E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial

First contact meets growing pains in greatest 'Kids on Bikes' movie of all

Video Days is on summer vacation and idling away the afternoons in our treehouse, craving an adventure. Join us in the month of June for five films combining adolescent spirit and a journey.

E.T. THE EXTRA-TERRESTRIAL (1982) doesn’t need reframing to appeal to a wider audience–until Jurassic Park (1993), it held the title of highest grossing movie ever made--but for those who don’t like science fiction pictures or creature features, this is a story about a child and a lost dog. The child thinks they’re rescuing the dog, but it’s the dog who ends up rescuing the child, and its work done, it goes home. If that summary doesn’t pull any emotional chords, the movie is on another level, written, shot, edited and scored to magnificence.

Director Steven Spielberg met Kathleen Kennedy when she was assistant to one of the executive producers of his comedy 1941 (1979): John Milius. Grooming Kennedy for a role with greater responsibility–as his associate on Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981)--Spielberg shared an idea he had for a movie, buried deep within research he’d done on Project Blue Book for Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977), the film Kennedy credited for her inspiration to go into filmmaking. The item that had caught Spielberg’s eye was the so-called Hopkinsville Goblins incident in Kentucky of 1955, in which five adults and nine children claimed their farmhouse had come under siege by otherworldly creatures in the night. Spielberg put Kennedy in charge of developing a script, and she set up a meeting between her boss and John Sayles, whose work-for-hire scripting the Roger Corman pictures Piranha (1978), The Lady In Red (1979) and Battle Beyond the Stars (1980) had funded a serious directorial debut titled Return of the Secaucus 7 (1980). Columbia Pictures not only footed the bill for Sayles to start work on a script, but makeup effects maestro Rick Baker and his crew to begin designing aliens for what was titled Night Skies.

Sayles’ script concerned several insufferable midwesterners–an angry father, religious mother and three kids, the youngest a mute boy–whose farmhouse is attacked by hostile aliens. The invaders included a character dubbed Buddee, a friendly alien who repairs a radio in the garage to signal home for help. The script concluded with the sinister aliens going home and Buddee staying behind to be the mute boy’s friend. Spielberg read Night Skies while up to his elbows in snakes and Nazis making Raiders of the Lost Ark in England and Tunisia. He not only wanted to direct a much more benevolent movie next, but no longer believed that aliens would cross the universe to terrorize mankind; observe perhaps, or befriend, but not threaten. Spielberg wanted to direct a musical, and had not only employed Gary David Goldberg to write what they were calling Reel To Reel, but flew the writer/ producer to London to work with him on a script. As for Night Skies, Spielberg told Kennedy that the final scene in the script–an alien is left behind and befriends a lonely boy–was much closer to something he could see himself directing. Realizing this would require a new screenwriter to pen a completely different script, Kennedy suggested someone who was already with them in North Africa.

Spielberg knew Melissa Mathison as Harrison Ford’s girlfriend, but she’d started her career as babysitter to Francis Coppola’s children when she was 12 years old. Coppola later hired Mathison as a location assistant on The Godfather, Part II (1974) and his executive assistant on Apocalypse Now (1979), which is how she’d met Ford, in 1976. Coppola further encouraged Mathison, hiring her to work with screenwriter Jeanne Rosenberg on a draft of a picture he was producing: The Black Stallion (1979), a story about the relationship between a boy and a horse marooned on an island. Spielberg not only loved the movie, but like Kennedy, recognized similarities to the science fiction/ fantasy he was noodling. The director pitched Mathison a beginning, middle and ending to the kids meet extraterrestrial story he’d sketched out, but the screenwriter had struggled finishing an adaptation of a book she’d optioned, and didn’t feel she was right for the job. Kennedy and Ford both campaigned to change her mind, which Mathison did. On what seemed like a separate track, Spielberg had wanted to direct a movie about childhood, inspired by his youth growing up in Scottsdale, Arizona in a family split by divorce. No less than François Truffaut, director of The 400 Blows (1959) and Small Change (1976) who played Lacombe in CE3K, had encouraged Spielberg that rather than more action movies, he needed to make one about childhood.

After he’d completed CE3K, Spielberg commissioned a screenplay from his protégés Robert Zemeckis & Bob Gale. Spielberg’s main note had been that the story should concern nerds versus jocks. Titled After School, the draft by “the Bobs” leaned toward realism, like The Bad News Bears (1976), with seventh graders cursing like real kids, hardly the nostalgic tale Spielberg had in mind. What he was referring to as A Boy’s Life seemed like a way to blend a benevolent science fiction movie about a lonely extraterrestrial with a dramatic comedy about earthbound adolescence. When everyone was back in the States in October 1980–Spielberg editing Raiders of the Lost Ark at his beach house in Marina Del Rey, Kennedy agreeing she was ready to produce Spielberg’s next film with him, Mathison working out of an office in Hollywood–they began story meetings, Mathison traveling to Marina Del Rey once a week to take notes or recordings from Spielberg and return to her office to write. Using Harrison Ford’s sons Benjamin and Willard and their friends as subject matter experts, Mathison had asked what powers the boys would want a benevolent extraterrestrial to wield. More than one mentioned telepathy, but to Mathison’s surprise, the consensus was that an alien would have healing powers, not necessarily to reanimate the dead, but to take away the aches or pains of life.

Mathison’s work took a different path than a male screenwriter might have with the same material, whether he had children or not, which Spielberg did not at the time. For example, when Spielberg proposed that E.T. would touch down at a used car lot, Mathison countered that it should be a forest, where faeries of myth resided. Spielberg loved the idea that E.T. would share a psychic link with the boy, Elliott, who’d experience whatever emotions the extraterrestrial was feeling. After eight weeks of meeting and writing, Mathison delivered to Spielberg a first draft of E.T. and Me. Spielberg was ecstatic, exclaiming to Kennedy it was not only the best first draft he’d ever read, but one he felt he could shoot tomorrow. The characters and story dialed in, E.T. itself had not begun to be addressed. Spielberg pitched Rick Baker with his new approach to Night Skies, explaining to the makeup artist that instead of seven compelling characters, he needed a single special one. In addition to the reduction in scale, Baker realized that Spielberg no longer needed someone to design creatures for a horror thriller, but a Walt Disney film, and they agreed to work together on something in the future, which they did, executive producer Spielberg commissioning Baker for Men In Black (1997) and its sequels.

The filmmaker approached special effects makeup artist Stan Winston at the same time he did Carlo Rambaldi, the latter of which built the alien as seen in CE3K. Winston was game for handling both the conceptual and mechanical needs of the character, as he would the dinosaurs in Jurassic Park and its sequels, and uninterested in partnering with Rambaldi, bowed out. Spielberg brought in storyboard artist Ed Verreaux, a production illustrator on Raiders of the Lost Ark, to work with Rambaldi sketching designs for E.T. The director proposed an off-putting, even ugly, visitor, yet one who would not be frightening. Using the faces of Albert Einstein, Ernest Hemingway and Carl Sandburg, old men Spielberg found both wise and sad, sketches Spielberg approved led to a clay model. Conceptual artist Ralph McQuarrie of Star Wars took a pass at the design before it was finalized. Armed with a script, sketches and a clay model of E.T., Spielberg let Columbia Pictures president Frank Price in on his plan to cancel Night Skies and direct an entirely new picture about alien visitation. The studio liked Mathison’s screenplay, but concluded that Spielberg’s vision for a Walt Disney film would appeal mostly to children, unlike a project that the studio was developing titled Starman with producer Michael Douglas they thought had broader commercial appeal. Choosing between the two, Columbia went with Starman and placed E.T. and Me in turnaround.

Spielberg put a call in to Sid Sheinberg, president of Universal Pictures, who as much as anyone, the director considered his mentor, having plucked Spielberg from obscurity based on his student short Amblin’ (1968) and signing him to a seven-year contract to direct television for MCA/ Universal at a rate of $300/week. Spielberg never forgot the offer, and intended to honor his contract for Jaws (1975), which had stipulated two future pictures for Universal if both parties could agree on them. Sheinberg had passed on Reel To Reel, but agreed to pick E.T. and Me up from Columbia at a production budget Spielberg and Kennedy promised would be $10 million. It would be made in tandem with a picture Spielberg was making at MGM titled Poltergeist (1982). Directed by Tobe Hooper, Spielberg had not only written most of the haunted house thriller, but approved the cast, storyboarded the shots, and whether because he thought he needed to or felt he wanted to, was on the set nearly every day of production, a division of labor which not only created a furor within the Director’s Guild of America but unfriendly coverage in the press. Spielberg’s involvement in Poltergeist pushed E.T. and Me off its June 1981 start date by three months until the former could wrap. Drew Barrymore had auditioned for the role of Carol Anne in Poltergeist and though the six-year-old’s energy had been a little too much for the character Spielberg had in mind, she was right for Gertie in E.T. Fourteen-year-old Robert Macnaughton was working on a play in New York when he’d been invited to Los Angeles to audition for his own haunted house thriller, The Entity (1982), and though he didn’t get the part, was notified that Mike Fenton & Jane Feinberg and Marci Liroff were casting a new movie for Spielberg.

Another boy had so aced his audition that he’d been penciled in for the role of Elliott, but during a group rehearsal at Melissa Mathison’s house in which the boys’ chemistry was tested over a game of Dungeons & Dragons, the filmmakers observed that none of the other cast members much liked Elliott, the actor coming off as bossy among other kids. With less than a month to go before shooting, Spielberg received a recommendation from production designer Jack Fisk, who’d directed a movie starring his wife Sissy Spacek titled Raggedy Man (1981) about a war widow raising two boys in a desolate town in Texas. One of the boys–a nine-year-old Texan named Henry Thomas–came to L.A. to read a page or two and participate in an improv with Fenton and Spielberg in which Elliott reacts to a federal agent taking E.T. away. Thomas’ improvisation won him the part. In the two adult roles, Dee Wallace and Peter Coyote had both auditioned for Spielberg on shows they didn’t get. Wallace had met the producer for a role in Used Cars (1980), while Coyote had auditioned for the role of Indiana Jones. Coyote was so nervous in his big meeting with George Lucas and Steven Spielberg that he’d knocked over a lighting stand. Spielberg later acknowledged that if Raiders of the Lost Ark had been a comedy, the gig would’ve been Coyote’s, but his awkwardness was perfect for E.T. and Me.

One of the reasons Spielberg had wanted E.T. to have a telescopic neck was to give the illusion that the alien wasn’t another man inside a styrofoam suit. The impossibility of creating the performance called for in the script with the animatronic technology of the day–E.T. waddling and even running–sank in, and several performers were utilized for shots in which E.T. needed to move realistically. Most of these were performed by a little person named Pat Bilon, while another small performer, Tamara De Treaux, was used for a more rigorous shot in which E.T. scales the ramp of his spaceship. The character’s movements in the kitchen sequence were done by a boy born without legs named Matthew De Merritt, who could walk on his hands. While they were able to get E.T.’s eyes right employing a preeminent designer of glass eyes, Spielberg was unsatisfied with the puppet’s arms or hands when they moved. A mime named Caprice Rothe, credited as “E.T. movement coordinator,” was cast and drew strong praise from the director for the instinctive performance she gave with her hands.

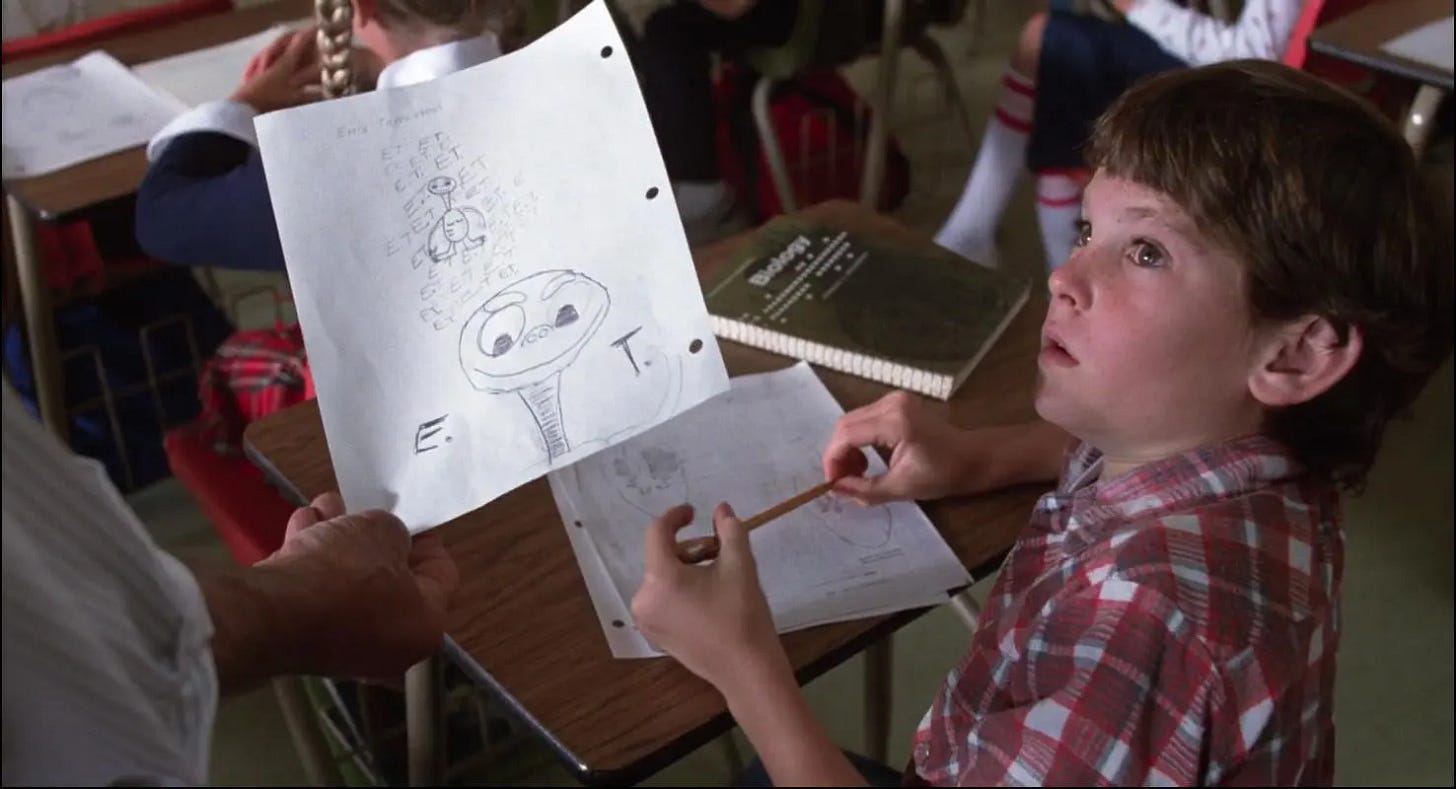

E.T. and Me commenced a 65-day shooting schedule in September 1981 in (much different times) the Los Angeles area. It operated under the code name A Boy’s Life, the script (the WGA awarded sole writing credit to Melissa Mathison) and even its title kept under wraps, the filmmakers wary of a rip-off beating them into theaters. Spielberg even declined shooting the picture on the Universal Studios lot to avoid anyone in the industry getting too close a look at what he was doing next. The first two days were spent at Culver City High School for the sequence set at Elliott’s school. 11 days in the San Fernando Valley suburbs of Northridge and Tujunga were utilized for exteriors of Elliott’s house or neighborhood, including the climactic bike chase. The bulk of the shoot (42 days) took place on sound stages at Laird International Studios in Culver City. Elliott, Gertie and Mary’s bedrooms, the first level of their house, their backyard and E.T.’s landing site were filmed adjacent to where episodes of Batman or Star Trek had been spoofed in the 1960s. An additional six days were required near Crescent City for exteriors requiring a living forest.

For the voice of E.T., Spielberg admired the low, husky inflection of Debra Winger, who he’d penciled in for the female lead in his remake of A Guy Named Joe. Visiting the Northridge set on the day the Halloween scene was shot, Winger not only agreed to be painted in zombie makeup and carry a poodle for an uncredited cameo, but handed a tape recorder by Spielberg, recorded E.T.’s dialogue. The director would use Winger’s voice in the temp track. For the finished product, sound designer Ben Burtt had stumbled onto a 66-year-old woman named Pat Welsh purchasing (in much different times) film in a San Anselmo photo processing shop a block from Burtt’s studio in Marin County. He asked her to audition, drawn by a voice that was neither conventionally female or male. Burtt would lower Welsh’s pitch electronically, and blend it with animal breathing he’d recorded. Rounding out the actors who’d participate in the film were Harrison Ford and Melissa Mathison, who Spielberg cast as Elliott’s smug principal and a pissed off school nurse. Like most of the adults in the picture, they were shot from the waist down, over the shoulder or in silhouette, but both scenes at the school–though visually witty–were dropped by editor Carol Littleton and Spielberg for simply not advancing the story enough.

Retitled E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Spielberg knew watching his first assembly that it was his best work as a director. As a producer, he couldn’t imagine adults would be interested in the film, designating its appeal to children who’d typically enjoy Disney fare like Escape To Witch Mountain (1975) or its sequel, a calculus that had been shared by Columbia. Ironically, this was the same audience George Lucas had predicted Star Wars (1977) would be limited to. Spielberg didn’t want to share E.T. with executives at Universal until it had been scored by John Williams, color timed and dialed in for a test audience. He invited MCA chairman Lew Wasserman and Universal Pictures president Sid Sheinberg to attend the first test screening of E.T. with him, Mathison and Kennedy in Houston, Texas in May 1982. Spielberg and Sheinberg later described the screening as a quasi-religious experience, with rapturous audience members giving the picture a standing ovation. As a measure of how it might play to an adult crowd, Spielberg made his first ever appearance at the Cannes Film Festival later that month to screen E.T. out of competition. This time, it received a fifteen-minute standing ovation. Universal proposed releasing E.T. in 1,600 theaters amid the strongest competition of the summer the following month. No movie except Conan the Barbarian (1982) or Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982) was opening in 1,600 theaters, and Spielberg tempered the release back to 1,100 theaters.

Opening June 11, 1982, E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial was perhaps the best reviewed film of the year, with few naysayers among newspaper critics. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert gave it two unequivocal thumbs up. Siskel credited the film for reviving the sort of love reserved for pictures about boys and their dogs, playing as sweet and timeless. Ebert went further in his praise, comparing the experience of watching E.T. with what people must’ve felt watching The Wizard of Oz (1939) for the first time, introduced to a magical movie that would stick around as a classic. Both critics would rank E.T. #3 on their year-end list of 1982’s ten best films. Writing in the New Yorker, Pauline Kael would comment, “When the children get to know E.T., his sounds are almost the best part of the picture. His voice is ancient and otherworldly but friendly, humorous. And this scaly, wrinkled little man with huge, wide-apart, soulful eyes and a jack-in-the-box neck has been so fully created that he’s a friend to us, too; when he speaks of his longing to go home, the audience becomes as mournful as Ellott. Spielberg has earned the tears that some people in the audience–and not just children–shed.”

E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial opened during what many have referred to since as the greatest summer movie season ever. It was in immediate competition with Star Trek II and Poltergeist in their second weekend of release (Spielberg referred to Poltergeist as representing all his fears of suburbia, E.T. his love) and Rocky III in its third weekend. In an unprecedented box office run, Spielberg’s new movie would notch the #1 or #2 spots among the top ten grossing films in the U.S. for all but four weekends through post-Thanksgiving, in first or second place for twenty-two of its first twenty-six weekends in release. Some theaters kept the movie booked for nearly a year. By that time, E.T. had passed Star Wars as the highest grossing motion picture of all time. With Columbia due to receive 5% of the film’s net profits, Frank Price joked that his studio made more money not financing or distributing E.T. than most of the pictures it did that year. Its massive popularity did carry one small regret for Spielberg based on feedback from family groups. The filmmaker regretted federal agents in the film brandishing firearms as a deterrent to the kids, vowing during the film’s fifteenth anniversary in 1996 that if given the opportunity to tweak E.T. digitally, he’d remove the guns. Having never used CGI to redo one of his films, Spielberg took Universal up on their offer for the 20th anniversary re-release of E.T.

Arriving in 2002, the “Anniversary Edition” of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial on DVD featured 56 digital changes (Industrial Light & Magic improving the compositing or detail in shots, like E.T. now hopping through the forest to escape capture instead of being pulled along on what is clearly a track), two new scenes, one change in audio and two changes for violence (the aforementioned firearms) resulting in a new running time of 114 minutes, the theatrical version clocking in at 109 minutes. To his credit, Spielberg did insist that unlike George Lucas’s special editions of Star Wars, the DVD be released as a 2-disc set, the theatrical version available along with the digitally enhanced one. Even in a time before social media, Spielberg’s decision to erase guns from E.T. drew a sharp rebuke. Participating in a conversation with Harrison Ford and the Los Angeles Times for the 30th anniversary of Raiders of the Lost Ark in 2011, Spielberg admitted that he couldn’t resist using CGI to do facial enhancements on E.T. that Carlo Rambaldi couldn’t achieve with the technology of the time, but he now regretted robbing people of their memories of E.T. and pledged he’d never digitally touch up one of his classic films again.

One of the delights of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial is that it validates for those of us who believe we’re not alone in the universe that intelligent life is not only out there, but that it could visit us and remain anonymous because most adults would be too busy to notice. In its funniest scene, Mary is so preoccupied–unloading groceries, tending to Gertie, taking a call from Ellott’s school–that she doesn’t see an alien waddling through her kitchen (Drew Barrymore’s line when Dee Wallace hits E.T. with the refrigerator door, “Here he is. The man from the moon, but I think you've killed him already,” is hysterical). For all the criticism Steven Spielberg accepted for his comedy 1941 being unfunny, there are laugh out loud moments throughout all of his action/ adventure films, and operating with material that he could relate to from the inside out, E.T. tickles the funny bone more effortlessly than any film he’d made before or since. Its young cast–including future Playboy Playmate Erika Eleniak, who memorably popped out of a cake in Under Siege (1992)--are directed in a way that they understand who their characters are, Mathison and Spielberg knowing what each child’s relationship would be and what they’d be doing from scene to scene as a real child, not a movie character acting out a plot. Specifically, E.T. is made possible by the children of one particular generation, Generation X, who grew up unmonitored. Today’s children exist under such a microscope that Elliott’s encounters with E.T. would be recorded by security cameras, the movie proceeding very differently, if at all.

Until the moment the government comes for E.T., almost all the adults are shot from the waist down, over the shoulder, or at a distance, like the Warner Bros. or MGM cartoon shorts of the ‘50s, a bold choice for a live-action film. In a child’s world, grown-ups only appear in close-up if they’ve passed certain tests, like Mary, who’s hanging on by a pretty loose thread, and once he introduces himself, Keys (Peter Coyote), who hasn’t lost his childlike innocence either. In this way, E.T. remains subtly anchored in a child’s point of view. Comic moments rooted in reality by Spielberg and his director of photography Allen Daviau, as well as wonderful pantomime by Caprice Rothe performing E.T’s arms and hands, are shed as the film shifts into another gear, an emotional one in which a child adopts an animal, protects it, nurses it back to health with love, but then has to release it. Those who made it through Disney’s Old Yeller (1957) without tearing up will be vulnerable to the beauty of Melissa Mathison’s chart and Steven Spielberg’s orchestration. The last twenty minutes of E.T. are up there with the best of anything ever put on film–magic, excitement, joy–with a musical score that ranks as the most powerful John Williams composed. As the undefeated champion of the “Kids on Bikes” movie, it launched the entire series run of Stranger Things on Netflix, Millie Bobby Brown more or less playing an E.T. who bike-riding children in 1980s suburbia adopt. The original has no peers.

Video rental category: Family/ Animated

Special interest: Kids on Bikes