Husbands and Wives

Battlefield mockumentary embedded with modern marriage

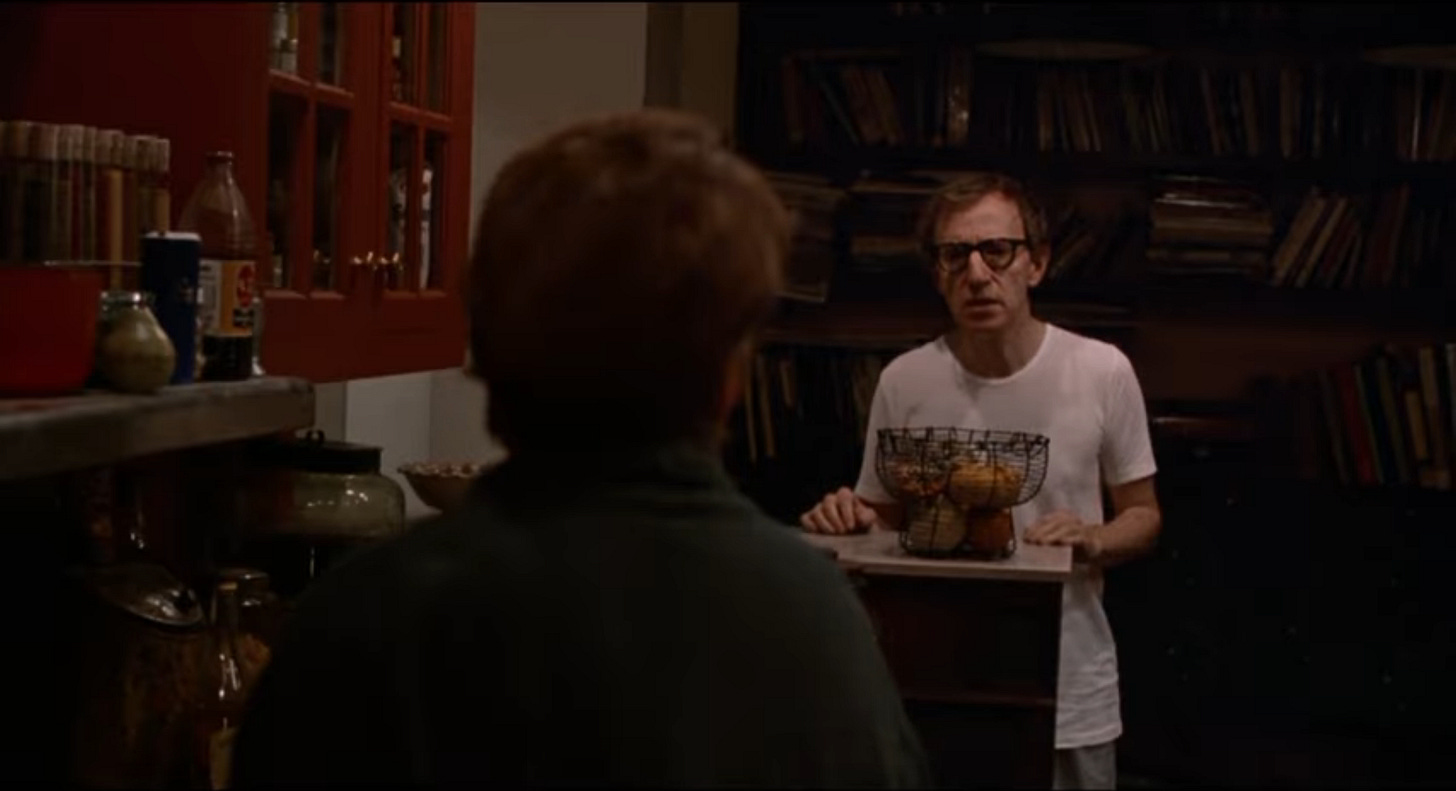

Standup comic/ actor/ writer/ director Woody Allen was born on November 30, 1935 in the Bronx, NY. To celebrate his 90th birthday, Video Days returns to his third decade of work this month with ten films from the master filmmaker.

HUSBANDS AND WIVES (1992) edges the viewer out on a tightrope and keeps us off-balance through most of its 107-minute running time. An examination of four friends in two modern marriages–one couple announcing their separation, the other couple left to question how strong their union is–writer/ director Woody Allen resists driving in the drama lane or the comedy lane, or sticking to a safe speed. Instead, the filmmaker careens between the two roads and crafts one of the most suspenseful, if not most violent, films he’d made up to this point in his career.

Woody Allen had been tinkering with the idea of a film in which content mattered above all else. Rather than capturing the most beautiful light or choreographing the most majestic angle, his camera would follow the actors, the more jarring the look and feel, the better. The most controversial issue facing him when he started pre-production on his twenty-first film was who would finance and distribute it. Allen was granted a reprieve from fulfilling the three-picture deal he’d signed with Orion Pictures in early 1990 due to the financial crisis unraveling the studio, their release of his twentieth film Shadows and Fog looking less likely in the fall of 1991. Allen was quick to walk away from discussing a long term deal with Disney’s Touchstone Pictures, where studio president Jeffrey Katzenberg insisted on input over Allen’s scripts, casting, and on retaining final cut. The filmmaker got closer to reaching an agreement with Twentieth Century Fox before Mike Medavoy, the new chairman of TriStar Pictures, agreed to finance and distribute Allen’s next film, guaranteeing him creative control. Medavoy, former VP of production at United Artists and co-founder of Orion, had been working with Allen since 1974. With his usual collaborators on board–producer Robert Greenhut, director of photography Carlo Di Palma, editor Susan Morse, production designer Santo Loquasto, casting director Juliet Taylor–a cast was assembled.

Australian actor Judy Davis, who’d appeared as the radiant ex-wife of Joe Mantegna’s character in Alice (1990), was cast as Sally Simmons. Despite exhibiting neuroses familiar to viewers of a Woody Allen film, Sally appears to have reached a mutual decision with her husband Jack to separate after a lengthy marriage. Sydney Pollack, director of The Way We Were (1972), Three Days of the Condor (1975), Tootsie (1982) and Out of Africa (1985), was cast as Jack. Pollack, who’d gone by “Syd” and “Sidney” as well as Sydney for television roles in the fifties and sixties, had yet to work as a film actor on a part larger than the harried agent of Dustin Hoffman’s character in Tootsie. Mia Farrow and Woody Allen took the parts of the other couple, Judy and Gabe Roth. Liam Neeson and Emily Lloyd were cast as characters Judy and Gabe are tempted by, a co-worker who Judy initially sets up on a date with Sally, and a 20-year-old student in Gabe’s creative writing class.

Woody Allen Fall Project ’91 commenced filming in November 1991. Emily Lloyd, cast as the female lead in Wish You Were Here (1987) at the age of sixteen and heralded as a rising star, had reeled off performances in Cookie (1989), In Country (1989), Chicago Joe and the Showgirl (1990), Scorchers (1991) and A River Runs Through It (1992). After two weeks of rehearsals and two days of filming, the actor reached what was announced as a mutual decision to exit Allen’s production. (In the coming years, Lloyd would be candid about her struggles with her emotional health, putting an acting career on the backburner in late 1991 to focus on the former). Juliette Lewis, whose breakout performance in Cape Fear (1991) had just opened, was named as Lloyd’s replacement. Securing finance and distribution, or replacing an actor, are among the most difficult problems a filmmaker can solve, but nothing on the books would compare to the public relations nightmare that erupted around Woody Allen, Mia Farrow and Husbands and Wives in mid-August 1992, on the cusp of the film being screened for the closing night of the Toronto Film Festival and TriStar releasing the picture in mid-September.

For starters, the twelve-year civil union between Allen and Farrow had very publicly and very bitterly dissolved. In January, as reported by the New York Times on August 31, Farrow had discovered nude photos of her then 20-year-old adopted daughter Soon Yi Farrow Previn taken by Allen, who’d entered a consensual relationship with the young woman in December, while Husbands and Wives was in production. Allen convened a press conference where he maintained that Soon Yi and he were in love. (The couple would marry in December 1997 and as of 2025, remain married). A custody battle erupted over Allen and Farrow’s adopted children Dylan and Moses, and their biological child Satchel. Connecticut State Police announced they were investigating allegations that Allen had sexually abused the daughter, seven-year-old Dylan. No charges would be filed, no arrests made. The public would be left to pick sides or file their own versions of what might’ve happened. Vanity Fair published a lengthy piece in November 1992 titled “Mia’s Story” that placed readers in her position. Allen continued to write and direct a film a year, working with major stars, while his market as a film actor–DreamWorks Animation cast him as the voice of the lead character in their feature film Antz (1998)--would begin to eclipse Farrow’s demand, even as the audience for Allen’s films continued to recede from the cultural summit they’d held in the 1970s.

The scandal had an immediate impact on the reception of Husbands and Wives. TriStar jettisoned their plans for a platform release starting in five cities on September 23, moving the date up to September 18 and opening the picture wide on 865 screens. While the studio maintained that Husbands and Wives was Allen’s most commercial movie since Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) and supported it with print and television ads, it was withdrawn from the film festival circuit, a press junket which Allen had uncharacteristically shown willingness to participate in scrubbed, and the rest of the cast absolved from promoting the movie. Mia Farrow recused herself from playing the female lead in Allen’s next picture, Diane Keaton replacing her in Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993). Even as critics took the time to address the scandal, their reviews of Husbands and Wives trended very positive. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert gave the film two thumbs up. Siskel prefaced it as “the most talked about movie of the year, and that was before anybody saw it.” He valued the film for “its sharp, edgy portraits of troubled marriages,” and in spite of Judy Davis’ performance, didn’t categorize the new Woody Allen film as a comedy. The critic had to repeat that he liked it, as if such a thing defied logic.

Roger Ebert, who seemed exhausted before even commenting, credited Husbands and Wives as “a thoughtful, penetrating movie.” He likened the "eerie” first ten minutes to a deposition on the headlines he’d been reading for weeks, but once the characters and story asserted themselves, the film worked for him. Vincent Canby of the New York Times and John Hartl of the Seattle Times also filed raves (reviews assigned to female critics were harder to find). Any hope TriStar had that the press would help the film’s commercial reception evaporated. Husbands and Wives opened against the comedies Captain Ron (on 1,414 screens) and Singles (1,073 screens), with Sneakers remaining atop the box office in its second week of release. The following weekend, The Last of the Mohicans debuted atop the charts. Husbands and Wives spent two quiet weekends among the top ten grossing films in the U.S. before disappearing. In his critical write-up for New York Magazine, David Denby headlined his piece “Woody Allen’s Husbands and Wives is a good movie, yet a decade may have to pass before anyone can see it for itself.” As a consolidation, the film was nominated for two Academy Awards: Best Supporting Actress (Judy Davis) and Best Original Screenplay (Woody Allen).

In chronicling two couples in Husbands and Wives–one splitting up, the other factoring whether to stay together—Woody Allen employs a cinéma vérité style. Interludes feature characters confiding to an off-camera interviewer (voiced by Allen’s frequent costume designer, Jeffrey Kurland). Most viewers today will recognize the framing device as seen on the British TV series The Office (2001-2003) and its American counterpunch (2005-2013), but the mockumentary had been perfected long before, by Albert Brooks with his comedy Real Life (1979) and cranked up to 11 by Rob Reiner in his directorial debut, This Is Spinal Tap (1984). Allen uses that toolbox in Husbands and Wives to put us on the front lines with his characters as they probe, attack, retreat and face destruction amid their marriages. It’s an exhilarating drama that qualifies as the most violent film Allen had made up to this point in his career. Far from litigating his relationship with Mia Farrow, Allen passes the ball to Judy Davis, who both on the page and in her performance is a force of nature. Her character certainly does not appear happy, but has grown comfortable being married, and the thought of being single again seems to agitate her to the point the viewer is made nervous, in a way that Davis excels (she was considered a front runner to win an Oscar for Best Supporting Actress, Marisa Tomei an also-ran in a light comedy titled My Cousin Vinny).

Mia Farrow has the tougher role, playing a quietly manipulative person who finds a way to get her way. Whatever stage the off-camera meltdown between Allen and Farrow was at, it’s a credit to Farrow that her performance is consistent through the entire movie. If she looks tired, Allen’s screenplay gives her character every reason to be. Allen again reserves his harshest critique for his male characters, both of whom play with matches and get burnt. Jack turns his attention to dating an aerobic instructor in her twenties named Sam who he assumes will be less flammable and fit easier into his lifestyle. Played by English actor Lysette Anthony (with an American accent), it’s a credit to Allen as a director that far from just posing like the model that Anthony was, her performance has nuance and depth. Rather than being a joke, we feel sorry that Sam ever got involved with Jack and Sally. The casting of Sydney Pollack, a fellow director, as Allen’s friend–as opposed to a handsome actor like Tony Roberts–helps move Husbands and Wives further from a movie and closer to something that feels real. While Allen doesn’t really stake a pessimistic view on modern marriage–suggesting that human beings are too social and maybe a bit too needy to tackle life alone–he does submit a compelling document on relationships taken for granted in the seventies or eighties that were running on fumes by the nineties.

Woody’s cast (from most to least screen time): Mia Farrow, Woody Allen, Judy Davis, Sydney Pollack, Liam Neeson, Juliette Lewis, Lysette Anthony, Timothy Jerome, Ron Rifkin, Christi Conaway, Blythe Danner

Woody’s opening/ closing credits music: “What Is This Thing Called Love,” Leo Reisman and His Orchestra (1930)

Video rental category: Drama

Special interest: Mockumentary