Midnight Run

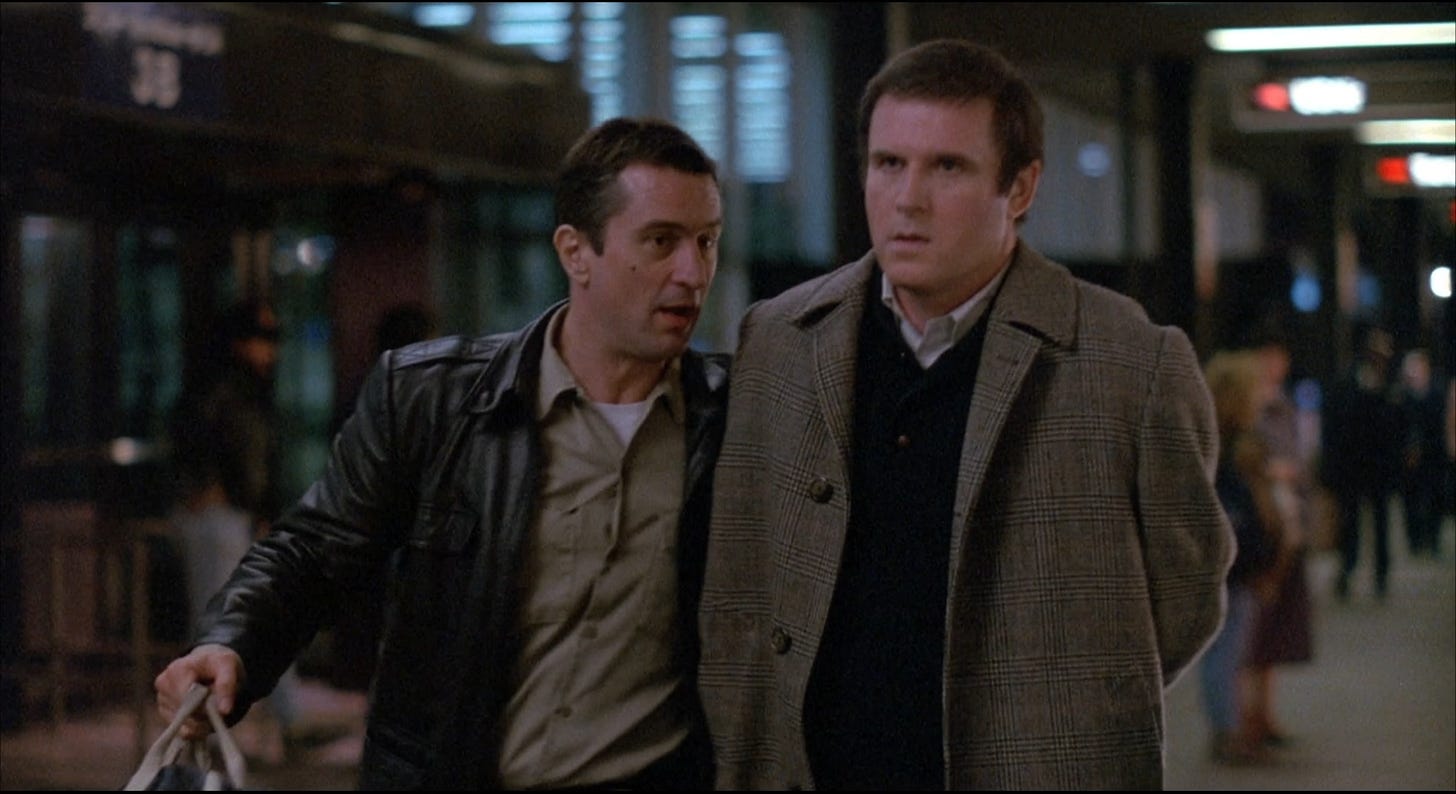

Robert DeNiro & Charlies Grodin incomparable in soft action/comedy

MIDNIGHT RUN (1988) boasts two of the great underrated film performances of the era, Robert DeNiro and Charles Grodin committing them in a light entertainment which would’ve been released on the bottom of the bill in the fifties or sixties, and in the nineties and aughts, ran on basic cable television for years. Rated R by the MPAA for “pervasive strong language throughout, and for some violence,” the movie is so benevolent, and its lead actors have such delightful, one-in-a-thousand chemistry, the movie’s considerable flaws are papered over.

Leading up to the release of Wise Guys (1986), screenwriter George Gallo sold a pitch to producers Don Simpson & Jerry Bruckheimer about cops who trade places, one married, one single. The script they commissioned, titled Bulletproof Hearts, was eventually produced with Martin Lawrence and Will Smith as Bad Boys (1995). As part of his research, Gallo was introduced to Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department detective Sgt. Stanley White. The sergeant told Gallo about a time he flew to Florida to escort a suspect back to California, and because the man exercised his civil right to refuse transportation by air, White and his partner spent five days with him on a road trip. Gallo, who was so uncomfortable aboard airplanes he rode Amtrak cross country, thought this sounded like a road movie. Movie cops were becoming old hat by 1986, so in the script he started writing, Gallo made his characters bounty hunters. He was at Paramount for a meeting with Simpson and walking back to his car, bumped into Martin Brest in the parking lot. Brest, director of Beverly Hills Cop (1984), had heard about Bulletproof Hearts, but didn’t want to direct another cop movie. He asked Gallo what else he was working on. Gallo began meeting with Brest in his office to talk about the films they loved, like The Hot Rock (1972) and The Friends of Eddie Coyle (1973), and to concoct a movie Brest had in mind about a gold heist. Gallo got around to mentioning his unfinished bounty hunter script, titled Midnight Run. Brest read it and told Gallo to finish it. He wanted to direct.

In Midnight Run, a Los Angeles-based bounty hunter travels to New York on a skip trace, tracking an accountant who stole money from the mob and gave it away to charity, but when the fugitive refuses to fly, the bounty hunter has five days to get his prisoner to L.A. to collect his fee, with both the FBI and the mob looking to get to the accountant first. Gallo compared it to The Last Detail (1973) if instead of just letting loose a stream of obscenities, the main character was being shot at for trying to bring in a prisoner. With Martin Brest serving as his own producer and setting the project up at Paramount, Gallo met with bounty hunters to pick their brains. These included Stan Rifkin, who John Ashton would base much of his character, Marvin Dorfler, on. In contrast to the skip tracers who seemed drawn to the cowboy lifestyle, Gallo was impressed by Bob Burton, regarded as the nation’s premier bounty hunter, a gentleman who seemed less of a buckaroo and more like someone who had a score to settle. This formed the foundation of Jack Walsh. As Gallo huddled with Brest to work out the intricate plot, his script became less edgy and violent, changing into something more good-natured and funny.

While Gallo had written the role of Alonzo Mosley, FBI, with actor Yaphet Kotto in mind, Jack Walsh and Jonathan Mardukas were blank slates. Brest’s agent at CAA, Jack Rapke, suggested Robert DeNiro. Stories of how he’d put on eighty pounds for his Academy Award winning role of Jake LaMotta in Raging Bull (1980) had earned DeNiro the reputation as the greatest actor of his generation, but he worked infrequently, starring in twelve films since his breakout year in 1973, few if any of them packing in crowds. DeNiro had wanted to make a comedy, meeting with director Penny Marshall for the lead in Big (1988) before both sides agreed that someone like Tom Hanks would be more appropriate. With chemistry such a vital ingredient for Midnight Run, auditions commenced for the part of DeNiro’s co-star. Most of the actors seemed intimidated. Charles Grodin was a bright exception. Grodin had been cast as a leading man by Elaine May in The Heartbreak Kid (1972), but had since played the heel in movies like Heaven Can Wait (1978), Seems Like Old Times (1980) and The Great Muppet Caper (1981). While studio president Ned Tanen was anxious about DeNiro’s ability to attract a wider audience, he refused to bank on Grodin. Tanen argued that the actor wouldn’t even be available by the start date Paramount was aiming for. He suggested the script be rewritten so that a woman might play Mardukas. This gave Brest and DeNiro fuel to hold sham auditions, interviewing men and women, dragging out the casting process until Grodin became available.

Staring at a production budget of $31 million, Tanen canceled the film. Brest called Casey Silver, the former director of development for Simpson/ Bruckheimer who was now VP of Production at Universal Pictures. Silver sold his boss, new studio chairman Tom Pollock, on Midnight Run, and within one day of being put in turnaround, Universal picked it up. With John Ashton, Yaphet Kotto, Dennis Farina and Joe Pantoliano joining the cast, filming commenced in October 1987. The G.M. Hoff building in downtown Los Angeles served as Moscone’s office, and Grand Central Market where the bail bondsman meets Walsh. Exteriors for the Duke’s apartment were filmed in Brooklyn Heights, New York. Grand Central Station was used as a major location, as were McCarran International Airport in Las Vegas for the climax and Los Angeles International Airport for the final scene. The Chicago Bus Station, the Amtrak station in Niles, Michigan, the town of Globe, Arizona, and the Blue Angel Motel in downtown Las Vegas were also used. The scene where Jack and Mardukas are swept into a river was planned for Salt River Canyon in Arizona, but after DeNiro barely survived his plunge, the production went to New Zealand, where waters were warmer in January, for Grodin to fall into the drink. Reports indicated the film went over budget by $9 million.

Midnight Run opened July 1988 in the U.S. in 1,158 theaters. Test screenings had gone so far through the roof that Twentieth Century Fox made certain Die Hard wouldn’t open against it. Reviews were consistently positive. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert gave the picture two thumbs up, Siskel comparing the travel companionship between DeNiro and Grodin to Steve Martin and John Candy in Planes, Trains and Automobiles (1987), with A+ material instead of a B, while Ebert credited the depth and subtlety DeNiro and Grodin brought to their characters. Considered superior to Beverly Hills Cop, which was at that time the highest grossing R-rated film ever made, Midnight Run opened softly and spent only five weeks among the top ten grossing films, an underwhelming commercial run given its budget. The film found its audience on basic cable television, gaining popularity as a great buddy movie. By the time Universal was marketing The Hard Way (1991), in which James Woods played a tough cop stuck with a movie star played by Michael J. Fox, the studio compared it to Midnight Run (the comparison was much better than the movie).

For all of its expletives, Midnight Run marked a shift in tone from the gritty, pulp edge Martin Brest brought to Beverly Hills Cop–a movie conceived in the late seventies and drawn up for Sylvester Stallone–for a softer approach that should’ve been at home in the late eighties, with a redeemable and ultimately lovable Robert DeNiro. It’d take eleven more years for audiences to discover that with the right material, DeNiro was funny, Analyze This (1999) and Meet the Parents (2000) opening the floodgates for sequels and a succession of roles where instead of creating a character, DeNiro was paid to parody the tough guys he’d played in far better films. Had it been a hit, Midnight Run might have initiated the actor’s self-destruct sequence a decade earlier. Its quality is marginal. The FBI agents are written as the Keystone Kops, while the mobsters gunning for Mardukas are even stupider, the gang who can’t shoot straight. The climax, in which Walsh attempts to incriminate the crime boss responsible for his ouster from the Chicago PD and the dissolution of his marriage, is howlingly bad movie material, unfolding at McCarran Airport with the FBI observing the action in plain view.

The film’s action scenes–one involving a helicopter shooting at Walsh, Mardukas and Dorfner and hitting everything but those men–are not only tedious, but are carried off in a cartoon style, like a comedy all involved would shrug and admit they made for their families. A sense of repetitiveness sets in. Since characters aren’t allowed to die in this cozy adventure, scenes transition by having someone popped in the jaw and losing consciousness. What Gallo and Brest do credibly in Midnight Run is set Walsh and Mardukas in opposition. DeNiro’s character has to transport Grodin to L.A. in order to get back to something resembling a life. Grodin’s character has to escape or else he’ll likely die in jail. Someone is set up to fail fatally, but the script ingeniously figures a way to give both men what they want. At the time of its release, Robert DeNiro and Charlies Grodin were a revelation, neither actor previously challenged to anchor a buddy comedy like Silver Streak (1976) or 48 HRS. (1982), and their chemistry is still something to marvel over. Given how few movies focus on male friendship in a genuine way, Midnight Run ends on an especially poignant note, with two men saying goodbye for what they know is the last time. The film is a must-see in terms of watching two master actors work, the less time spent acknowledging everything else, the better.

Video rental category: Comedy

Special interest: On the Road

Hey Joe, first things first… When I watch a movie, I totally suspend any logic or intelligence or anything resembling critical thinking… I immerse myself in the characters and totally empathize with any fabricated drama or tension that they experience… So if I find a movie enjoyable or funny, it’s an immediate reaction and I couldn’t tell you why… That’s why I so enjoy your analysis and background critiques… I always feel enlightened to learn that a director had some experience in his life, and why he wanted to choose a particular actor… Or he lived in a neighborhood that had certain influences that informed his choice of locations or music or whatever… Having said this, I thoroughly enjoyed Midnight Run, and am completely oblivious to its shortcomings and fails as you’ve outlined… But it is always so interesting to read your analysis and critique. It’s so reminds me of another movie, Bulletproof, with Adam Sandler and Damon Wayans, a movie, which I also found hysterically funny. As always, thank you for your insight, analysis, and background information… A great job! Peace! CPZ.