Clue at 40

Board games meet stage plays in riotous, breakneck farce

CLUE (1985) is to movies what a World Series-winning roster is to baseball. We might not love the team, or even care for the sport, but to finish where this group does is elite. Whether that means Clue should be crowned the best film of 1985 isn’t as final as the result of a seven-game playoff series, but it is one of the funniest and the most crackerjack movie farces. Based on the classic board game Cluedo (published as Clue in the U.S.), it even succeeds as a compelling mystery, and not only holds up under repeated viewings, but improves with them.

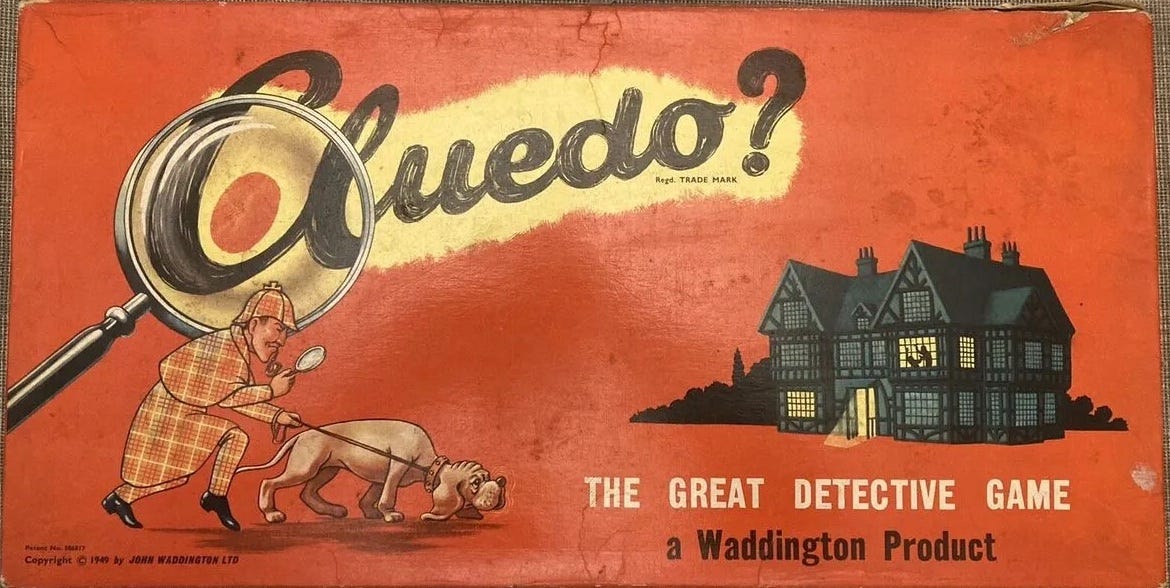

Anthony Pratt was born in 1903, in the Balsall Heath neighborhood of Birmingham, U.K. Driven by a love for music, he left school in his teens, and would earn a living playing piano in hotels or aboard ocean liners. Pratt was a book lover, with crime, philosophy, and psychology among his reading interests. Between world wars, many of the English like him enjoyed convening at each other’s houses on weekends for parties. Among the popular parlor games was Murder, in which a secretly selected murderer would “kill” players in a dim room by winking at them, victims dramatically going to their “deaths” while the other players had to catch the perpetrator (there were variations on the game, but “murder” was a recurring theme). In 1939, most social gatherings were canceled due to war, with Birmingham bombed more heavily than any city in England after London and Liverpool. Pratt went to work at a munitions factory by day and did his patriotic duty as a firewatcher by night. Like most, he began to miss a social life. A neighbor over his garden fence, Geoffrey Bull, had patented a board game titled Buccaneer, achieving modest success selling the publishing rights to Waddington’s, a playing card manufacturer headquartered in Leeds. Following suit, Anthony Pratt and his wife Elva Rosalie Pratt (née Hill) invented a board game they called Murder. The object was to not only determine who among ten characters–Col. Yellow, Miss Scarlet, Nurse White, Rev. Green, Prof. Plum, Mrs. Silver, Dr. Black, Mr. Brown, Mr. Gold, Miss Grey–was a murderer, but where and with what as a weapon.

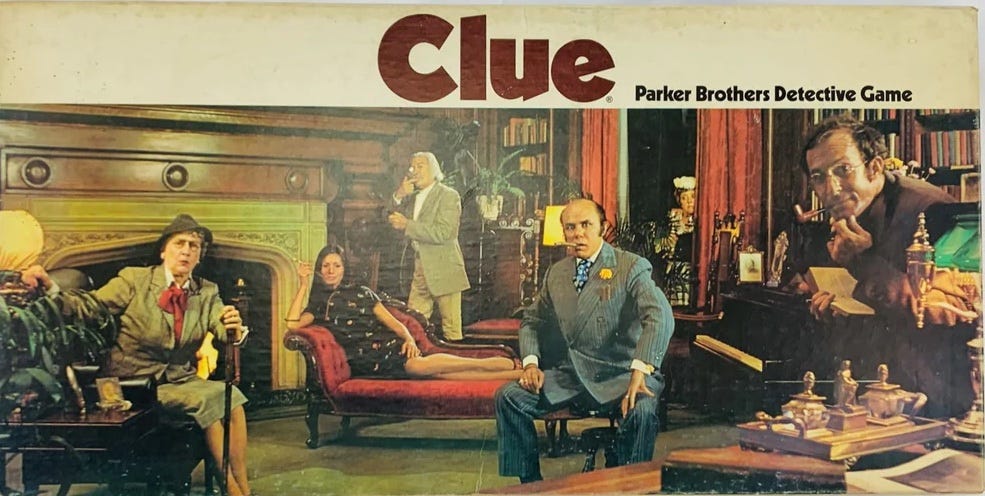

On a board which Elva Pratt designed, players moved tokens around a mansion with ten rooms. In Murder, there were nine weapons: revolver, rope, dagger, cudgel, axe, poker, hypodermic needle, bottle of poison, bomb. Anthony Pratt’s correspondence with Victor Hugo Watson, managing director of Waddington’s, resulted in great interest. Watson made suggestions– changing Col. Yellow to Col. Mustard to avoid the perception he might be a coward, substituting a candlestick for a bomb, a lead pipe for a syringe–and struck a deal to publish the game. 1945 ended up being one of the worst years of the 20th century to manufacture a board game, but what was now titled Cluedo reached shelves in 1949, “Cluedo” a play on the Latin word “Ludo” for “play.” The U.S. publisher, Parker Brothers, simplified this to Clue. In 1953, Pratt made the decision to sell foreign rights to Waddington’s for £5,000, continuing to receive a 5% royalty for each game sold in the U.K. He’d submitted prototypes for two more games to his publisher–one in which players seek buried treasure, the other a gold mine–without success. When Pratt’s patent for Cluedo expired in 1966, checks stopped coming. The game inventor would go to work as a clerk in a solicitor’s office. By 1985, the board game he and his wife invented would be the fourth best seller in the U.S., formerly third behind Monopoly and Scrabble until the arrival of Trivial Pursuit. Clue was selling 750,000 copies a year, few gaming shelves without it.

The genesis for a movie based on Clue was producer Debra Hill, who by the age of thirty had solely produced the most profitable independent film up until that time, Halloween (1978), which she also co-wrote with the director, John Carpenter. Preparing to reteam with Carpenter as his producer and co-writer on The Fog (1980), Hill wasn’t interested in working strictly in the horror genre. She had the novel idea that a board game she’d played as a child might make a successful movie too. Commenting to Bob Thomas of the Associated Press in July 1985, Hill stated, “When I was growing up, I always liked Clue better than Monopoly, which seemed to be just buying and selling. I liked the thinking part of Clue, and I knew that a lot of people had played it–and still play it. When I approached the Parker Brothers people about making a movie of the game, they said nobody had ever asked them.” Starting in 1979, Hill’s pitch didn’t immediately land with the major studios. It was a young development executive for producer Peter Guber named Lynda Obst who could see Clue being adapted into a film, and she sold the idea to her boss. As the former president of Columbia Pictures and the chairman of Casablanca Record and Filmworks, Guber’s track record had won him the job of running PolyGram Pictures, the new film and television division of PolyGram Group. To serve as a co-owner and co-managing director, Guber had brought along his friend Jon Peters, a former hairdresser and boyfriend of Barbra Streisand who’d produced A Star Is Born (1976) and The Main Event (1979) with the superstar. Guber and Peters had secured a development deal with Universal Pictures, which agreed to front them the money to develop a feature film from Clue.

Hill and Obst traveled to England to purchase film rights to Clue from Waddington’s (U.S. toy manufacturer Hasbro would acquire the company in 1994, three years after Hasbro would also acquire Parker Brothers). Continuing to think differently, it was Hill’s idea that just as each play of the game ended with a different murderer, most theaters screening the film could play a different ending, four endings total, with three fourths of the prints shipped with a different one. Waddington’s granted Hill and Obst permission to move ahead without even charging them a licensing fee, accepting payment in lieu of profit participation if and when a movie went into production. Their only stipulations were that the title carry a registered trademark symbol (Clue®) and that the film be devoid of profanity. In October 1980, the Hollywood Reporter announced that Debra Hill had obtained the film rights. Needing a writer, she would base her search in England, where Cluedo was invented and literary murder was one of the country’s primary exports, Arthur Conan Doyle, Agatha Christie and an aisle of British authors writing and basing their whodunits in Great Britain. The challenge for a screenwriter was more than simply fleshing out the game pieces–in the U.S., the characters had been honed down to Col. Mustard, Miss Scarlet, Mrs. White, Mr. Green, Prof. Plum and Mrs. Peacock–but to write a coherent mystery that would sustain itself no matter which of four different endings were plugged in.

The first screenwriter Hill commissioned was playwright Alan Ayckbourn, who for a time was second only to William Shakespeare in terms of mass appeal on the British stage, but who never got very far in a draft of Clue. Later in 1981, author P.D. James attempted to take on the challenge, but the first to actually turn in a script was Warren Manzi, a playwright then only twenty-six years old. Manzi’s draft, titled Clue and dated March 29, 1982, was 152 pages in length and concerned a writer, his genius-level daughter and his editor tracking a killer who’s using Clue as the basis for their crimes. In a bid to attach a director, Peter Guber sent the script to John Landis, whose latest film An American Werewolf In London (1981) had been produced by PolyGram Pictures. Speaking to Adam B. Vary with BuzzFeed in 2013, Landis would state, “It was a classic murder-mystery with a bunch of characters. I just loved the idea of playing it as farce.” Landis didn’t love the script, mandating that a movie based on Clue make zero reference to the game, its mystery one that anyone could enjoy.

Landis, who’d co-written The Blues Brothers (1980) with Dan Aykroyd based on the actor’s original script and authored An American Werewolf In London, sketched a treatment for Clue. He wanted the story to take place in real time, 90 minutes of story told in 90 minutes. It would be set in the 1950s, a time period Landis felt had been overlooked and offered colorful costuming. And it would take place in Palm Beach, Florida, where the six characters, each victims of blackmail, are summoned to the mansion of their tormentor, Mr. Boddy. Also present is a butler, who Landis penciled in for John Cleese and referred to as “Cleese,” as well as a French maid and a cook. The butler, who is also a victim of Boddy’s blackmail, equips each of the guests with a weapon, and when a tropical storm knocks the electricity out, someone murders Boddy in the dark. Trapped by the storm, the characters must find not only the who, but also the how, of the killer in their midst. Realizing he’d concocted a crime with no solution, much less four of them, by October 1982, Landis had settled on playwright/ screenwriter Tom Stoppard to write a screenplay. In January 1983, Stoppard officially boarded Clue, with Debra Hill producing and Landis attached to direct for Universal Pictures.

Stoppard got as far as half of a draft of Clue, but by March 1983, had encountered enough resistance to write Landis a letter in which he not only withdrew from the project but included a check reimbursing him for the fee he’d accepted. (Contacted by Vary for the BuzzFeed article, the 76-year-old Stoppard had no recollection of Clue). Landis next contacted Stephen Sondheim & Anthony Perkins, the lyricist and actor having authored the screenplay for The Last of Sheila (1973), an American whodunit inspired by scavenger hunts the men had put together for their show business friends. Landis took several delightful lunches with the duo, who Universal either weren’t familiar with, or whose fees were considered exorbitant, or both. Not ready to give up, Landis recalled a BBC sitcom he’d seen while working in England called Yes, Minister. The original series, which aired over 22 episodes from 1980-1984, was written by Antony Jay and Jonathan Lynn. Studying law at Pembroke College in Cambridge–the same as John Cleese had–Lynn also got into performing arts, awarded a spot on the Cambridge Circus. Rather than barristing, he went into acting, cited as Most Promising Actor in 1965 for his West End debut in Green Julia. Lynn began to supplement his acting with writing gigs, for sketch comedy and television, ultimately taking over scripting duties with George Layton for the sitcom On the Buses. Having lost the acting spark, Lynn was being paid well enough as a writer to build a résumé as a director of British theater, where he was in high demand when his agent told him that an American producer named Peter Guber was in London and wanted to meet with him.

Guber told Lynn he had the perfect writing project for him. Lynn knew Clue, having played it as a boy, and as a father with his own son. Speaking to John Stanley of the San Francisco Chronicle in December 1985, Lynn mused, “It’s basically an intellectual process of elimination, which requires skill as well as luck. It’s a question of deducing three points of information: Who did it, where was it done, and how was it done. But when they told me they wanted to make a film version of the game, I thought they were daft. It was an absurd idea. Yet they insisted they were serious. And they insisted enough to convince me. And that’s how it started.” Encouraged by his agent to humor the Americans, Lynn was flown to Los Angeles to meet with Debra Hill and John Landis. The director performed his story for Lynn, acting out each part and jumping on his desk at one point. Enthralled, Lynn asked him who the murderer was. Landis had no idea, needing a writer to sort that out. Dubious he could, Lynn gave Landis a few notes the next day, which were good enough to land him the job of writing Clue.

Lynn returned to England and in December 1983 began writing. Fortuitously, the period of American history he was most familiar with was the 1950s, namely the Red Scare. Much of Lynn’s knowledge came from friendships with Americans like Donald Ogden Stewart, screenwriter of The Philadelphia Story (1940) and suspected Communist who’d refused to name names to the House of Un-American Activities, and blacklisted from work in the States, emigrated to London with his wife. Lynn set his script in New England of 1954, his first draft touching on the paranoia of the Joe McCarthy hearings. Lynn approached Clue as a comedy, but not a parody, and unlike Neil Simon’s efforts for the whodunit Murder By Death (1976), wanted to craft a credible mystery underneath the comic bits. He determined that Col. Mustard, Miss Scarlet, Mrs. White, Mr. Green, Prof. Plum and Mrs. Peacock would be pseudonyms assigned to keep their blackmailed identities secret by the butler, who Lynn renamed Wadsworth. He’d been working on the play Joe Orton’s Loot and pictured leading man Leonard Rossiter an ideal butler for a farce.

Dated May 4, 1984, Lynn’s first draft of Clue ran 200 pages, its excessive length due to the amount of dialogue needed for Wadsworth to explain not one, two, or three, but four endings. Incorporating notes from Landis, Lynn completed a second draft in June. The lengthy development of Clue had at least two effects on its production. A new regime at Universal had no interest in spending money on a project the outgoing regime had nurtured, at least not Clue. Paramount Pictures, where John Landis had directed a blockbuster in Trading Places (1983), reimbursed Universal its development costs to keep the director on their lot. Then shortly after Lynn turned in his script, Landis made the decision to direct the lavish action/ comedy Spies Like Us (1985) for Warner Bros., from an original screenplay by Dan Aykroyd & Dave Thomas. Unavailable for at least a year, Landis sold Paramount’s president of production Dawn Steel on Jonathan Lynn being capable of stepping in to direct Clue, his script dialed in (the WGA would award screenplay credit to Lynn, story to Lynn and John Landis), and most of it ready to be shot in a controlled environment on the studio backlot at a modest budget. Landis and his producing partner George Folsey Jr. retained executive producer credits, as did Peter Guber and Jon Peters.

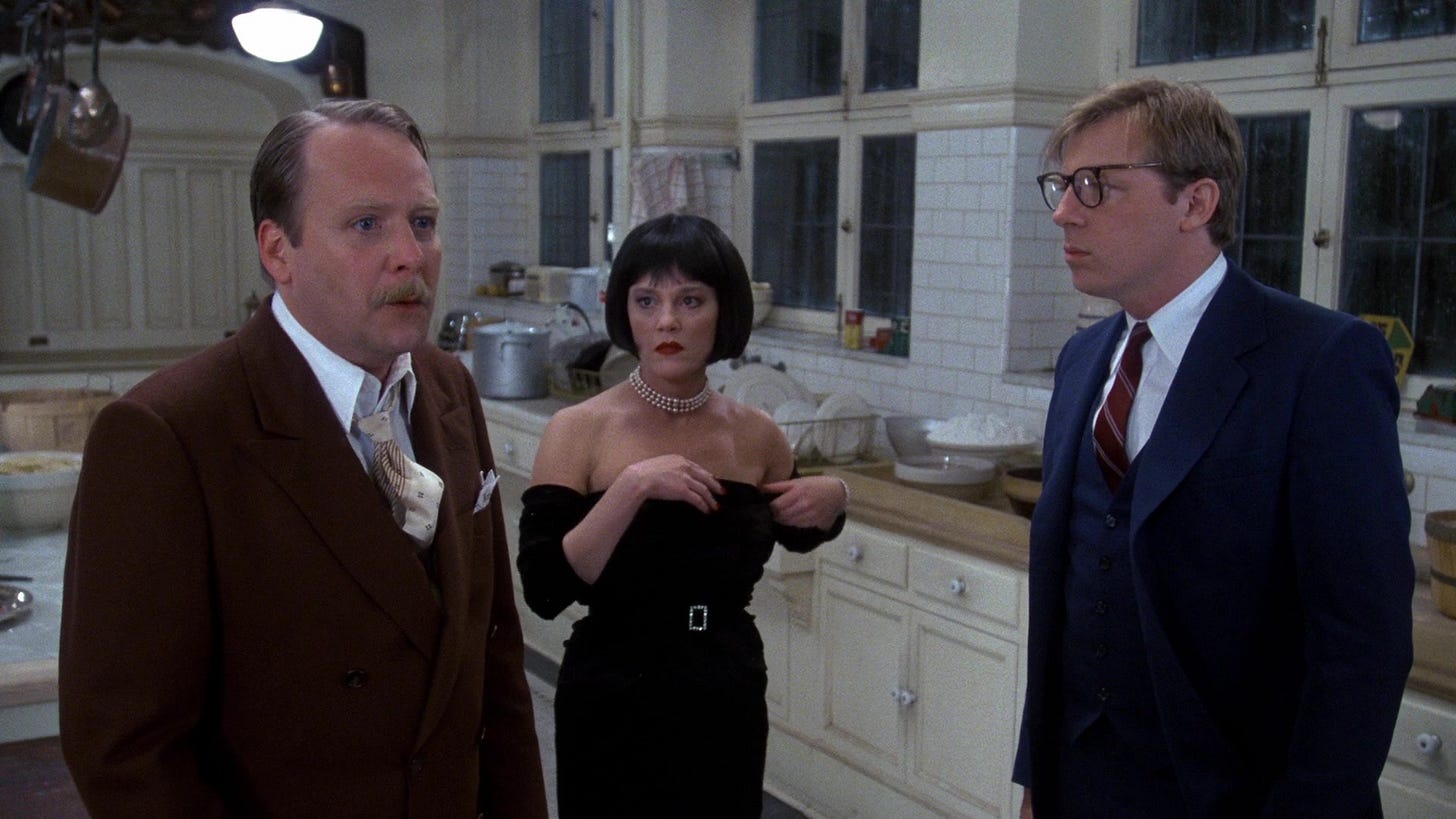

While Jonathan Lynn did not have a final say on casting, he did have input. Madeline Kahn surprised Lynn by asking to play perhaps the most underwritten part in Clue, Mrs. White. With Kahn in mind, Lynn revised his script to give her more to do. Otherwise, none of the characters were written for specific actors. Leonard Rossiter was no longer in the realm of possibility to play Wadsworth, having collapsed fatally on stage in October 1984. Lynn’s next choice was Rowan Atkinson, star of the British period sitcom Blackadder, but despite assembling an audition reel of the performer’s standup comedy and TV work, Lynn doubted Paramount even considered him. Tim Curry was familiar to the studio, having appeared as a slimy villain in the musical Annie (1982) and soon to be seen (under heavy makeup) in another big film, playing Darkness in Legend (1985). Ironically, Lynn and Curry had attended prep school together in Bath, meeting when Lynn was fourteen and Curry was twelve. To cast the other roles, Lynn took a crash course in American television and movies. Martin Mull and Eileen Brennan had appeared as guests and Christopher Lloyd as a series regular on the sitcom Taxi, and were cast as Colonel Mustard, Mrs. Peacock, and Professor Plum. Michael McKean had introduced the character of Lenny Kosnowski on an episode of Happy Days, which led to him being booked as the character for 149 episodes of the spinoff Laverne & Shirley. McKean was cast as Mr. Green.

Carrie Fisher, who John Landis had worked with on The Blues Brothers, was cast as Miss Scarlet. Jennifer Jason Leigh was the consensus to play Yvette, the French maid, but when she demurred, her manager suggested Colleen Camp. Lynn had written Mr. Boddy as a man who’d believably own a mansion, but someone at Paramount suggested Lee Ving, of the punk band Fear, who’d played hoodlums in Flashdance (1983) and Streets of Fire (1984). With a production budget of $8 million, Clue was set to begin filming at Paramount Studios in May 1985. The driveway, entry door and foyer would be shot on Stage 18, where the massive apartment courtyard for Rear Window (1954) had been constructed, while the other rooms of the mansion were shot on two other stages. Rather than build a ballroom, that scene was picked up over two days at the Busch House in nearby Pasadena. A week before rehearsals were set to begin, Carrie Fisher reported to Lynn that she was admitting herself to a drug rehabilitation facility, but would schedule her treatment around her working hours. As Lynn would later recall, neither Debra Hill or Dawn Steel seemed to consider cocaine addiction an issue, until the insurance company refused to underwrite the movie with Fisher. A call was put in to Lesley Ann Warren, recently nominated for an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in the farce Victor/ Victoria (1982), who was vacationing with family in Greece. Warren had been married to Jon Peters in the late sixties and early seventies, and on very little notice, cut her holiday short and returned to Los Angeles to take over the role of Miss Scarlet.

On the first day of rehearsals for Clue, Jonathan Lynn screened the screwball noir His Girl Friday (1940) directed by Howard Hawks to demonstrate to the cast the pace he was gunning for. Commenting to Stephen Farber of New York Times for an article published August 25, 1985, Lynn would state, “I have a deadly serious commitment to farce, which is very close to tragedy. Both, after all, deal with people at the end of their tether, on the border between sanity and insanity.” Neither Lynn or director of photography Victor J. Kemper was working from storyboards, but did plan their shots somewhat in advance based on what the actors were doing. Having booked the primary cast on the same schedule–eight weeks–and in the same location gave production the feeling of a play being performed. The plan was to shoot Clue in continuity, allowing Lynn and the actors greater ease holding the plot together as they reeled off scenes in a chronological order. But the elaborate sets–by John J. Lloyd, production designer of The Blues Brothers and The Thing (1982)--took more time for Kemper to light than had been anticipated, while Lynn, a first-time film director, had seven to eight actors requiring coverage for any given set-up. As a result, production fell behind, and after roughly four weeks, the schedule was tweaked to complete all the scenes on a particular set, Lynn forced to rely on an encyclopedic knowledge of his script to keep the action straight.

Jonathan Lynn has maintained he was dubious of the gimmick to exhibit Clue with one of four different endings attached. He’d shot all four as written, including one of which came off so muddled that it would be cut entirely, and years later, no two people could agree on what it had been (according to Tim Curry, the fourth ending involved Wadsworth revealing himself to be the murderer, having poisoned the champagne of each guest, contrivances piling up in their frantic hunt for an antidote). In retrospect, Lynn stated his preference was to ship prints with all three endings, but trusted that his producers and the studio knew what they were doing. Their plan was to attach a letter (A, B, C) to each public screening of Clue, advertising them as such in newspapers and at theater box offices, with moviegoers needing to remember which letter they’d seen so they could visit a theater playing a different ending. Paramount screened Clue for the press with all three endings, which only reinforced that moviegoers needed to see all three for them to recommend the picture. According to Roger Ebert, a studio representative was unable or unwilling to confirm whether the order in which the endings had been screened for critics followed the same A-B-C format moviegoers would be presented with.

Virtually every film critic who filed a review of Clue hammered on how confusing the multi-ending gimmick was. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert turned two thumbs down. Writing in the Chicago Tribune, Siskel stated, “When all of these characters are being introduced, Clue is very funny. Each has been given a cute secret and a couple of snappy retorts. But after they are all in the same room together, and the lights go out, so does the film’s inspiration. A murder has been attempted, and the rest of the movie turns the cast into a bunch of mice running on a treadmill.” Siskel gave it 2 ½ stars out of 4. Writing in the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert was not quite as complimentary. “Since none of these events have the slightest significance, the filmmakers have attempted to make Clue into a screwball comedy, with lots of throwaway gags and one-liners. Some of these moments of comedy are funny. Most are not. The cast looks promising … but the screenplay is so very very thin that they spend most of their time looking frustrated, as if they’d just been cut off right before they were about to say something interesting.” Ebert gave it 2 stars out of 4. On At the Movies, Siskel & Ebert agreed that Ending A was by far the best of the three, and the nation’s most familiar film critics urged moviegoers to avoid theaters exhibiting B or C.

Clue opened December 13, 1985 in 1,006 theaters in the U.S. It went head-to-head against The Jewel of the Nile, a mediocre sequel to Romancing the Stone (1984) that sold three times as many tickets as Clue did in its opening weekend, while Rocky IV and Spies Like Us continued to dominate the box office. Paramount expanded Clue marginally in its second weekend, to 1,022 theaters, but realized that moviegoers were not only not showing up in large numbers, but those who did weren’t coming back. As Out of Africa and The Color Purple opened in limited release, and Walt Disney Pictures re-issued One Hundred and One Dalmatians (1961) for Christmas, Clue sank, spending one weekend among the top ten grossing films in the U.S. Future prints–on VHS, laserdisc, DVD, basic and pay cable, streaming–included all three endings, “How It Might Have Happened” (A), “How About This?” (B), and “Here’s What Really Happened” (C) separated by title cards, and it was on television where Clue grew in popularity.

The first hint John Landis had that Clue may have found its audience was when an eighth grade theater arts program “somewhere in the Midwest” wrote to him for permission to stage a live performance at their school. Landis advised the students not to tell Paramount; as long as they didn’t charge admission, they could stage whatever they wanted. The thirteen-year-olds did, and sent Landis back a videotape of their show. A stage musical (Clue the Musical) previewed in Baltimore in 1995 and reached Off-Broadway in December 1997, where it closed after twenty-nine performances. Far more popular was a stage adaptation of Jonathan Lynn’s screenplay by Sandy Rustin. Clue: On Stage opened in 2017 at the Bucks County Playhouse in New Hope, Pennsylvania, and from humble beginnings, would be performed by regional theater from La Mirada, California to Oxford, Maine, with many high schools getting in on the act (perhaps due to theater arts instructors who were more postmodern in their tastes than Noises Off). Jonathan Lynn, who couldn’t get a job in the States until his CV as a writer/ director landed him directing duties on My Cousin Vinny (1992), told BuzzFeed in 2013 that Clue is the one he gets the most fan mail about. He hasn’t tried to divine why. “I saw Lesley Ann Warren a few months ago, and she said, ‘People love it now, you know.’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ And then when I saw Michael McKean a few months ago, he said, ‘You know, people like it now.’ And I said, ‘Yeah.’ That’s the extent of the conversation. You move on.”

Some of the qualities that make a board game fun are similar to the qualities that make a suitable play fun, and the film adaptation of Clue mines the best of both. Enjoyable from start to finish, the movie does play best in a group, if not a party environment, with audience participation adding to its enjoyment (there’s a bit of “I say Miss Scarlet did it. She knew about the secret passage … “It’s Professor Plum. He had the revolver …”) The filmmakers don’t try to coast on nostalgia, or the novelty of depicting characters from our childhoods in live action. Instead, they throw an intriguing puzzle at the viewer and challenge us to deduce whodunit among several colorful characters, portrayed by pros at situation comedy (the mid-eighties offered a bounty of actors from television that didn’t even stay on the air, like Fernwood 2 Night, which starred Martin Mull, with Fred Willard, Dabney Coleman and Jim Varney appearing early in their careers). While the board game is recommended for players 8 and up, the movie (rated PG by the MPAA “for mild violence, mild sexual innuendo”) tracks older, ages 12 and up. Rather than dumbing the material down, screenwriter Jonathan Lynn, accustomed to writing for British television, trusts that viewers are intellectually capable of keeping up.

Clue wasn’t so much as nominated for an award of any measure, and if the Oscars for 1985 were announced in 1996, could have been rewarded in three major categories: Tim Curry winner for Best Supporting Actor (over Don Ameche, who took career achievement honors for Cocoon), Jonathan Lynn winner for Best Adapted Screenplay (instead of Kurt Luedtke for Out of Africa, the life of Isak Dinesen not nearly as knotted as a mystery with four endings) and Debra Hill nominee for Best Picture (in a year when there was more political calculus than artistic merit for Out of Africa out-polling The Color Purple). Curry claimed he was treated for high blood pressure during production, but what’s remarkable is that the man didn’t suffer a heart attack. Wadsworth is the engine for the entire farce, responsible for keeping the plates spinning, and Curry carries the last half hour of Clue on his shoulders, machine-gunning through pages of dialogue as he sprints from room to room, running through doors and into them. Most of the cast scores at least one assist from Curry, Lynn’s script loaded with funny zingers (Col. Mustard asks Wadsworth, “Are you trying to make me look stupid in front of the other guests?” The butler dead pans, “You don’t need any help from me.” Mustard retorts, “That’s right!”) Debra Hill’s gambit on multiple endings paid off because instead of the movie being easily disposable after its killer is revealed, three endings allow us to rewind and see a completely different movie play out three times. Director of photography Victor J. Kemper deserves accolades for shepherding two first-time directors–Tim Burton and Jonathan Lynn–through what turned out to be two classic comedies, Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985) and Clue, in the same calendar year. Lynn’s screenplay is almost too good to mess up, so intricate as a whodunit that video store clerks could get away with stocking it in the “Mystery/ Suspense” section instead of “Comedy.”

Video rental category: Comedy

Special interest: 24-Hour Time Frame

Hey, good morning Joe! Well, here’s another one that I never saw, but now having read your background information and analysis, I am extremely interested in seeing it. What a great cast! The only root cause I can think of for my absolute blank spot in my music and movie exposure in the 80s, is that I was in school and encapsulated in digesting didactic information and applying it clinically. So I must’ve been in a little exposure cocoon … anyway, as always, great job! thanks for this one. Peace! ✌️CPZ