Big Top Pee-wee

Mismatched milieu dooms tired and unfunny comic fantasy

For the remainder of summer Video Days piles in a vehicle and for those who can’t take a vacation, journeys to unfamiliar places with comedies about strangers in strange lands.

BIG TOP PEE-WEE (1988) takes a wholesome and colorful idea–a new take on the circus film–and blunders from misstep to mistake, virtually nothing beyond its set decoration appealing. It is not funny. It is not exciting, not in terms of its story, characters, or direction. It never reconciles who its audience is: children who discovered Pee-wee Herman on his popular Saturday morning TV show, or hipsters introduced to the character on his 1981 HBO special and appearances on MTV or Late Night with David Letterman. Afforded production perks beyond what Paul Reubens had ever been granted to put on a show, this film treats them like confetti.

Paul Reubens had been cooking ideas for the next Pee-wee Herman movie before Pee-wee’s Big Adventure (1985) opened, its box office returns making the prospects for a sequel definite as opposed to probable. Reubens had grown up in Sarasota, Florida, the so-called “Circus Capital of the World.” Ringling Bros. purchased Barnum & Bailey Circus in 1907 and would consolidate the shows twelve years later, using Sarasota as a winter base for “The Greatest Show on Earth” and establishing the city as their headquarters in 1927. Reubens, who entered theater arts early in his life, was aware of neighbors who worked in the circus, and his high school even offered circus curriculum to train the next generation of performers. In 1985, Reubens started working with John Paragon, a kindred spirit from the Groundlings Theatre who played Jambi in The Pee-wee Herman Show, and Michael Varhol, one of his two co-writers on Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, on the script for a circus-themed Pee-wee adventure.

Reubens & Paragon & Varhol screened every circus movie they could find–the Academy Award winner for Best Picture, The Greatest Show on Earth (1952), and Jumbo (1962) being the best known with Dumbo (1941)–but they struggled to come up with a story. Three months into their efforts to dial in a script, Paragon concluded that the circus milieu was too confining, that Pee-wee needed to bust loose from it, while Varhol advocated for the opposite, enthralled by Pee-wee discovering the circus world this time out. Reubens recycled a few ideas from the draft of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure he’d halfway completed with Phil Hartman & Varhol, in which Pee-wee introduces joy and excitement to the citizenry of a lifeless town. This led Reubens & Varhol to the idea of Pee-wee owning a farm, growing oversized vegetables and hosting a traveling circus troupe when a storm blows them onto his land. Warner Bros. Pictures was allergic to a circus film and to meeting Reubens’ escalated fee to co-write, produce and star in it. The studio passed.

Meanwhile, Michael Chase Walker, the newly appointed Director of Children’s Programming for CBS, launched a campaign to rebuild the network’s appeal among 6-11-year-olds on Saturday mornings. While Reubens wanted to make movies, and his managers Richard Gilbert Abramson and William E. McEuen considered network television to be a step backwards, Walker saw Pee-wee Herman as being exactly who CBS needed to reach a younger audience. Persevering until he was able to pitch Reubens personally, Walker won over the performer, who’d always wanted to do a weekly children’s television show and now had someone offering him the financing and distribution to do so. Reubens & Paragon & Varhol got to work writing the first season of Pee-wee’s Playhouse, with Reubens inviting George McGrath, a member of the Groundlings Theatre who’d serve as head writer on Elvira’s Halloween Special (1986) for MTV, to collaborate with them.

McGrath co-wrote all eighteen episodes of Pee-wee’s Playhouse Season 1 and voiced the puppets Globey, Dog Chair and Cowntess. Debuting September 1986, production on the show would prove contentious enough for Reubens to fire Abramson and McEuen as his managers at the end of the season, as well as dismiss Broadcast Arts, the visual effects house and animation studio that had produced Season 1 and struggled to bring it in on schedule while giving Reubens exactly what he wanted. Not even Paragon was retained to play Jambi in Season 2. Reubens did retain McGrath, who would write four episodes of the sophomore season by himself and co-write the other six with Reubens. Pee-wee’s Playhouse Season 2 was a huge success, #1 in its timeslot and nominated for twelve Daytime Emmy Awards. In July 1987, Paramount Pictures offered Reubens a three-picture deal, $3.5 million to co-write, produce and star in his untitled circus adventure, the studio reserving the right of first refusal on Reubens’ next two films.

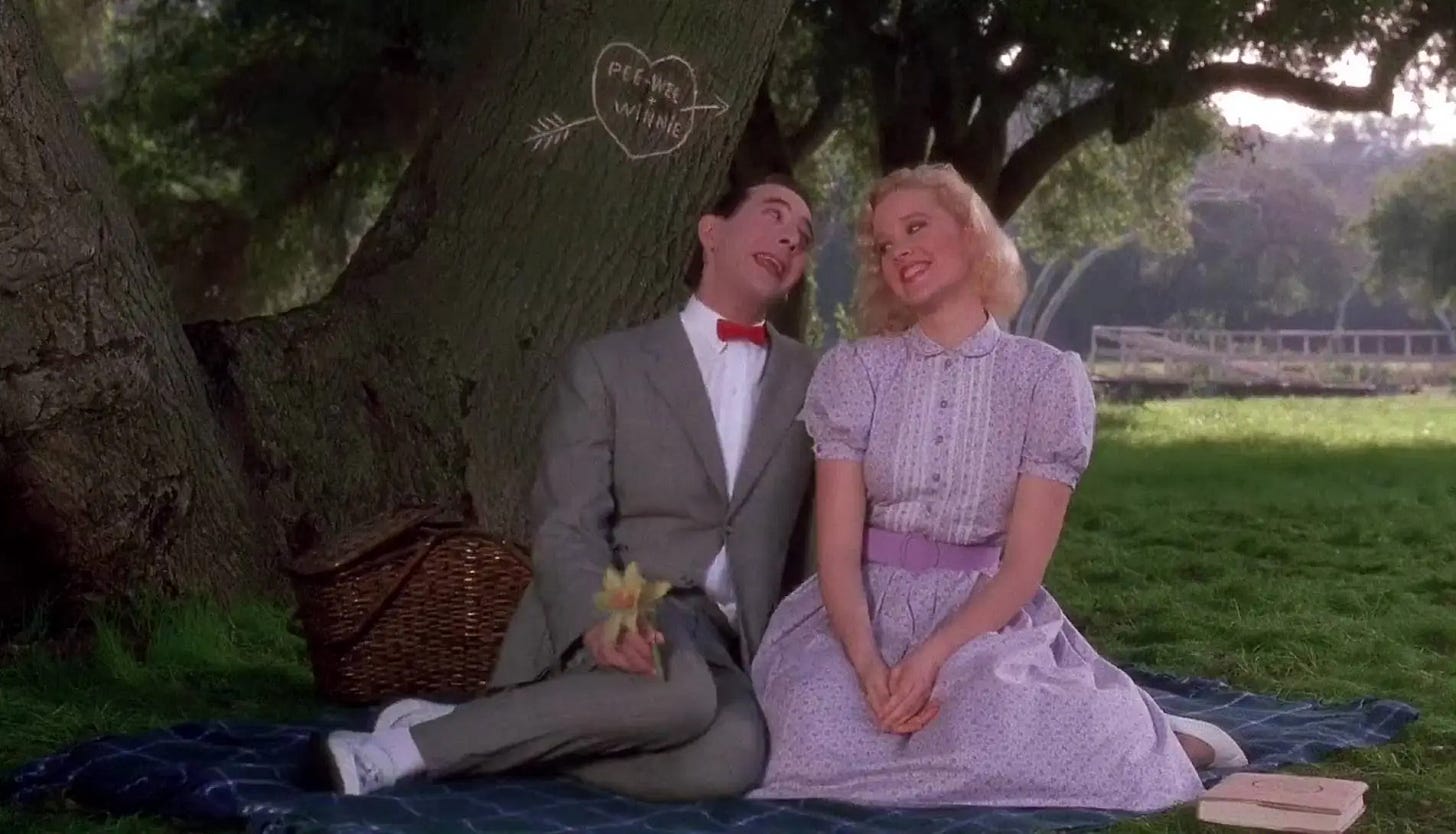

Reubens asked George McGrath to pen the next Pee-wee adventure with him. In what McGrath would later concede sounded like a desire to be the answer to a future trivia question, Reubens wanted Pee-wee to have the longest kiss in motion picture history, the record holder being the lip embrace between Jane Wyman and Regis Toomey in You’re In the Army Now (1941), which lasted 185 seconds (the kissing scene in Big Top Pee-wee between Valeria Golino and Reubens generated so much fidgeting in test screenings it would be chopped down to about a minute and a half, Wyman and Toomey retaining their spot in Guinness World Records). While Pee-wee Herman had previously shown zero interest in girls, a record-breaking kiss necessitated at least one love interest. Reubens & McGrath came up with two, a schoolteacher fiancée named Winnie and a trapeze artist named Gina Piccolapupula. To produce the film with him, Reubens drafted Debra Hill, the prolific young producer of Halloween (1978), Escape From New York (1981), The Dead Zone (1983), Clue (1985) and Adventures In Babysitting (1987). Randal Kleiser, director of Grease (1978) and The Blue Lagoon (1980), had just worked with Reubens on a science fiction adventure for Walt Disney Productions, Flight of the Navigator (1986), which featured Reubens as the voice of the spacecraft’s computer. Kleiser campaigned for and won the job to direct Big Top Pee-wee.

Other than Lynne Marie Stewart — who played Miss Yvonne on Pee-wee’s Playhouse and was cast as Zelda the Bearded Lady — none of the cast members of Pee-wee’s Big Adventure would return, making it less of a redo and more like a restart. Penelope Ann Miller and 22-year-old Valeria Golino (in her film debut by virtue of Reubens insisting the acrobats all be Italian) were cast as Pee-wee’s love interests, Kris Kristofferson as ringmaster Mace Montana and as the voice of Pee-wee’s best friend Vance the Pig, Wayne White, who performed and voiced the characters of Randy and Mr. Kite on Pee-wee’s Playhouse. The only craftspeople from Pee-wee’s Big Adventure returning with Reubens would be Danny Elfman, who agreed to score the picture between working with Tim Burton on Beetlejuice (1988) and Batman (1989). Shooting commenced January 1988 on a publicized budget of $20 million, more than three times what Pee-wee’s Big Adventure ended up costing despite a veteran director juggling far fewer locations. Pee-wee’s farm, the circus and the unnamed town were erected in Golden Oak Ranch, the 890-acre compound outside of Newhall, California owned by Walt Disney Studios and offering meadows, a waterfall and western sets. The concert sequence that opens the film was shot in the auditorium of Hart High School in Santa Clarita.

Big Top Pee-wee opened on July 22, 1988 on 1,256 screens in the U.S. Newspaper critics–many of whom had been on vacation when Pee-wee’s Big Adventure screened in 1985–saw this one and leaned negative. On their syndicated TV show, Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert turned two thumbs down. Siskel criticized the decision to put Pee-wee through a conventional love triangle, the film needing more whimsy, its circus performers dull and townsfolk dull. Ebert thought that Pee-wee belonged in a world of pure fantasy and this new direction lost all the magic of the TV show and previous movie. (Ironically, Big Top Pee-wee offered far more make-believe than Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, but at least to Ebert, didn’t seem like it). Writing in the New York Times, Caryn James cited the effort to make Pee-wee less eccentric. “This new, lukewarm, compromised Pee-wee is remarkably unfunny.” James, like Siskel, wanted more of the movie’s most compelling relationship, that between Pee-wee and Vance the Pig.

The film debuted the same weekend as two other comedies, one of which looked like a hit (Midnight Run) and the other a boondoggle (Caddyshack II). Neither met commercial expectations but were both selling more tickets than Big Top Pee-wee by their second weekend of release, with Who Framed Roger Rabbit?, Coming To America and Die Hard dominating the box office. Pee-wee Herman spent only two weekends among the top ten grossing films in the country and would never appear in a theatrical film again, the Judd Apatow-produced Pee-wee’s Big Holiday (2016) distributed on Netflix. Reubens, who had high hopes for Big Top Pee-wee up to its premiere and the tone of the congratulatory remarks he received immediately after, took its failure hard, having never lost an audience this big before. Richard Abramson–who along with William McEuen was paid an executive producer credit for not working on Big Top Pee-wee–offered that teenagers who Pee-wee Herman had once appealed to stayed away from what the success of Pee-wee’s Playhouse indicated had become the property of kids. McGrath regretted that the failure of Big Top Pee-wee put a stake through Reubens’ plans to introduce Pee-wee into the world of 1950s gangster noir with his next film, which was never made.

There’s a big problem with Big Top Pee-wee and it lies in the film’s wobbly foundation. Whatever the age of the viewer who embraces the character, Pee-wee Herman is a circus. Like a puppet from a children’s television program made both real and knowing, he brings excitement and joy to the adult-like characters he encounters, and our lives as well. By Reubens depositing Pee-wee in the center of a circus, instead of a more mundane environment like a big company, he completely disappears. While his need in Pee-wee’s Big Adventure was to find his stolen bicycle, the character has no need in Big Top Pee-wee, nothing the circus needs to fulfill in him. Meanwhile, the circus troupe has no real use for Pee-wee, their world already filled with travel and wonder. Like a blind date going awkwardly, the only chemistry between the characters is bad chemistry. Pee-wee doesn’t seem remotely curious about anyone but his talking pig, and while Penelope Ann Miller gives the most spirited performance, none of the cast members are amused by Pee-wee this time around. In their defense, there’s nothing especially amusing about a geek being twirled around on a rope or fired out of a cannon. The circus material is flat and pitched mainly at children, while Reubens’ insistence on giving Pee-wee a sex drive seems like a concession to teenagers. Instead of offering something for everyone, Big Top Pee-wee instead gives everyone something to tire of quickly or groan through.

For the script by Paul Reubens & George McGrath to begin to work, the circus needed Pee-wee to help them recapture the magic in their lives, perhaps after he shares a big announcement with Dottie (Elizabeth Daily from Pee-wee’s Big Adventure, whose absence is felt hard) that instead of an engagement ring, he’s using his Hollywood money to purchase the Cabrini Circus and go on the road with his investment. Whether the show is on its last legs because of dwindling box office and this has made its cast members despondent, or the diminishment of their world has soured their lives and led to declining ticket sales, it would’ve given Pee-wee something to fix and something for its broader cast to work with. In addition to casting Benecio Del Toro as “Duke the Dog-Faced Boy” early in his career, Susan Tyrrell is a nice addition as a three-inch tall lady. Both characters should face difficulties–falling in love with a feline-faced girl, perhaps, or being visible to her husband–but the screenwriters lack the discipline to develop their characters. The script is missing an adversary, two cranky old ladies and a needlessly antagonistic sheriff (the usually stoic Kenneth Tobey) shoehorned in to imperil the circus. The arrested development Big Top Pee-wee proceeds with might have been a symptom of Reubens & McGrath writing for children’s television, or more likely, exhaustively writing without a break. The entire effort feels tired. Randal Kleiser’s career suggests the vision of his producers–rather than any point-of-view he has to offer as a director–to be paramount, and other than making sure the camera is in focus, puts in pedestrian work, a glaring deficiency following in the footsteps of Tim Burton.

Video rental category: Fantasy

Special interest: Backstage Drama

Wow! Good morning Joe, as I said, before, I never got into the character of Pee-wee, Herman, but after reading your analysis and review and background information, what a total disaster! Yeah, I think I’ll walk barefoot over shards of glass before I see this movie… Thanks for the insight, Joe, as always great information! Peace! CPZ