross hanging from her neck. Thrillers are defined by the freshness of their villains, and this one is unique. James Caan, who has had an erratic career, is very good here, playing the writer in a no-nonsense fashion. Explicit violence is kept to a minimum, yet I found myself covering my eyes out of tension more than once.” Siskel gave the film 3 stars out of 4. Writing in the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert stated, “It is a good story, a natural, and it grabs us. But just as there is almost no way to screw it up, so there’s hardly any way to bring it above a certain level of inspiration. Many competent directors could have done what Reiner does here, and perhaps many other actors could have done what Caan does, although the Kathy Bates performance is trickier and more special. The result is good craftsmanship, and a movie that works. It does not illuminate, challenge or inspire, but it works.” Ebert also gave the film 3 stars out of 4.

At the box office, Misery was in competition with a bevy of holiday films: The Rescuers Down Under, Rocky V, Three Men and a Little Lady (a sequel to Three Men and a Baby), Predator 2, Clint Eastwood-Charlie Sheen in The Rookie and a new fantasy film from Tim Burton titled Edward Scissorhands. Misery opened post-Thanksgiving head-to-head against Look Who’s Talking Too (a sequel to Look Who’s Talking) and Cher-Winona Ryder in Mermaids. A family comedy written by John Hughes titled Home Alone and a three-hour western directed by Kevin Costner titled Dances With Wolves defied expectations to become the season’s blockbusters, but Misery spent six, nearly seven weekends among the top ten grossing films in the U.S. It received an Academy Award nomination, for Best Actress (Kathy Bates) and despite being counseled by Reiner that industry voters rarely rewarded thrillers, Bates won the Oscar. Lead roles in several feature films followed: Fried Green Tomatoes (1991), A Home of Our Own (1993), Dolores Claiborne (1995), as did supporting roles in Titanic (1997) and The Waterboy (1999).

Misery is not a flawless movie. It feels like a flawless movie. The characters–none of whom realize they’re in a Stephen King story–take time to catch up with the viewer. Annie’s anger boils from foul temper (furious at Paul when she discovers that he knocked off Misery Chastain in the freshly published Misery’s Child) to emotional torture (compelling him to cast the match to incinerate the manuscript she’s recovered from his car, which she deems “filth”). This slower build is necessary to lure us in and it’s at the 41-minute mark when Misery takes off. This is when Annie lugs an antique Royal typewriter and glossy Corrasable paper into the guest room and Paul realizes that to live a while longer, he has to write the book of his life. Misery isn’t simply about being held hostage by a murderous nurse, it’s about being held hostage by the creative process. His legs smashed, his right arm nursed in a sling, the world believing he’s dead (all of which could be filed under “resistance”), if Paul is unable to resurrect his heroine for Misery’s Return, his host will have no further use for him. Sort of like, readers for a writer who won’t write. This scenario is not only a delight for book lovers–with King, William Goldman and Rob Reiner making sport of the sort of disposable romance novel that sells more copies a year than every other type of book combined, Annie Wilkes their critique of the reader addicted to them–but also introduces a good deal more levity into the story that the horror show that is King’s novel, which includes more torture.

The film adaptation turns mostly on suspense. Like a rat in a maze, Paul Sheldon realizes that he can’t outmuscle or outrun Annie, can’t outsmart her because she knows everything about him ever printed, and can’t out reason a psychopath with several victims to her credit. Kathy Bates offers no tells, hints at no exploitable weaknesses with Annie, until Paul discovers one that should bring joy to the heart of any book lover: the power of fiction. James Caan is equally potent. His casting brings certain qualities that Warren Beatty might’ve–his situation rendering his athletic prowess or way with women useless–but unlike Beatty, Caan makes Paul relatable, a guy from our neighborhood who goes step by step trying to escape his predicament just like we would. Barry Sonnenfeld, who’d photographed Raising Arizona (1987), Throw Momma From the Train (1987), When Harry Met Sally … and Miller’s Crossing (1990) before making the rare leap from cinematographer to director, does a yeoman’s job pushing the camera into Bates’ or Caan’s face at moments of anxiety, or exploiting detail—like a keyhole, a ceramic penguin, or a match—unlike King’s novels, which are often overloaded with stuff that can be easily tossed. As directed by Reiner, there’s not an ounce of fat on Misery, and he matches King’s sense of humor by using Annie’s favorite musical artist, Liberace, throughout the soundtrack.

Video rental category: Mystery/ Suspense

Special interest: Prison Break

Hey, good morning Joe! Merry almost Christmas… This movie, Misery, I remember enjoying immensely when I first saw it… I believe I’ve seen it several times on TV since then, and I am still moved to a state of “Holy Shit” by Kathy Bates performance… thank you, thank you, thank you for the background information critique and analysis… Always such a fun read, great job, Joe! Peace! CPZ