Cat People (1982)

Reimagining of 1940s horror noir a gumbo of spells and spills

In the month of October, Video Days is looking out for scaredy cats, counting down to All Hallows’ Eve with seven horror movies in ascending scariness.

CAT PEOPLE (1982) is visible in a very narrow band that requires greater effort to access or appreciate than it could. Less dark fantasy and more urban faerie tale, its characters struggle against roles predetermined by myth. Rather than begin in the ordinary world or ground itself in the familiar, the filmmaking is hyperstylized and offers very little of substance to relate to. Yet led by terrific performances intertwined with noirish doom, this all-eighties, all-practical synthesis of lighting, music and sexual tension never bores.

Val Lewton was born Vladimir Hofschneider and immigrated to the U.S. from Russia at the age of 5, with his mother and sister, in 1909. His mother Nina had left his father, and in doing so, took back her maiden name: Leventon. Nina’s sister Alla Nazimova was a successful actor of stage and (silent) screen in the 1910s and ‘20s, and after spending some of his youth at her estate in Rye, New York, Lewton grew up in neighboring Port Chester. By 16, he was working as a reporter for the Darier-Stamford Review, where according to legend, Lewton was fired for fabricating a sensational story about kosher chickens perishing in a heatwave. Lewton graduated from Columbia University with a degree in legitimate journalism and started cranking out fiction. His pulp novel No Bed Of Her Own was published in 1932 and served as the basis for a Clark Gable-Carole Lombard picture released that year under the title No Man Of Her Own. By 1928, Nina Leventon had been promoted to head of the story department at MGM, and with the Great Depression putting a dent on how much her son could earn as a novelist, she got him a job as a story editor for producer David O. Selznick in Los Angeles.

Lewton would later joke that his punishment for falling asleep during dailies for Gone With the Wind (1939) was being promoted by Selznick to producer. He was put in charge of ordering a script for Selznick’s adaptation of Jane Eyre (1943). Lewton went to see a play about the Brontë sisters titled Embers at Haworth by DeWitt Bodeen and employed the playwright as a research assistant. The wittiest Hollywood anecdote about Lewton held that while at a party, the executive vice-president of production for RKO Pictures, Charles Koerner, spotted him and asked the hostess who he was. She responded that Lewton wrote horrible novels, but Koerner supposedly heard “horror novels” and set up a meeting with the writer/ producer. What is true was that RKO was in financial distress. Its partnership with wunderkind director Orson Welles would come at a considerable expense, Citizen Kane (1941) and The Magnificent Ambersons (1942) headed to quiet theaters long before the former was polled by critics and scholars as the best picture ever made. To turn their fortunes around, RKO sought to emulate Universal Pictures, another thrifty outfit, which had produced a series of inexpensive but very popular monster movies: Dracula (1931), Frankenstein (1931), The Mummy (1932), Bride of Frankenstein (1935), The Wolf Man (1941), with several sequels apiece.

In 1941, on a salary of $150/ week, Val Lewton was placed in charge of RKO’s new horror unit. His pictures were capped at production budgets of $150,000, their running times at roughly 75 minutes to maximize screenings per day, and RKO would provide Lewton the titles to assemble a movie around. Otherwise, he had autonomy–less than Welles in the grand scheme of things, but creative freedom–to do whatever else he wanted. The writer/ producer put DeWitt Bodeen on the payroll (at $75/ week). Lobbed the title Cat People, Lewton and Bodeen inverted the plot of The Wolf Man, drawing up a story about a virginal fashion illustrator named Irena Dubrovna, whose relationship with an engineer at the Central Park Zoo is complicated by her belief that if sexually aroused, she will transform into a black leopard and destroy her lover. To play the tragic heroine, Lewton cast Simone Simon, a French actor who’d made her film debut in 1931, reached Hollywood under contract to Twentieth Century Fox in 1936 and after returning to France to work with a master director (Jean Renoir) on a prestige film (Le Bete Humaine, 1938), was back in L.A. for the money, playing vixens from hell in her two most popular films, All That Money Can Buy (1942) and Cat People.

Kent Smith was cast as her paramour Oliver Reed and Jane Randolph as her competition, Oliver’s assistant Alice Moore. On a production budget of $134,000, Cat People commenced filming in July 1942, on the RKO lot on Gower Street. Jacques Tourneur, born in Paris and working in the American film business since the age of 10, directed a screenplay credited to DeWitt Bodeen. Despite the lanes their producer had stuck to, RKO was anxious about the picture, which under Lewton’s supervision, traded on psychological horror rather than men transforming into monsters and rampaging through the countryside. What the viewer imagined they saw was scarier than anything Lewton showed. Four months after Tourneur began shooting, Cat People premiered in New York and was distributed nationwide on Christmas Day 1942. It was monstrously successful, grossing as much as $4 million in its domestic run (also released that year, Walt Disney’s Bambi earned $3 million in its initial release, while Yankee Doodle Dandy starring James Cagney was considered a blockbuster with $6 million in ticket sales). Val Lewton would produce eleven horror films for RKO, reteaming with Tourneur for I Walked With A Zombie (1943). Editor Robert Wise, who’d cut Citizen Kane and The Magnificent Ambersons, was promoted to director for The Curse of the Cat People (1944) and The Body Snatcher (1945).

In 1974, producer Charles Fries optioned the remake rights to Cat People from RKO. His ambition was for a low budget exploitation picture simpatico with the original. Fries commissioned a script from Bob Clark, the Canadian director who’d made the first of the neo-slasher films in Black Christmas (1974). The psychological horror of Cat People was out of vogue the moment The Texas Chainsaw Massacre (1974) began tearing through towns, and by 1978, financing had eluded Fries when he was unable to book Raquel Welch in the lead role. Fries sold Universal Pictures president Ned Tanen on a remake of Cat People at a time when the studio was active in horror, developing a remake of The Thing From Another World (1951) as a possible assignment for director Tobe Hooper, who’d direct The Funhouse (1981) for Universal instead. Commissioning a new script, the studio hired Alan Ormsby, Bob Clark’s writing collaborator on the horror/ comedy Children Don’t Play With Dead Things (1972). Ormsby had also written the thriller Dead of Night (1974) for Clark, and was on the ascent, authoring My Bodyguard (1980), a crowd-pleasing sleeper hit in the U.S.

On the strength of Ormsby’s script, Universal offered the job of directing Cat People to Paul Schrader, author of Taxi Driver (1976) who’d written and directed one provocative film after another (after another): Blue Collar (1978), Hardcore (1979), American Gigolo (1980). The latter had performed reasonably well commercially, crashing through sexual taboos, but stylishly, with Richard Gere in the title role. Universal retained the services of the film’s producer, Jerry Bruckheimer, to come aboard Cat People as executive producer. Schrader had yet to direct a film he didn’t write, but after typing non-stop for a decade–he’d also crafted the scripts from which The Yakuza (1975) and Rolling Thunder (1977) were based–Schrader’s creative well was dry. He was open to directing a genre picture for hire, one that transitioned out of street-level realism to fantasy and heightened reality. Appropriate for a film that would be urban, noir and sexually charged, Schrader and Bruckheimer employed their collaborators from American Gigolo. Art director and set designer Ferdinando Scarfiotti, who at the dawn of MTV had taken his talents to Hollywood as a “visual consultant,” was rehired to advise Schrader on the look and feel of Cat People. American Gigolo director of photography John Bailey, art director Edward Richardson and composer Giorgio Moroder were also retained.

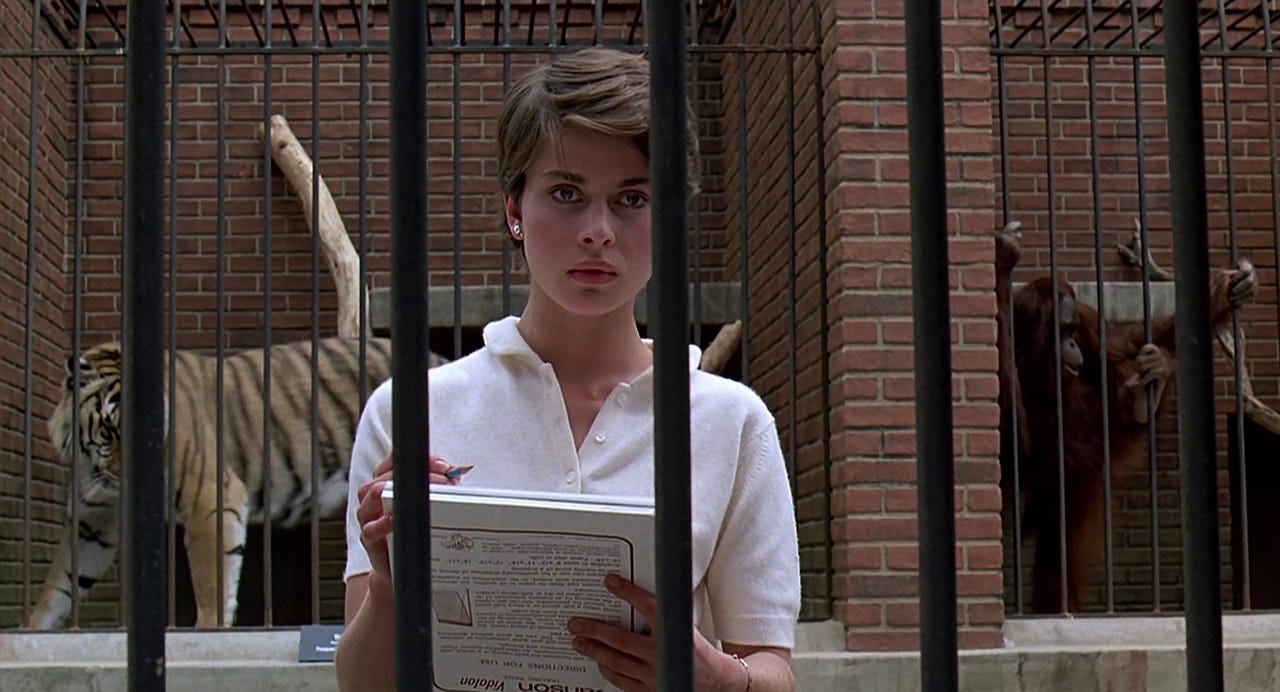

To play their doomed heroine Irena Gallier, the filmmakers had a hard target. The screenplay (credited to Alan Ormsby, from a story by DeWitt Bodeen) hinged on Irena being a virgin, so the actor playing her needed to be a young adult, with an unspecified nationality, and beauty. Alone in the top tier was Nastassja Kinski, the German actor who’d made an international splash as the title character in Tess, Roman Polanski’s adaptation of Tess of the d’Urbervilles, released in Europe in late 1979 and the U.S. a year later. Kinski had booked a leading role in Francis Coppola’s musical One From the Heart (1982) and a day after completing work in Los Angeles, would fly to New Orleans to star in Cat People. To play her paramour, a zoologist with the Audubon Zoological Garden, John Heard was cast. Heard had starred in Between the Lines (1977) and Chilly Scenes of Winter (1979) for writer/ director Joan Micklin Silver and played the irascible title character in the film noir Cutter’s Way (1981) opposite Jeff Bridges. Unlike Bridges, Heard had less to lose from a sexually provocative and graphically violent horror movie. Annette O’Toole, who’d played Tammy Wynette in a TV movie based on the country singer’s life, was cast as Alice Perrin, Oliver’s assistant.

Second-billed to Kinski was Malcolm McDowell as Irena’s estranged brother Paul, a church leader of ambiguous nationality in the Crescent City. Ruby Dee, who hadn’t appeared in a movie since Cool Red (1976) for her husband, actor/ director Ossie Davis, accepted the role of Female (pronounced like Tamale), a Creole housekeeper. Ed Begley Jr., Frankie Faison and John Larroquette also joined the cast. On a budget of $12 million (which the Los Angeles Times would later push to $13.5 million) shooting commenced April 1981 in New Orleans. After one month of location work, production returned to the Universal Studios lot in Los Angeles, where interiors and scenes involving caged animals, mostly the large cats, were filmed over another month. Schrader learned that black leopards are nocturnal and impossible to train, and would not hit a mark (asked how he’d know something was going wrong with the leopards, animal trainer Mark Dumas told Schrader he’d see him running). For scenes involving the cat outside of its cage, a mountain lion, a much tamer animal, was dyed black.

The task of taming a theme song fell on Giorgio Moroder, the synth/ electronica pioneer who’d co-written and produced hits for Donna Summer at the peak of disco and won an Academy Award composing the score for Midnight Express (1978). With American Gigolo, Moroder had recorded an instrumental track, and after Stevie Nicks passed on the job, commissioned the lyrics and performance of a theme to Blondie. Their contribution–“Call Me”--became one of the band’s signature hits. For Cat People, Moroder called David Bowie. The pop icon summoned Moroder to Mountain Studios in the Swiss Alps to record the song Bowie had written and would perform: “Cat People (Putting Out Fire).” The track would be heard by far more moviegoers in Inglorious Basterds (2009) for the sequence in which Shosanna Dreyfus (Mélanie Laurent) puts her night of vengeance against the Nazi regime into motion. Speaking to Rolling Stone, filmmaker Quentin Tarantino said this about “Cat People”: “It’s one of my favorite David Bowie songs of the eighties, but I never liked the way he used it, because Paul Schrader didn’t really use it in the movie. He just threw it in the closing credits and I remember me and all the other guys at Video Archives were very disappointed by that. We’d go, ‘Man, if we had a song like that written for our movie, we’d build a 20-minute sequence around it! So I did.”

Quentin Tarantino’s “Cat People” sequence in Inglorious Basterds runs just under 4 minutes, but the director might’ve slammed the door on Schrader hard if Nastassja Kinski had accepted the role of German film star and double agent Bridget von Hammersmark. She was offered the part and declined. Commenting on the Without Your Head podcast for the 40th anniversary of Cat People, Schrader maintained that he didn’t feel Bowie’s ultramodern dance track was appropriate for the prehistoric scenes which initiate the film, but admitted if he had placed it up front, the song might’ve been a hit. Cat People was not put through a sophisticated test screening process and according to Schrader, the first indication he might have a problem came after the movie was in theaters: “I remember quite vividly–we didn’t do much previewing back then–Jerry Bruckheimer was the producer, and Jerry and I went to an opening night at the Avco in Westwood, in Los Angeles. And we were sitting way in the back. In front of us were a couple of young girls, I would say maybe seventeen or so. And it came to the ending, when he starts tying her to the bed and I do those sort of fetishistic closeups. And the one girl turned to the other and just went, ‘Oh my God.’ I leaned into Jerry and said, “I think we went a little too far.’”

Cat People opened April 2, 1982 on 600 screens in the U.S. Reviews from leading critics were ecstatic. In the final months they were on public television, Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert gave Cat People two thumbs up. Siskel credited Schrader for continuing the trend of Hardcore and American Gigolo “walking us through a lot of sexual taboos” and compared some of its suspense to Alfred Hitchcock. Ebert admired the picture for its mingling of magic with the everyday, and having only seen Nastassja Kinski (billed as “Nastassia Kinski”) in two other films, compared her impact to Marilyn Monroe. Siskel agreed. “She is compelling. As soon as the camera comes on in this movie, you’re watching. Unpredictable, a strange look, an androgynous look perhaps. I think she is perfect casting here, both her and Malcolm McDowell.” Writing in the New York Times, even Vincent Canby struck a complimentary tone: “When the chips are down, Mr. Schrader deals in the kind of explicit shock effects that might have prompted Mr. Lewton to throw up his hands in despair. Yet, if you like horror films, the new Cat People is a good deal of fun–beautiful, baroque, erotic and blunt.” Its appeal was lost on teenagers, who were flocking to a raunchy comedy directed–of all people–by Bob Clark titled Porky’s (1981) that went into wide release in March 1982 and held onto #1 at the U.S. box office for eight consecutive weekends. A Richard Pryor movie not meant to be funny–Some Kind of Hero (1982)--was near the top of the charts with one that was, Richard Pryor: Live on the Sunset Strip (1982). Cat People was ignored, spending three weekends at the bottom of the top ten.

Cat People gets off to a fantastic start with moments in what appears to be the Middle East of antiquity. Shot on the Universal Studios backlot, the prologue not only looks and sounds breathtaking–a synthesis of Ferdinando Scarfiotti’s eye for design, John Bailey’s evocative lighting, Giorgio Moroder’s score as it teases cues from the David Bowie theme, and most beautifully, matte work by Albert Whitlock, Universal’s visual effects wizard whose backgrounds (all paint, no computer) were seen in The Birds (1963), Earthquake (1970) and The Sting (1973)--but the prologue does something that vampire, werewolf or zombie movies seldom do. The filmmakers address where its monster comes from, at least as far as myth is concerned. The problems with Cat People begin in New Orleans, where Paul Schrader takes over for Scarfiotti in directing the movie. Working with the largest budget and highest commercial expectations of his career, Schrader is tasked with serving too many masters: the 1970s and the 1980s, European film and American movies, monster picture and psychological horror. Scenes like Irena’s airport reunion with her brother, or Frankie Faison’s bits as a police detective, are scattershot, like no one has figured out what movie they’re making. The story unfolds like a Jack the Ripper thriller, with the English-accented Malcolm McDowell character going out at night to victimize prostitutes–maybe as a leopard, maybe as a man dealing with his sexual anxieties by pretending he’s a leopard–while the Nastassja Kinski character grapples with similar hangups.

There’s a really good movie buried in Cat People: a genre thriller with psychosexual intrigue. In his script, Alan Ormsby gives Irena and Paul a circus background, plausibly explaining their fear of intimacy and their kinship with nature’s freaks, as well as a certain acrobatic ability. Unfortunately, the French Quarter creep so compellingly played by McDowell never steps up to menace his sister’s co-workers, and he exits the picture too soon. Kinski and John Heard are also really good, both apart from and in their scenes with each other, bringing an exotic fragility and Big Easy blend of blue and white collar male to their characters. The sexual content leaves much more to the imagination than the graphic violence, signalling a larger crisis in the filmmaking. The first half hour struggles to find a point of view, gazing at Kinski from afar, like a hunter would a game animal. As directed by Schrader, Kinski is neither empowered enough for us to fear, or sympathetic enough for us to care about. Like too much of Cat People, Irena swings between poles, villain and heroine. Schrader objectifies her, and Irena ends up in a place a lot of male directors would put her. The sexual intrigue leaves a lasting mark, along with the performances of the three leads, and credit goes to Mark Dumas and animal supplier/ trainer Steve Martin, the black leopards in the film so ferocious and unpredictable that their scenes, without a computer effect in sight, are scary.

Video rental category: Horror

Special interest: Femme Fatale