Home Alone

Burglars and booby traps overwhelm Yuletide fantasy

The late writer/ director/ producer John Hughes was born February 18, 1950 in Lansing, Michigan. He’d be celebrating his 75th birthday this month. Video Days kicks off its inaugural month with a retrospective of ten of the filmmaker’s pictures.

HOME ALONE (1990) is a coin with two winning sides: the fear adults have of leaving one of their children behind and the terror kids have of being abandoned. The movie can’t really lose operating from this universal anxiety as an emotional baseline, not with the casting of the extraordinarily kooky Catherine O’Hara as the mom and his star-making performance as a child actor, Macaulay Culkin as the kid. But the filmmakers do short change themselves by trying to pass off foreign currency, in this case, a home invasion and pratfalls from a different movie.

According to his son James, in August 1989 filmmaker John Hughes was on the eve of taking his family on their first European vacation. Hughes was checking off a list of items he didn’t want to leave behind, which included his children. That got Hughes wondering what would happen if he did leave his ten-year-old James home alone. Hughes had captured teenage angst in Sixteen Candles (1984), The Breakfast Club (1985) and Ferris Bueller’s Day Off (1986), which he wrote and directed, and Pretty In Pink (1986) which he wrote and produced, His depiction of modern family in Uncle Buck (1989) had been well-received, particularly its kids, a seven-year-old played by Macaulay Culkin and a five-year-old by Gaby Hoffmann. This gave Hughes the runway to make a movie anchored entirely by a child. Hughes the writer dashed off eight pages of notes and when he returned to Illinois two weeks later, expanded on the premise, cranking out a draft in nine days.

Devoting 1990 to more writing, Hughes the producer sought to hire a director for Home Alone. His choice to helm his script for National Lampoon’s Christmas Vacation (1989) had been Chris Columbus, director of Adventures In Babysitting (1987) and Heartbreak Hotel (1988), grateful for the job after the latter failed commercially and critically. Preparing Christmas Vacation, Columbus attended a meeting with Chevy Chase which the director recalled as being tense, compounded by an even more humiliating followup with the star. With second unit photography underway in Chicago, Columbus capitulated to Hughes that he could not go through with directing Chase. He assumed his directing career was probably over, but a few months later, received a pair of scripts from Hughes–Home Alone and Reach the Rock–asking him to pick the one he wanted to direct. Fascinated by Christmas as the best time of the year and the worst, setting his script for Gremlins (1984) during Yuletide, Columbus identified with Home Alone.

After due diligence of considering other child actors, Columbus cast Macaulay Culkin as Kevin McAllister. Robert DeNiro was seriously considered to play one of the burglars, Harry, but the production was thrilled when Joe Pesci agreed to do the part. Cast as his partner Marv was Daniel Stern, an actor Pesci had befriended on the set of I’m Dancing As Fast As I Can (1982), both playing residents of a mental institution. Stern, narrating and directing episodes television’s The Wonder Years, refused the altered terms of his deal, with Hughes adding two weeks of shooting to Stern’s six-week schedule without an increase in pay. Stern was replaced by Daniel Roebuck, a Chicago actor who’d be featured as one of the U.S. marshals in The Fugitive (1993). The middling chemistry between Pesci and Roebuck in rehearsals led to Hughes luring Stern back by adhering to a six-week work schedule. After scouting the Chicago-area villages of Glencoe, Lake Forest, Wilmette and Winnetka, 671 Lincoln Avenue (which Kevin refers to as “671 Lincoln Boulevard”) in Winnetka was cast as the home, a Georgian-style mansion in red brick with five bedrooms and six full bathrooms.

Three weeks before the start of filming, Warner Bros., then under the regime of co-chiefs Robert Daley and Terry Semel, reached an impasse with Hughes over the budget, refusing to increase it by roughly $700,000 to $14.7 million. The studio made the decision to pull the plug on Home Alone. Hughes reached out to Joe Roth, chairman of Twentieth Century Fox. Roth liked the story, liked the talent, and didn’t have a movie to schedule for Thanksgiving. With financing and distribution locked in from Fox, shooting commenced February 1990. Interiors for the McAllister mansion and the American Airlines plane were shot in the gymnasium of what had been New Trier West High School in Northfield, Illinois, closed in 1984. The flooded basement set was built in the school’s former swimming pool. Shooting also took place at Chicago O’Hare Airport, Hubbard Woods Park (where an outdoor skating rink was built), Trinity United Methodist Church in Wilmette (for the church exterior) and Grace Episcopal Church in Oak Park (the church interior).

The production caught another break when Bruce Broughton, who Columbus had hired to compose the musical score, was delayed completing The Rescuers Down Under, set to open the same day as Home Alone. Columbus contacted Steven Spielberg, who knew John Williams’ agent. The agent delivered a screener to the composer, which Williams loved, agreeing to compose the music. The film’s two Academy Award nominations would be for Best Original Score (John Williams) and Best Original Song (“Somewhere In My Memory,” music by John Williams, lyrics by Leslie Bricusse). Opening November 1990, Home Alone garnered neither critical raves (Chicago film critics Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert turned two thumbs down) or a massive release, opening on 1,202 screens in the U.S. But with nothing else like it on the market and positive word of mouth, many of its screenings were sold out. Home Alone made a once-in-a-century box office run, crowned by U.S. audiences as the #1 grossing film for twelve consecutive weekends and occupying the top ten for another eleven weekends. It finished the highest grossing motion picture of 1990 and by late summer 1991, became the third highest grossing movie of all time.

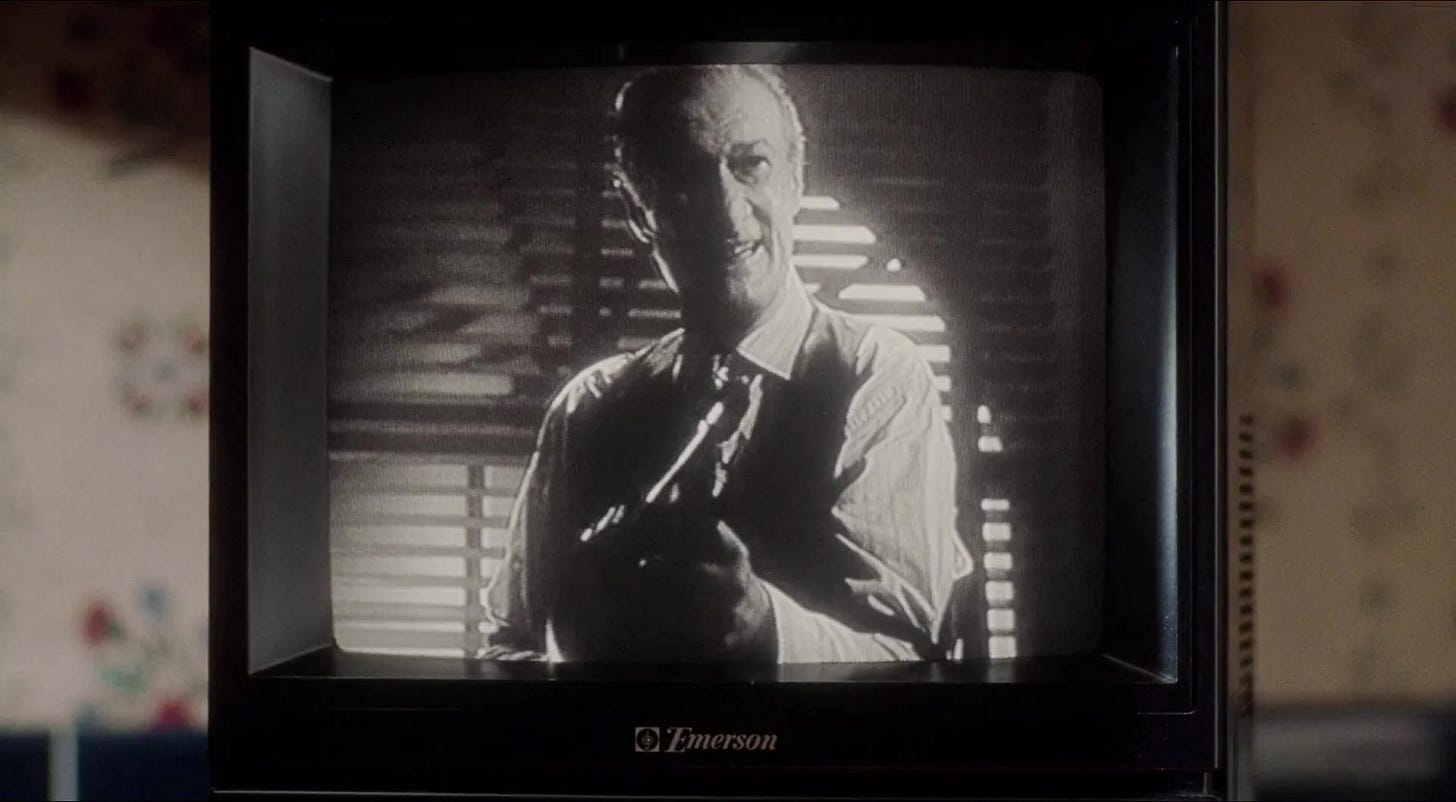

One of the strengths of Home Alone is its wish fulfillment. Most people can relate to wanting a break from being told what to do, or can remember fantasizing about that freedom as a child. It’s a toasty tale for the hectic holidays, when families crowd together and there is even less autonomy. The cast is superlative. Culkin, less precocious than he was in Uncle Buck, shines in his ability to get laughs on his own, particularly with what would become a signature scream, which Columbus doesn’t overdo and gets a laugh every time. O’Hara is perfectly cast as a Yuppie who could both afford five children and abandon one of them at home. The funniest gag is the movie-within-a-movie, Angels With Filthy Souls, a 1940s gangster picture Kevin has been forbidden to watch, but on videotape, replays at top volume to scare people at the door. It’s a testament to the way Hughes wrote this bit, Columbus shot it, and Chicago actor Ralph Foody plays what appears to be a gangster private eye that most viewers accept this is a real movie, woven amongst clips of It’s A Wonderful Life and How the Grinch Stole Christmas.

Considering there was something valuable buried in Home Alone but how overactive and stressful the holidays have become–to the point child abandonment is seen as a solution–what the film absolutely did not need were two bumbling burglars and a farcical home invasion. These feel imported from a kids movie, the type adults typically avoid. While the first hour and twenty minutes of Home Alone are relatable, the slapstick of an eight-year-old repelling burglars, rigging the booby traps he does and rigging them minutes after rushing home doesn’t fit with the nuanced comedy that came before it. Home Alone gets away with feeling much bigger and better than it is by virtue of John Williams, who hadn’t composed music for a comedy since 1941 (1979) and really none prior to that. Williams never scored a film that felt anything short of epic, but the more observant and grounded Home Alone is, the better it is. For those tickled by the Looney Toons elements, recognition is due to stunt coordinator Freddie Hice–who noted that most of the top stuntmen were booked for Days of Thunder (1990) at that time–and the doubles for Pesci and Stern, Troy Brown and Leon Delaney.

Video rental category: Family/ Animated

Special interest: Movie Within A Movie