Dangerous Liaisons

Hurried and largely miscast adaptation of play takes off in final moments

Video Days is Mad About Michelle in the month of April, with ten films starring leading lady Michelle Pfeiffer, born April 29, 1958 in Santa Ana, California and celebrating her 67th birthday this month.

DANGEROUS LIAISONS (1988) is a 1930s movie updated with 1980s moral clemency. Like so many pictures of the Golden Age of Hollywood, it’s based on a play, unfolding as a series of conversations, as if limited by the stage or by the recording equipment of the time. It’s a costume drama, recalling Bette Davis pictures like Jezebel (1937) or The Private Lives of Elizabeth and Essex (1939), based on plays. It also feels hurriedly assembled at a price, just like the studio pictures of old. It’s the inferior of two competing versions of the same material released a year apart, but like a Bette Davis film, trades on insidious wit, with a leading lady capable of delivering a withering line.

Playwright/ screenwriter Christopher Hampton was exposed to Les liaisons dangereuses at the age of thirteen, courtesy of the 1959 film of the same name directed by Roger Vadim and starring Jeanne Moreau in what was fashioned as a contemporary version of the 1782 novel by Choderlos de Laclos. Hampton, a French and German scholar, read the book while a student at Oxford University, and it inspired him to write a paper in which he contended that the best writers of pre-revolutionary France were those trafficking in what was then considered pornography. Enthralled by Laclos’ ability to craft an exciting tale–in which two scheming aristocrats, Madame de Merteuil and Vicomte de Valmont, ruin lives for sport–Hampton considered the novel to be one of the most sophisticated treatments on the battle of the sexes. In 1976, when the National Theatre moved from the Old Vic to London’s South Bank, a call went out for new plays. Hampton suggested a stage version of Les liaisons dangereuses. The literary department run by director John Russell Brown didn’t see a way to make the book work as a play, its story unfolding as a multitude of private letters.

Eight years later, Hampton sold an up-and-coming director with the Royal Shakespeare Company on his idea. Directed by Howard Davies, Les liaisons dangereuses, opened in September 1985 at the Other Place, a black box theater in Stratford-upon-Avon. Lindsay Duncan was cast as Merteuil and as Valmont, Alan Rickman. Popular demand shifted the play to the Pit in London, where it won several theatrical awards, before it moved to the West End in October 1986. Six months later, Duncan and Rickman would cross the pond to launch the play on Broadway, at the Music Box Theatre in New York. Nominated for seven Tony Awards, Les liaisons dangereuses saw its prestige clipped when it garnered zero awards. When time came to replace the British cast with an American one, Glenn Close, who’d read the novel as a young actor, expressed interest in playing Merteuil. Instead, the play ended its twenty-week New York run in September 1987, producers unable to finance an American cast led by Close, who wasn’t considered much of a box office draw. Two weeks later, the film Fatal Attraction, starring Michael Douglas and Glenn Close, opened #1 at the U.S. box office, holding that spot and the national zeitgeist for eight weeks.

Producer Norma Francis Heyman, who’d worked with Christopher Hampton when she’d commissioned him to adapt the Graham Greene novel The Honorary Consul, released as Beyond the Limit (1983) with Michael Caine, Richard Gere and Bob Hoskins, found a partner in Lorimar Telepictures, the company responsible for the prime time soap operas Dallas, Knot’s Landing and Falcon Crest. Lorimar paid $400,000 for the film rights to Les liaisons dangereuses. When asked why he’d bankroll something like that, CEO Bernie Brillstein would quip, “It’s Dallas with a French accent.” In another unorthodox move, Lorimar paired Norma Heyman with Hank Moonjean, a prolific American assistant director in the fifties and sixties who’d segued into a producing career in the seventies on a handful of Burt Reynolds pictures, most recently Sharky’s Machine (1981) and the noxious NASCAR comedy Stroker Ace (1983). The producers faced a major obstacle in that two-time Academy Award winning director Miloš Forman was developing a film version of the Choderlos de Laclos novel as his follow-up to Amadeus (1984).

Rather than compete against him, the producers offered Forman the opportunity to direct their adaptation. Having seen the play in London, the filmmaker had no interest in directing that version of the tale, choosing to work with his own writer, Jean-Claude Carrière, on a cinematic version of what he remembered of Les liaisons dangereuses, which he’d also read as a university student. Forman would title his version Valmont. Racing ahead on what would be titled Dangerous Liaisons, the producers tasked Christopher Hampton with three weeks in which to adapt a script. Stephen Frears, who’d directed an adaptation of Hampton’s play Able’s Will as a BBC2 Play of the Week in 1977 and only a handful of low budget British films, received a copy of the script hand delivered by the playwright on January 1. Two months later, Glenn Close, John Malkovich, Michelle Pfeiffer, Uma Thurman, Keanu Reeves and Swoosie Kurtz were announced as the cast with Frears directing. Lorimar greenlit the project in what became one of the company’s last creative decisions. The next day, they approved their sale to Warner Communications for $700 million in stock, with Warner taking on $600 million in Lorimar’s debt, including their $14 million production of Dangerous Liaisons.

Lorimar’s stipulations were that the cast of Dangerous Liaisons not be recycled from the stage play and that the film beat the rival Valmont, which was going before cameras in August 1988, into theaters. Shooting commenced in late May 1988 in France. Costume designer James Acheson and production designer Stuart Craig were given three and a half weeks to research the film’s wardrobe and sets. In order to shoot the film in ten weeks and have it in theaters in December 1988 for awards consideration, locations were limited to those that could be found within one hour of Paris. As they raced to complete the film, the filmmakers had some concern that Warner Bros. might consider their movie a rounding error and choose not to release it, but when Dangerous Liaisons opened over Christmas in limited release, the studio supported it with a strong marketing push.

Reviews were mixed. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert split, Siskel admitting the ending was compelling, but the film was slow-moving. Ebert agreed about the pace, which had been a criticism of the two-and-a-half hour play, but offered that in the right frame of mind, the film was sophisticated. To the surprise of many, Dangerous Liaisons received seven Academy Award nominations, including Best Picture for Norma Heyman and Hank Moonjean. After the awards telecast–in which Christopher Hampton, James Acheson, and Stuart Craig (and set decorator Gérard James) won Oscars–Warner Bros. expanded the film’s release to 762 theaters. Dangerous Liaisons would spend a total of four weeks among the top ten grossing films, a fair commercial showing considering its budget. Arriving in theaters in November 1989 at twice the cost, Valmont, with unknowns Annette Bening as Merteuil, Colin Firth as Valmont, and Meg Tilly, Fairuza Balk and Henry Thomas, drew better reviews, but was ignored by audiences.

Though it was first out of the gate and didn’t suffer in comparison at the time, Dangerous Liaisons doesn’t hold a candle to Valmont. Miloš Forman’s take on the material is not only visually splendid, but compared to those in Christopher Hampton’s stage play, its characters are younger, coming across as more randy and less Machiavellian, which is its own form of cruelty, the callousness in which nature wastes youth on the young. Valmont is a more sensual film too, though despite being financed with European money, not as dark as this American-made version. Taken on its own, Dangerous Liaisons is often delightful in the way it calls back to the Golden Age of Hollywood. Except for being in color and having end credits, much of the film is punctuated like one produced in the 1930s. Characters enter rooms at the beginning of scenes and often exit then when the scene is over. George Fenton, who composed the music for The Company of Wolves (1985) and was starting on a prolific musical career in film and television, turns in a serviceable score that promptly moves the action from scene to scene.

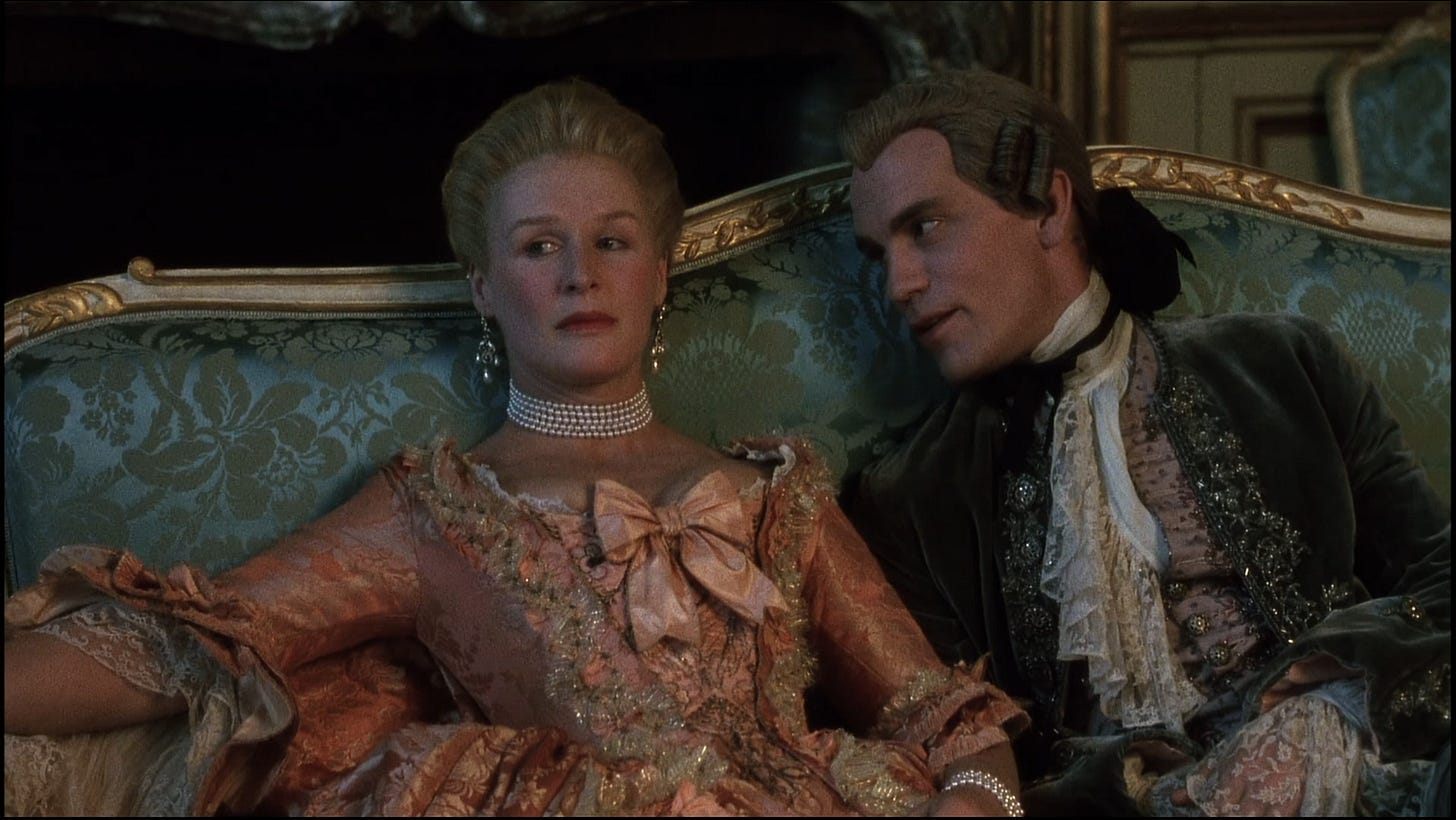

In Hampton’s play, words are not only currency, but filed and used as weapons. John Malkovich’s portrayal of Valmont is where this combative quality had the most opportunity to flourish, but other than his character’s adversarial relationship with Madame de Volanges (Swoosie Kurtz, the most overbearingly American in a cast full of them), the film isn’t nearly as droll as it could’ve been if writing had more time to work on the script with directing. Characters come across as lazy and bored instead of rebellious and combative. The casting is a C+. Glenn Close is far less formidable as Merteuil than she would’ve been as Madame de Volanges. As a femme fatale who yanks Valmont to the end of his rope, Merteuil was the perfect role for an otherworldly presence like Michelle Pfeiffer, not someone as grounded in the 20th century as Close. Malkovich seems on loan from a Hitchcock thriller, his portrayal of Valmont vile and creepy rather than seductive. He’s an effective villain, but an obvious one. The less said of Keanu Reeves as a music instructor in 18th century France, the better. Only Uma Thurman, wonderful as an intellectual and emotional child in the body of a budding superwoman, stands out among the cast. The final scene and the closing moments are far and away the strongest in the picture, suggesting a story that starts way too soon, employing what is backstory as its main story.

Video rental category: Drama

Special interest: Femme Fatale

Oh well, I never saw either Dangerous Liaisons, or Valmont, but I always enjoy your research and analytical opinion… As always, Joe, great job! Peace! CPZ