Blue Steel

Kathryn Biglelow's hybrid horror/ cop thriller hits differently after hours

Video Days orders readers to surrender their badge and gun and while suspended for the month of May, return to ten films trafficking in law and order.

BLUE STEEL (1990) is a mood-inducing thriller that plays best very late at night or early in the morning, when coffee and a Pop-Tart offers the viewer fuel to stay awake another 102 minutes. Under the glare of daylight, it’s an absurd variation on Dirty Harry (1971) in which Callahan is unavailable and it’s up to his partner, a female like the one he bristled at being teamed with in The Enforcer (1976), to catch the psycho. The fact that she’s dating the psycho almost makes Harry’s objections valid, but taken as a work of high style and nightmarish paranoia, the film excels.

Kathryn Bigelow was born in San Carlos, California in the Bay Area, but grew up in Southern California, in Fullerton, in the 1960s. Her mother was a librarian and her father the manager of a paint factory, his unrealized aspirations to be a cartoonist directing his daughter toward the arts. Bigelow briefly attended San Francisco Art Institute to study painting but by the age of nineteen, headed to New York. Someone there told her the Whitney Museum had a terrific independent study program, which Bigelow would enter in 1972. Among a variety of odd jobs, she ended up as an assistant to video and installation artist Vito Acconci, putting together film loops for his shows. Scrounging a camera and a crew composed of her friends, Bigelow made a short film on her own, catching the filmmaking bug. This led her to apply to grad school at Columbia University, earning a master’s degree in film theory and criticism, and graduating with a short film titled The Set-Up (1978), in which an alley fight between two men is overlaid with scholarly commentary.

With a classmate named Monty Montgomery, Bigelow co-wrote and co-directed a feature, U.S. 17, in which a gang of motorcycle riding greasers wreck havoc in a small town. Though shooting was underway in September 1980, the film wouldn’t be distributed (by Atlantic Releasing Corporation) to general audiences until January 1984, as The Loveless. By then, filmmaker Walter Hill had screened the picture in lieu of casting Bigelow’s lead actor, Willem Dafoe, as the greaser villain in Streets of Fire (1984). Asked what she was working on, Bigelow pitched Hill a movie about gangs in Spanish Harlem. He helped her secure a development deal at Universal Pictures, with Bigelow to write and direct, and Hill to produce. The fate of Streets of Fire, as well as regime change at Universal, resulted in their project being placed in turnaround, but Oliver Stone read the script and reached out to Bigelow to collaborate with him on a script he wanted to write on the gang violence epidemic in South Central Los Angeles. The year was 1985.

Bigelow & Stone’s project was preempted when the money came in for Stone to direct a movie, Salvador (1986), leaving Bigelow jobless again. She was contacted by another fan of her work, a screenwriter in his early twenties named Eric Red. He recognized in Bigelow’s writing a shared fascination with the nature of evil and with violence taking root in Americana. Red had sold his first script, The Hitcher (1986), to TriStar Pictures along those same lines but was almost as far away from being offered an opportunity to direct as Bigelow. They made a pact to write together, the sales of their scripts contingent on one of them being offered directing duties. While their script Undertow wouldn’t be produced with Red behind the camera for another ten years–by Showtime Networks in 1996 with Lou Diamond Phillips, Mia Sara and Charles Dance as the cast–Bigelow fared better with their script Near Dark (1987), for which producers Charles Meeker and Edward S. Feldman raised financing, a vampire picture set on the road with one of the most memorable scenes many who found it had seen in a movie that year.

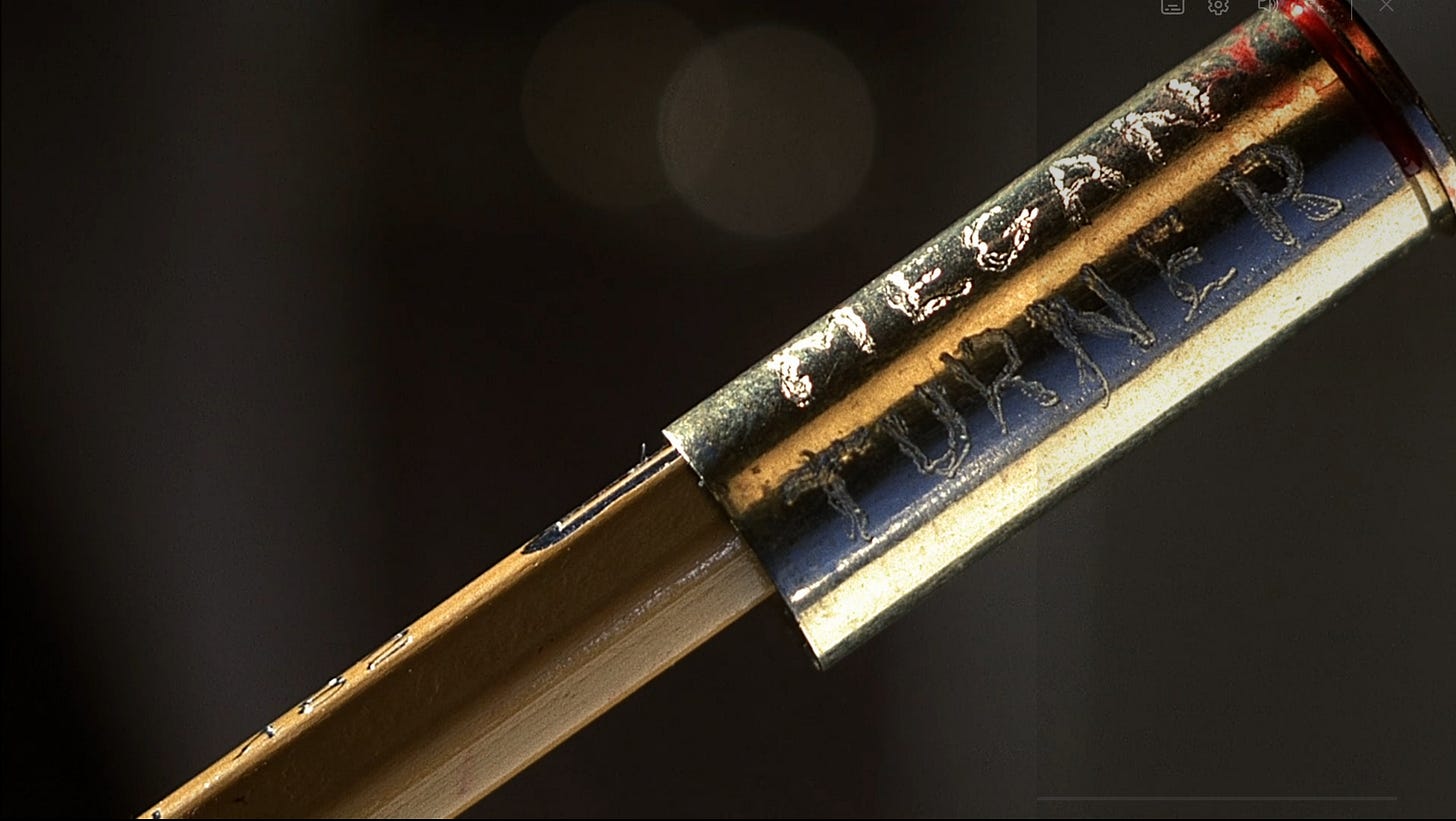

Meanwhile, another Bigelow & Red script had been optioned by Paramount Pictures and placed in turnaround. Titled Blue Steel, it concerned an NYPD officer named Megan Turner who, fresh out of the academy, is involved in a shooting. Her colleagues find it difficult to believe her version of events due to there being no gun recovered at the scene. Shortly thereafter, shell casings with Megan’s name on them start turning up at homicides. Near Dark had garnered Bigelow offers to direct, but projects she deemed soft or lacking in compelling subject matter. What she wanted to do next was Blue Steel. Bigelow reached out to Oliver Stone, who liked the script and passed it to Edward R. Pressman, producer of his films The Hand (1981), Wall Street (1987) and Talk Radio (1988). Blue Steel had been passed over by multiple buyers, the recurring question whether Bigelow was open to rewriting it for a male actor. Bigelow & Red, who’d written Megan Turner with Jamie Lee Curtis as their model, had declined to swap the gender of their protagonist. Pressman was willing to raise financing with a woman in the lead.

With Pressman and Stone as producers, and Bigelow as director, Vestron Pictures rescued Blue Steel from turnaround and set a production budget of $7 million. Jamie Lee Curtis agreed to star and was joined by Ron Silver (whose mix of charm and cunning had impressed Bigelow in the David Mamet play Speed-the-Plow), Clancy Brown, Elizabeth Peña, Kevin Dunn, Richard Jenkins, Philip Bosco and Louise Fletcher. To play the intense stickup man who Megan blows away, Bigelow cast an actor named Tom Sizemore. His gun ends up in the hands of Silver’s character, a commodities trader on Wall Street whose murderous fantasies are unloosed (Pressman, who’d bet on Brian De Palma and Terrence Malick very early in their careers as well as Oliver Stone, would produce the film adaptation of American Psycho, with Mary Harron directing). Shooting commenced in New York in August 1988, while A Fish Called Wanda (1988) featuring Curtis in its ensemble cast was near the top of the box office.

Vestron scheduled Blue Steel for release in October 1989. The company had been launched as a home video distributor and their gamble to go into production had paid off big time in the summer of 1987 with their first film, Dirty Dancing grossing $63 million in the U.S. with at least another $36 million in videocassettes on a budget of $5 million. Since then, nothing had gone right for Vestron. Among sixteen releases in 1988 and eight in 1989, none were measurable commercial successes, whether arthouse fare like Lair of the White Worm (1988) or attempted crowdpleasers like Rebecca DeMornay in And God Created Woman (1988). In June 1989, Vestron folded their theatrical motion picture division and a month later, the company was put up for sale. Among twelve films marooned without a distributor were the Dennis Hopper-directed Backtrack starring Jodie Foster, Communion with Christopher Walken, and the most anticipated, Blue Steel. Bigelow worked on her cut through the fall until MGM/UA stepped in to acquire the picture. It screened at the Sundance Film Festival in January 1990 and opened two months later in 1,307 theaters in the U.S.

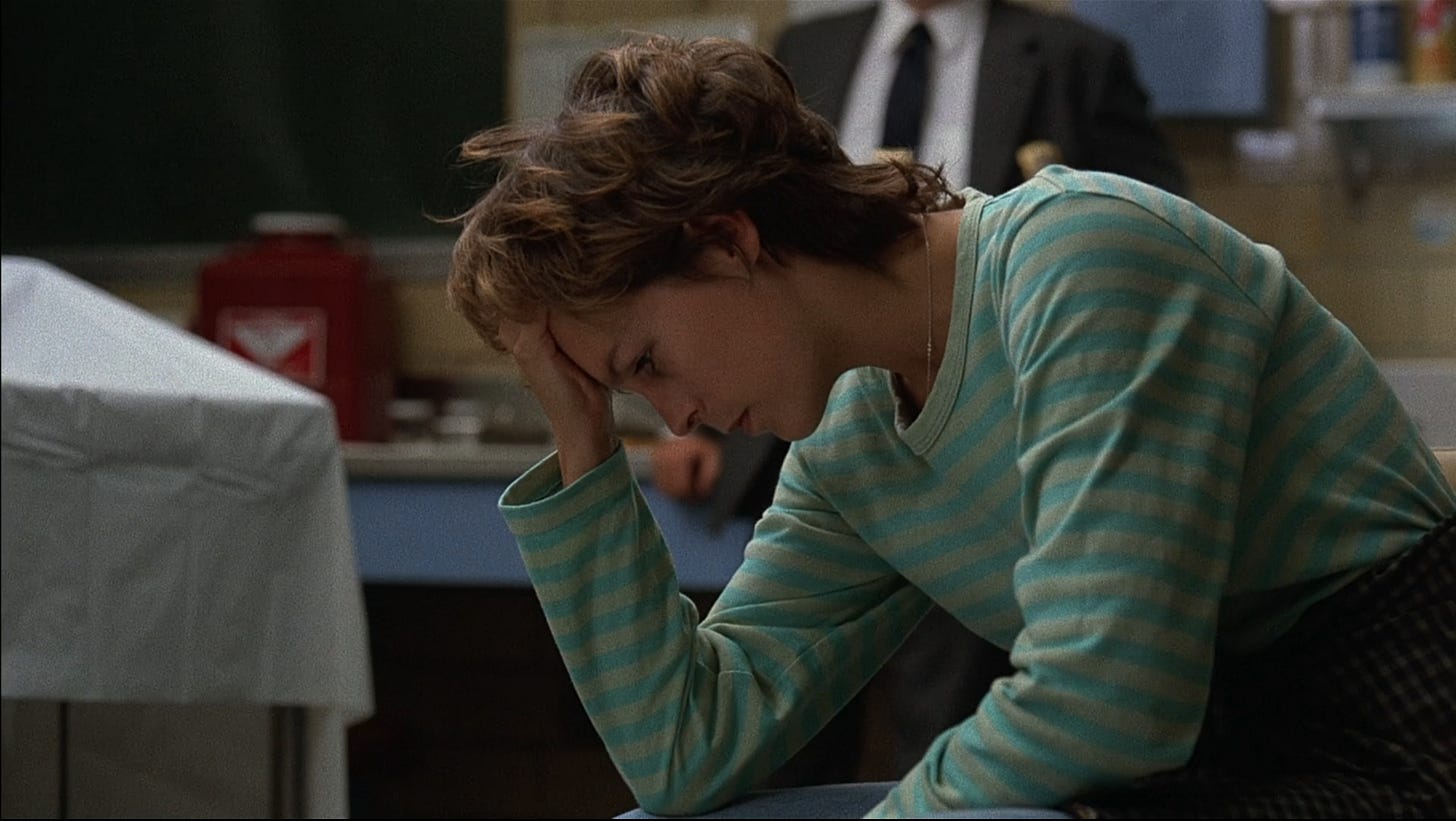

Reviews were a tossup. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert split. Siskel didn’t think anything but the film’s setup–with Curtis playing a rookie cop under pressure–worked. Ebert found her character compelling and the dangers she was put in frightening. Writing for the New York Times, Janet Maslin stated that Bigelow’s “exceptionally fine eye for shape, color and composition gives Blue Steel tremendous style, with a clarity and precision that can be truly breathtaking.” Her suspension of disbelief put to the test, Maslin called it a breakthrough for Bigelow. Opening just after The Hunt For Red October and right before Pretty Woman, with House Party the niche market, word-of-mouth hit the filmmakers might have hoped for, Blue Steel spent two weeks among the top ten grossing films. Most fans of neo-noir embraced it. Karyn Kusama, director of Jennifer’s Body (2009) and the cop thriller Destroyer (2018) starring Nicole Kidman, cited the film’s palpable sense of female paranoia, challenging the assumption that men will be there to protect women. In Kusama’s reading, most of the men in Blue Steel are out to hurt Megan.

On a dry or sober mind, there are things about Blue Steel that stick out as ridiculous. The police shooting that sets the plot in motion defies credulity. Our protagonist is lobbed an armed robbery practically her first hour on the job, which even in the New York of Mayor Ed Koch, must have seemed like hitting the lottery for a woman who just told her partner that she joined the NYPD to shoot people. It’s a facile line we don’t buy, but that Jamie Lee Curtis lacks the relaxed manner to convey as humor. The shooting would’ve been more compelling–particularly with a hard charging actor like Curtis–if her character expressed uncertainty about how she’ll handle herself under fire, having flunked the simulation during training. The logistical inconsistencies begin when rather than wait for her partner, or at least radio dispatch that she’s about to engage an armed robber, she charges in alone. That none of the witnesses, including the cashier, would remember seeing the robber wield a .44 Magnum, is fantasy. None of them would’ve dropped to the ground or feared for their lives unless they saw a gun. It’s just as unlikely that Silver’s character would be able to pocket a hand cannon like that without anyone observing him. And even in the eighties, it’s highly improbable that her superiors would assume Turner fired without provocation, without even considering someone at the scene absconded with the weapon.

Actors were so eager to work with Kathryn Bigelow that the cast was deeper than a Vestron Pictures production had any reason to be. The film has a terrific villain. While it stretches believability that a workaholic would be as potent with the ladies as he is, Ron Silver gives a compelling and very threatening performance as the American psycho. Elizabeth Peña and Matt Craven appear too briefly as Turner’s best friend and prospective suitor, respectively, and Tom Sizemore takes a stock character–the crazed holdup man–and makes him the stuff of nightmares. Director of photography Amir Mokri, who lit Slam Dance (1987) competently but not to suggest this level of artistry, works with Bigelow to give Blue Steel a gorgeously volatile look and feel. Darkness and detail are what set the film apart, even more so than its focus on a policewoman. Giving the filmmakers the benefit of knowing they weren’t interested in logic, Blue Steel plays much better on the small screen at the hour the lunatic fringe are out there awake and much easier to believe might be fixated on us. On that level, Blue Steel is the jewel of the horror trilogy Bigelow began with The Loveless and Near Dark.

Video rental category: Mystery/ Suspense

Special interest: Catch the Psycho

Wow, I barely remember this movie… But after reading all your information, I’ll just go ahead and ask you… Is it worth another look? Jamie Lee Curtis and Ron Silver and especially Tom Sizemore I like a lot … great background information Joe, thanks a lot. Great job! Peace! CPZ.