Manhunter

Hannibal Lecter is born in masterful, synthesized faerie tale for adults

Video Days orders readers to surrender their badge and gun and while suspended for the month of May, return to ten films trafficking in law and order.

MANHUNTER (1986) is a faerie tale for adults, utilizing modern stagecraft to tell the story of a hunter who enters a dark forest to slay the monster terrorizing a village. It has an adulterous relationship with its source material–Thomas Harris’s novel Red Dragon, the introduction of Dr. Hannibal Lecter to modern myth–jettisoning the title, paring backstory, and even changing the spelling of Lecter’s name. A loose adaptation, it is nevertheless enthralling in terms of writing, acting, camerawork and music, and leaves a lasting imprint as one of the decade’s key films.

Thomas Harris was born in Jackson, Tennessee in 1940, but grew up in Coahoma County, Mississippi, where his family grew wheat, soybean and cotton. He attended Baylor University, majoring in English, and later worked as a reporter in Waco. A magazine assignment took Harris to a prison in Monterrey, Nuevo Léon in 1962 to interview Dyke Simmons, an American who’d bribed a guard to help him escape, only to be shot in the leg and double crossed by his partner. Harris met a physician named Alfredo Balli Trevino, who not only treated inmates like Simmons for free, but members of the community as well. Highly intelligent and exceedingly polite, Trevino wasn’t on staff, Harris was notified by the warden later, but serving a life sentence for murdering his boyfriend in 1959 and cutting the corpse into pieces for burial. The doctor was suspected in the murder and dismemberment of several hitchhikers and was known as “the Wolfman of Nuevo Léon.”

In 1968, Harris took a job with Associated Press in New York. With two other reporters, he hammered out the story for a novel about a Palestinian terrorist group calling themselves Black September who recruit an American pilot to help them detonate an explosive device over the Super Bowl. Splitting their advance, Harris adapted the story to a novel titled Black Sunday. While caring for his father in Mississippi, Harris started work on his follow-up, which was about the FBI’s Behavioral Science Unit leading the hunt for a serial killer known as the Tooth Fairy, with a captured murderer named Dr. Hannibal Lecter providing his expertise, just as several incarcerated serial killers were doing with the bureau at the time. Red Dragon was published in December 1981, well after the galleys had come to the attention of Richard N. Roth, producer of Julia (1977), credited as “Richard Roth” but not to be confused with Richard A. Roth, who produced Outland (1981). Roth had a development deal with Warner Bros. Pictures and sold the studio on optioning the film rights to Red Dragon.

Roth was an admirer of The Elephant Man (1980) and like many in the film industry at that time, wanted to work with David Lynch. The filmmaker had written an interdimensional mystery titled Ronnie Rocket that wasn’t Roth’s material, and having commissioned Walon Green to adapt a script, proposed that Lynch direct Red Dragon. Lynch spent at least a year attached to the thriller before realizing that it wasn’t his material (Lynch was writing a murder mystery set in a small town, which Roth would executive produce and Lynch direct in 1986 as Blue Velvet). Roth found a better match between Thomas Harris’s novel and filmmaker elsewhere. Michael Mann had written the first three episodes of Starsky and Hutch, created the Robert Urich series Vega$ and won an Emmy Award writing the TV movie The Jericho Mile (1979), which he also directed. As part of his research into crime and punishment, Mann had interviewed and corresponded with convicted murderer Dennis Wayne Wallace, a laborer from Paramount serving a life sentence for clubbing a man to death and dissolving the corpse in a bathtub of sulfuric acid. Wallace believed his victim had sold drugs to a topless dancer he’d fixated on–not to harm, but to rescue. He confided to Mann that their love song was Iron Butterfly’s psychedelic rock tune “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida.” Mann couldn’t find a way to incorporate this pathology into a film, until he was sent Red Dragon, crediting it as the best detective story he’d ever read.

Warner Bros. had lost interest in Red Dragon, placing the project in turnaround. In his search for finance and distribution, Richard Roth snared the interest of mogul Dino De Laurentiis, who set the project up at MGM/UA. Initially a co-financier, De Laurentiis was tired of granting his studio partners videocassette and cable television rights, which by the mid-eighties, were lucrative enough to cover half the budget for many of his productions, like Red Sonja (1985) and Year of the Dragon (1985). De Laurentiis had built a production facility in Wilmington, North Carolina, and seeking his own distribution pipeline, completed the purchase of Embassy Films in September 1985. This enabled the mogul to found DEG (De Laurentiis Entertainment Group), putting up $14 million to bankroll Red Dragon himself, with Richard Roth producing, Michael Mann adapting the screenplay and directing, and DEG owning the negative. Seeking a director of photography for his production of the James Clavell novel Tai-Pan (1986), De Laurentiis had brought Dante Spinotti to the U.S. to interview. The film’s director didn’t believe that Spinotti’s work in Italy qualified him for a historical epic, but Mann liked what Spinotti had done with an Italian/ German film titled The Berlin Affair (1985) and hired him to light Red Dragon. It would become the first of five collaborations between director and cinematographer.

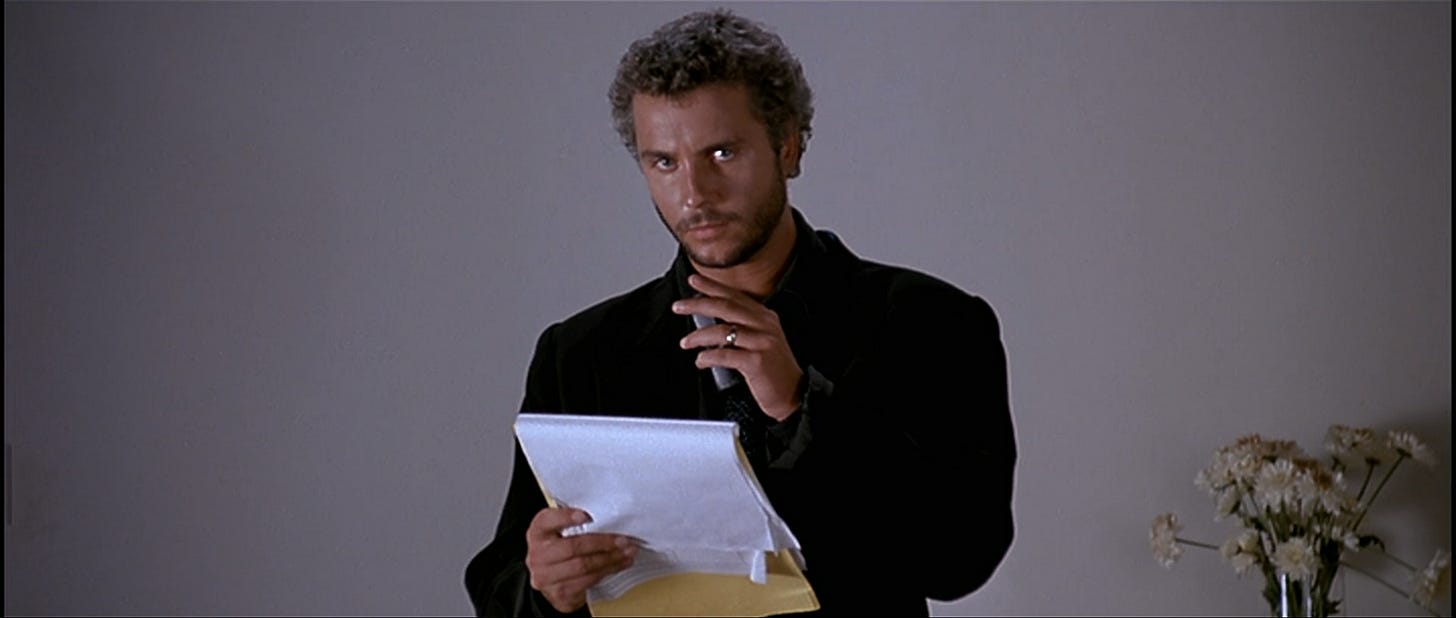

To play Will Graham, several leading men were considered or approached: Richard Gere, Mel Gibson, Paul Newman. None were available or interested. Mann, who grew up in Chicago, had worked with a local actor named William Petersen on Thief (1981), casting him in a bit part as a bartender. Now a rising star who’d been cast as the lead in To Live and Die In L.A. (1985), Petersen accepted the role of Graham. Mann considered casting the director of To Live and Die In L.A., William Friedkin, another Chicago native, as Hannibal Lecter, but without any acting experience or inclination to start by playing a serial killer, Friedkin declined. Brian Dennehy agreed to take on Lecter, but heavily in demand, dropped out and recommended a Scottish actor he’d seen in a play called Rat In the Skull named Brian Cox. Filling out the primary cast were two more actors from Chicago–CPD detective turned actor Dennis Farina as Graham’s boss Jack Crawford, and Joan Allen as a blind woman who becomes involved with the killer–and two from New York: Tom Noonan as Francis Dolarhyde, the so-called “Tooth Fairy,” and Stephen Lang as tabloid journalist Freddy Lounds. Kim Greist was cast as Graham’s wife.

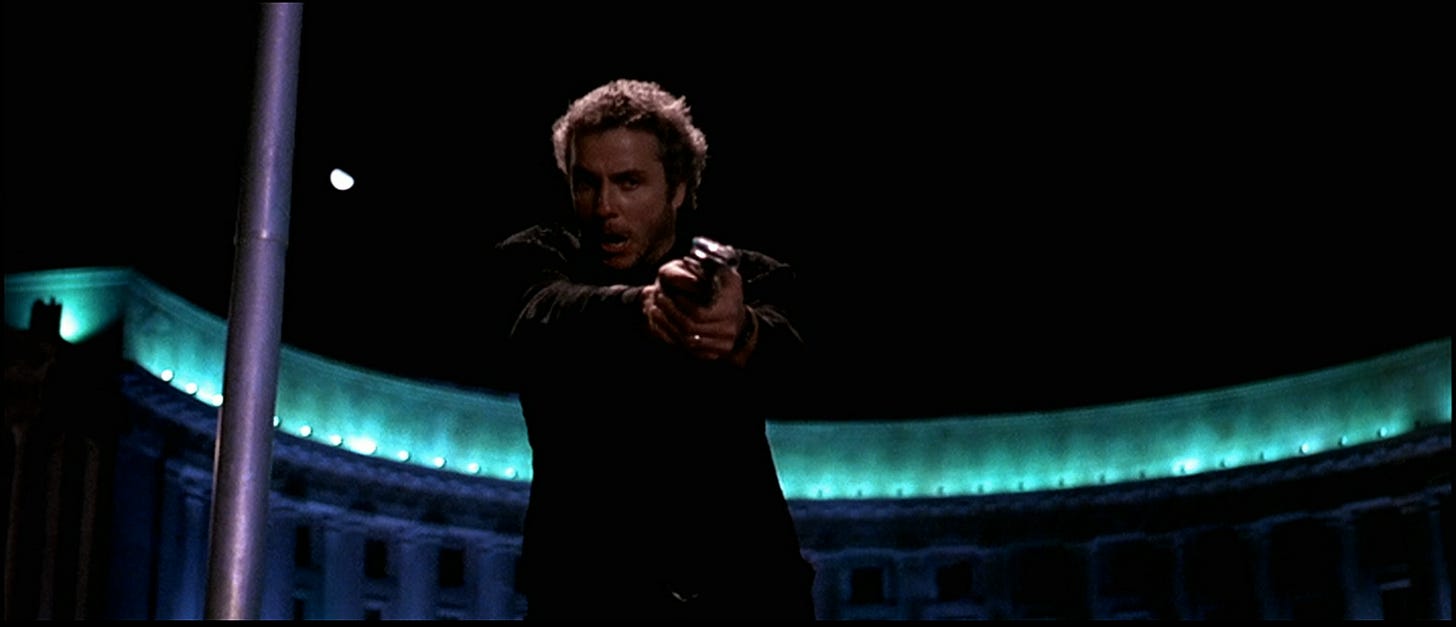

Red Dragon commenced shooting in September 1985. Will Graham’s beach house was filmed on Captiva Island, Florida, in a home owned by painter Robert Rauschenberg. Most of the interiors, including the scene in which Tom Noonan and Joan Allen act with a sedated tiger, were shot at North Carolina Film Corporation Studios in Wilmington, while Francis Dolarhyde’s abode was constructed on the Cape Fear River south of the city. The Atlanta Marriott Marquis hosted Will Graham during his visit to the city, the atrium and exterior of High Museum of Art doubled for the facility Graham questions Lektor, while the cafeteria and exterior of Herman Miller furniture showroom stood in for those areas of “Gateway Film Laboratory” where Dolarhyde works. Astrolab, the last remaining motion picture processing lab in Chicago when it closed in 2013, was utilized for the work scene between Noonan and Allen’s characters. Unable to film aboard a commercial airliner, Mann booked seats for his requisite cast and crew on a United Airlines 747 bound from Chicago to Orlando, smuggled lighting, camera and sound equipment in carry-on luggage and without asking, shot the scene where Graham falls asleep studying crime scene photos (The flight crew were not amused and were placated with crew jackets). The parking lot in Washington D.C. where Graham and the FBI set up a sting for Tooth Fairy was filmed in Freedom Plaza, in front of the Wilson Building.

As Red Dragon was in pre-production, a network television police procedural called Miami Vice concluded its first season. Michael Mann hadn’t created the program, nor would he direct an episode, but had been hired by NBC as an executive producer, designing the show’s look and feel, which owed as much to cinematic techniques in lighting, editing and music as it did MTV. Miami Vice hadn’t performed particularly well in the ratings its debut season, but during summer reruns in the weeks before Red Dragon went into production, it exploded in popularity, breaking into the top ten most watched shows per Nielsen Media Research. Mann continued to supervise script development in L.A., casting in New York, and shooting in South Florida by phone while working on Red Dragon. It was during production that Dino De Laurentiis insisted on changing the title. Not only had Red Sonja and Year of the Dragon opened to dismal box office, but market research suggested that rather than Red Dragon being associated with a bestselling thriller, too many people assumed it was a martial arts movie. Mann offered a cash prize for the cast or crew member to come up with an alternative.

Manhunter opened in mid-August 1986 in 779 theaters in the U.S. Among the newspaper critics who weren’t on vacation and screened the film, reviews leaned positive. Gene Siskel would pin it with three-and-a-half stars in the Chicago Tribune, citing “another mesmerizing, seeming non-performance” by William Petersen. David Ansen in Newsweek referred to it as a “slick and unnerving procedural thriller.” In 2001, Marjorie Baumgarten, Austin-American Statesman film critic, declared that Manhunter might be her favorite of the three Hannibal Lecter thrillers produced to that point. Richard Corliss of Time magazine was enthralled, citing what he summarized as Michael Mann’s “nouveau slick style: a strong silent leading man with a superb supporting cast, a flair for intelligent camerabatics, a bold, controlled color scheme, an assertive avant-rock soundtrack.” Much like Embassy Pictures before Dino De Laurentiis bought it, DEG struggled getting Manhunter into theaters and supporting it with a sufficient marketing campaign. Opening head-to-head against The Fly, the summer’s holdover blockbusters–Aliens, The Karate Kid Part II, Top Gun, Ruthless People–also proved more popular with audiences. The inexpense of Manhunter and the fact that DEG retained all of the film’s ancillary rights gave it the profile of a sleeper hit.

Allowing that Michael Mann was tasked with adapting a novel and needed to unload a good deal of material, Manhunter is missing a couple of things a police procedural needed. Mann didn’t realize what he had with Hannibal Lecter, whose backstory (we’re told that “Lektor” was a psychiatrist murdering coeds, nothing more) is that of a mere supporting player. It is odd today watching Brian Cox in the role–Anthony Hopkins won an Academy Award for Best Actor playing Lecter in The Silence of the Lambs (1991) and further made the character his own in Hannibal (2001) and Red Dragon (2002)--but Mann fails Lektor as a writer and Cox as a director. The character is not integrated into the narrative well, the doctor’s attempts to jeopardize Graham and his family never followed through, while Cox is directed as if Mann sees Hannibal Lecter as a boilerplate death row inmate, a truck driver who preyed on prostitutes, perhaps, rather than a psychiatrist with impeccable manners and most importantly, mastery of the human mind. The theatrical cut is missing a scene that Mann did write and shoot in which Graham visits the family he saves from being slayed by Tooth Fairy, and its inclusion would’ve clarified why the manhunter breaks his promise to his wife not to get directly involved in the manhunt.

Manhunter is a classic due to how skillfully each section of its orchestra builds a heightened sense of reality, its conductor pulling pages of temp music and putting them to service of a larger vision. William Petersen gives one of the most dexterous film performances an actor could give, called upon to portray Graham as a passionate husband, attentive father, and a master detective, processing post-traumatic stress but also relentless when on the prowl. As Francis Dolarhyde, Tom Noonan would’ve needed to be built if he didn’t exist, a 6’5” bodybuilder addled by the trauma of child abuse. Joan Allen is given a terrific character as Dolarhyde’s coworker, a film processing technician whose blindness has heightened rather than limited her libido. The provocative music–by Michel Rubini, a session pianist for every pop star up to Michael Jackson on the Bad LP and music composer for The Hunger (1983)--is matched seamlessly with a striking lighting scheme by Dante Spinotti. Despite its flaws, Mann’s screenplay focuses on a manhunt waged largely in the mind, like a scout cutting for sign rather than a cowboy blazing his six-shooters. A scene between Petersen and the child playing his son in a grocery aisle is as stark in its honesty as the diner scenes between James Caan & Tuesday Weld in Thief (1981) and Al Pacino & Robert DeNiro in Heat (1995), both written and directed by Mann, in which two people in a cynical world level with each other. It’s all the reassurance we need to know that it’s too early to give up on the human race.

Video rental category: Staff Picks

Special interest: Catch the Psycho

Millennial wife from Poland… 🇵🇱 ;)

The color schemes and cinematography/lighting really captivated me. I’ve recently watched this film 3 times since seeing it in the cinema run in high school. Really illuminating article to keep with the theme… this movie connected and scored where To Live and Die in L.A. faltered and missed.

Being from the ATL…appreciate how you called out the shooting locations there… all seared into a local’s memory as architectural/cultural icons new to us in the film’s era… and so simpatico with the stylistic core of the movie.

Humorous aside… made my Millennial from Poland watch one of the three times I did… who simply stated “WTF was that?” afterwards.

Another great piece.