Beverly Hills Cop

Eddie Murphy becomes a superstar in ragged but lovable ensemble effort

For the remainder of summer Video Days piles in a vehicle and for those who can’t take a vacation, journeys to unfamiliar places with comedies about strangers in strange lands.

BEVERLY HILLS COP (1984) is two movies, both of which work. One is a broad ‘80s comedy with a comic star at what would be his peak. The other movie is a gritty ‘70s cop thriller trafficking in violence. Rather than limp to an inconsistent finish, this scruffy action-comedy making things up as it goes is about a Detroit police detective (played by 23-year-old Eddie Murphy) who’s scruffy and making things up as he goes. The film shines with charisma and good will even when Murphy is off-screen, and is punctuated by swift punches to the gut in its criminal content. The only truly good entry in what would become something of a franchise, it over-delivers.

Like most successes, several people have stepped forward to take credit for the genesis of Beverly Hills Cop. Michael Eisner, installed as president of Paramount Pictures in 1975, claimed he hatched the idea after being pulled over for speeding in the station wagon he’d driven out west from New York, the condescension of the ticketing officer inspiring Eisner to order a movie about L.A. cops. At roughly the same time, an executive being mentored by Eisner named Don Simpson was working with up-and-coming filmmaker Floyd Mutrux on a project about the Mexican Mafia, which would ultimately be produced as American Me (1992), Mutrux credited for story and co-writing the screenplay. Dining with Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department deputies who looked and sounded indistinguishable from hoodlums, Simpson claimed to have hatched the idea for a crime thriller similar to Dirty Harry (1970), about a half-Latino cop draped in tattoos posted to the most incongruous beat in greater Los Angeles for a loose cannon: Beverly Hills.

In 1977, Simpson and Eisner commissioned Danilo Bach to adapt their idea to screenplay. Bach completed two drafts, ignoring most of Simpson’s input and coming up with a protagonist named Elly Axel, a cop from Detroit who travels to Beverly Hills to investigate the murder of his childhood friend, suspecting a successful local businessman of living the double life of a crime kingpin. Out of his jurisdiction, Axel is paired with a by-the-book lieutenant in the Beverly Hills Police Department named Bogomil. Titled Beverly Drive, Bach did follow Simpson’s order for a straightforward cop thriller. Screenwriters William D. Witliff and Vincent Patrick were commissioned to work on the script, but without a director or star, the project failed to move forward. Simpson was ready to drop it until he partnered with the producer of American Gigolo (1980) and Thief (1981) to launch Don Simpson/ Jerry Bruckheimer Films in 1982. Bruckheimer encouraged Simpson that what he referred to as Beverly Hills Cops was the best idea he had. Simpson/ Bruckheimer’s first production, Flashdance (1983), hit big right out of the gate, opening #1 at the U.S. box office for nearly its first month in release, word of mouth holding a spot for it among the top ten grossing films for fifteen weekends.

To write a fresh draft of their cop thriller, the producers turned to Daniel Petrie Jr. Son of director Daniel Petrie, Petrie Jr. had gotten his start working in the mailroom of International Creative Management, but decided he enjoyed writing more than agenting (for a friend named Jim Kouf, who’d author the action-comedy Stakeout). Petrie Jr. left ICM and wrote two scripts on spec. One was a science fiction story, the other a thriller about a corrupt cop who improbably falls for an assistant district attorney. Titled Windy City, the latter was written in 1982 and sold after three days on the market, which may have gotten the attention of Don Simpson & Jerry Bruckheimer as much as the script, reset in New Orleans and produced as The Big Easy (1987). Working from a cheap office in Beverly Hills that gave him a view of the exclusive boutiques, pretentious art galleries and ridiculous image-conscious attitudes of the neighborhood, Petrie Jr’s take on the material was more tongue-in-cheek. Simpson & Bruckheimer agreed they had a movie, which somewhere along the way, had lost its plural tense to become Beverly Hills Cop. Its protagonist now named Axel Eddy, the producers settled on Mickey Rourke, recently of Diner (1982), for the lead. Rourke expressed interest, but efforts to pair the material with a director proved elusive.

Martin Scorsese thought the script derivative of Coogan’s Bluff (1968), in which Clint Eastwood starred as an Arizona deputy sheriff out of his element in New York. David Cronenberg, who made his films exclusively in Canada, wasn’t interested. With an offer on the table, Rourke took a co-starring role opposite Eric Roberts in The Pope of Greenwich Village (1984). Paramount had signed writer/ producer/ director Sylvester Stallone to an overall deal at the studio in the wake of his film Staying Alive (1983), a sequel to Saturday Night Fever (1977) which was no Flashdance but had survived scathing reviews to perform well at the box office. As a mere courtesy, Paramount forwarded the hyphenate the script to Beverly Hills Cop. To the shock of Simpson & Bruckheimer, Stallone wanted to make it his next starring role. For two weeks, the star huddled with Petrie Jr. to share his ideas. Having just wrapped a fish-out-of-water comedy set for release in June 1984, the ill-fated Rhinestone, Stallone backed away from the script’s comic elements and proposed returning Beverly Hills Cop to a high-charged action vehicle. His ideas included a shootout at Neiman Marcus Beverly Hills and a climax in which his character–to be named Axel Cobretti–drove a Lamborghini at the freight train being operated by the bad guy.

To direct, Jerry Bruckheimer had successfully recruited Martin Brest. A graduate of the American Film Institute in 1977, Brest had written and directed a little-seen heist comedy starring George Burns and Art Carney titled Going In Style (1979). Taking some time to decide on his next job, the one Brest chose hadn’t turned out well, United Artists firing him as director of WarGames (1983) after twelve days, the studio displeased that a thriller about global thermonuclear war looked too dark, turning to John Badham, director of Saturday Night Fever, to give the movie more of a pop sensibility. Brest saw potential in Petrie Jr’s script, but shared Stallone’s desire for a tougher movie. While Simpson & Bruckheimer were amenable to script changes, Paramount wanted a reasonably budgeted picture for Christmas 1984, not an over-budgeted one in 1985. The studio gave Stallone a choice: sign off on Petrie Jr’s script, or make his version elsewhere, provided it wasn’t about a cop in Beverly Hills. Stallone opted for the latter, and in October 1985 would begin filming a thriller from his own script titled Cobra (1986), playing a cop named Marion Cobretti who likes sunglasses and taking down scumbags.

With two weeks until production on Beverly Hills Cop was slated to begin in May 1984, Simpson & Bruckheimer received the blessing of studio chairman Barry Diller to travel to New York and offer the lead to Eddie Murphy. Joining the cast of Saturday Night Live in 1980 (as a featured player, not a cast member), the Brooklyn-native became a television star at the age of 19 and jumped immediately into film stardom, co-starring with Nick Nolte in 48 HRS. (1982) and Dan Aykroyd in Trading Places (1983), both pictures new classics. Murphy’s next picture hadn’t gone well, the comic accepting a $1 million offer to participate in the Dudley Moore comedy Best Defense that had tanked in test screenings and inserted Murphy in roughly 20 minutes of new scenes independent of Moore. Eager to book his next job before the release of Best Defense in July 1984, Murphy seized on Beverly Hills Cop, which like all of his films to that point, was being financed and distributed by Paramount. In lieu of a May start date, Murphy’s casting was announced in April. No time for script changes, the only one Murphy suggested was rhetorical, that his character–now named Axel Foley–be twenty-three years old so he could act his age. Murphy’s wardrobe was scaled down to a navy blue zip-up hoodie, high school gym sweatshirt, blue jeans and white Adidas sneakers. He also took to tucking his prop .45 pistol into the back of his waistband, just like Gilbert R. Hill, the Detroit homicide detective serving as technical consultant (Hill would be cast as Axel’s temperamental boss, Inspector Todd, out cursing and out acting Murphy in their two scenes together).

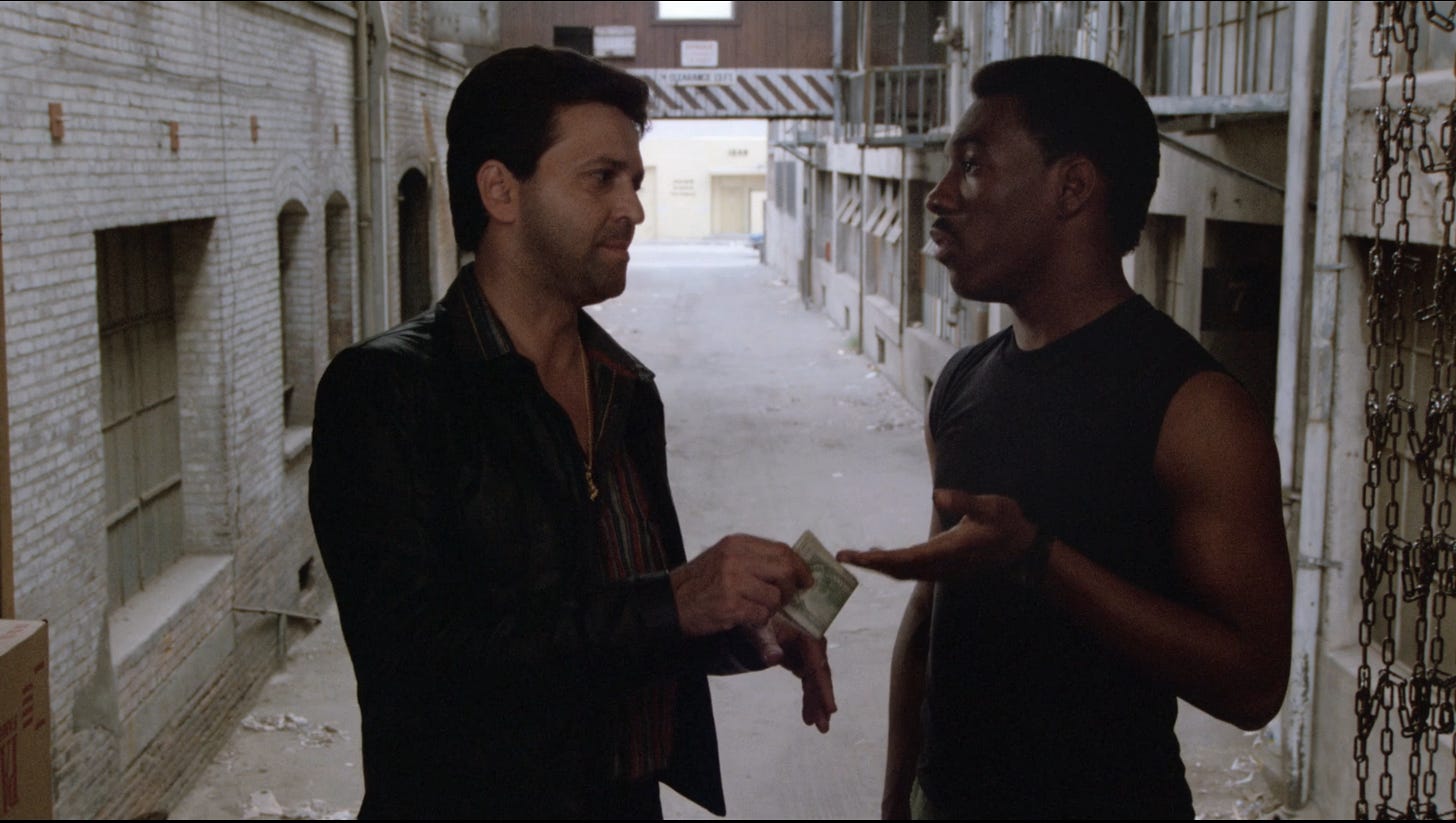

Beverly Hills Cop was shot in Los Angeles in the summer of 1984. Aware of their looming release date and that his career would be over if he gave another studio a reason to dismiss him, Brest would deliver the $15 million picture under-budget, closer to $13 million. Director of photography Bruce Surtees had worked for Don Siegel (beginning on Dirty Harry in 1971) and extensively for Siegel’s protégé Clint Eastwood when the actor launched his directorial career, with Play Misty For Me (1971). Siegel and Eastwood were known for their frugality, and Beverly Hills Cop was shot similarly: fast and loose. Brest raised no objection to Eddie Murphy riffing on Axel’s dialogue where they felt the script needed it, such as the scene where his character talks his way past a maître d'. The opening scene–in which Axel has gone undercover to sting buyers of stolen cigarettes–was filmed in the Wholesale District downtown, off Palmetto Street. Exteriors for Foley’s apartment were done in DTLA, off 7th Street on a block that looked more like Detroit at that time. Also downtown, the historic Biltmore Los Angeles stood in for the “Beverly Palms Hotel,” presumably renamed so no one would think guests were welcome to steal the Biltmore’s bathrobes. The “Hollis Benton Art Gallery” where Axel meets Serge (Bronson Pinchot) was shot on Rodeo Drive, but the “Harrow Country Club” where Foley confronts Victor Maitland (Steven Berkoff) and his henchman Zack (Jonathan Banks) is a private club on the campus of the California Institute of Technology in Pasadena. Exteriors for the bad guy’s Mediterranean-styled villa–including the shootout on the grounds–were shot at an estate in the canyon between Santa Monica and Pacific Palisades. Interiors for Maitland’s mansion were filmed in Castillo del Lago, a Mediterranean-style estate in the Hollywood Hills which Madonna purchased in 1993. A second unit crew was dispatched to Detroit to shoot the opening title sequence and cigarette truck chase.

Seven months after it started filming, Beverly Hills Cop was in theaters, opening December 7, 1984 in what was at that time a huge number of houses: 1,542 in the U.S. Paramount was so confident they opened their holiday release against two of the more anticipated movie events of the year: 2010, MGM/UA’s action-oriented sequel to 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and City Heat, a period action-comedy from Warner Bros. pairing Clint Eastwood and Burt Reynolds. Beverly Hills Cop doubled the ticket sales of either in its opening weekend and was the #1 movie in the country for a staggering fourteen of its first fifteen weekends in release. Audiences kept Beverly Hills Cop among the top ten earning films in the country for seven months, and it would finish the highest grossing R-rated film made up to that time. The soundtrack album flew off shelves, three tracks–”The Heat Is On” performed by Glenn Frey, “Neutron Dance” by The Pointer Sisters and “Stir It Up” by Patti LaBelle–featured prominently in the film, while the electronic score by Harold Faltermeyer would spawn a top 40 hit with “Axel F.” (The song licensed for the strip club scene, “Nasty Girl” by Vanity 6, was omitted from the soundtrack).

The interesting thing about Beverly Hills Cop that separates it from most of the era’s comedies–many of which, like this one, drew talent from Saturday Night Live or National Lampoon, occasionally both–is that it wasn’t drawn up as a comedy. Its roots are in ‘70s pulp fiction, and the film has the scruffiness but also charm of a dimestore paperback: an inescapable title, lurid violence, incessant profanity and broken spine. Everything about the plot is disposable. For reasons that defy explanation, a Eurocentric art dealer (played by villain du jour Steven Berkoff with a nastiness only hinted at in the text) smuggles cocaine and has enemies terminated by his henchman (Jonathan Banks, who’d become an overnight success thirty years into his acting career as a nuanced and terrifying henchman, Mike Ehrmantraut on the TV series Breaking Bad and Better Call Saul). The drug smuggling material is reminiscent of what was playing on television every Friday night with Miami Vice, but ironically, the show would only take off in the ratings in reruns between Seasons 1 and 2, the moment Beverly Hills Cop ended its theatrical run, the fashion and pop music sensibility of Simpson & Bruckheimer appearing to set the table for Miami Vice rather than the other way around, Glenn Frey even hopping from the soundtrack for Beverly Hills Cop to the one for Miami Vice.

The key isn’t the material but how the cast and the director adapt the material. In navigating how to be an actor or carry his own movies, Eddie Murphy lucked into a part about a kid navigating how to be a detective or carry his own investigations. Like Madonna in Desperately Seeking Susan (1985), Murphy was a new superstar playing himself, his ceiling as an actor appropriate for his character. Some of Murphy’s riffs are needlessly antagonistic (raising his voice and accusing a female clerk of racism to book a hotel room, or badgering customs officials who are similarly just doing their jobs) but they work because when over his head, Axel would resort to being a jerk too. Murphy’s empathy is so winning that like an older brother with a car, we hope he allows us to tag along to wherever he’s going, and Beverly Hills Cop retains an abundance of good will. The casting–by Margery Simkin, who cast Ladies and Gentleman, the Fabulous Stains (1982) and The Flamingo Kid (1984) and would be retained by Simpson & Bruckheimer for Top Gun (1986)--really saves the movie, which in addition to Banks, landed Judge Reinhold and John Ashton as Axel’s detective contemporaries in Beverly Hills, Rosewood & Taggart, and Ronny Cox as Lt. Bogomil, who rather than a heel, is directed by Martin Brest to play his character as strict yet competent. Instead of stooges dumbed down to make the star look good, these characters are ultimately good at their jobs, extending Axel the professional respect he deserves to convince them he’s uncovered something illicit.

Paul Reiser, Damon Wayans, Rick Overton, and most memorably, Bronson Pinchot–who parlayed two scenes as a vaguely European art dealer into seven seasons playing a vaguely European villager on the sitcom Perfect Strangers–reduce the need for Murphy to initiate every laugh. His youth, vigor, and irreverence lighten the tone in a way Sylvester Stallone would never have, the proof being how vacuous Cobra is. While most of the dialogue was scripted–the WGA awarding screenplay credit to Daniel Petrie Jr. and story credit to Danilo Bach and Petrie Jr.–Ashton would not have broken into the grin he does during Murphy’s “super cops” testimonial if performing that scene with Stallone. In what seems negligent, Axel is denied a romantic interest, but rather than play like an oversight, this actually adds complexity to his sexual orientation. Murphy’s bar scene with James Russo (as Axel’s childhood pal Mikey) is so intimate the two actors seem close to kissing at any moment. Paramount’s reluctance to damage the appeal of their biggest star by allowing Murphy to play an interracial romance (with Lisa Eilbacher, the weakest link in the cast as Axel’s childhood friend, Jenny) generates an unintentional but unmistakable homosexual undercurrent. Returning to his hotel room with Jenny, Axel seems more interested in talking about Mikey than acknowledging Jenny, who’s throwing herself at him. It’s accidents like this that help make Beverly Hills Cop rewatchable, and with the exception of Eilbacher, everyone tangentially involved in the picture got more film work as a result.

Video rental category: Comedy

Special interest: Stranger In A Strange Land

Hey, good morning Joe! Beverly Hills Cop was so much fun for what appears to be impromptu, quick line zingers, and improvisation… Each scene was entertaining, so much so that, I really didn’t pay much attention to plot or the improbability of each scene… As always, your background information is so enlightening… My God, all of the talent that flows in and out of a movie being made … directors, writers, actors that have proven blockbusters elsewhere, being accepted or rejected until the right witches brew comes together and produces a winner… It’s truly amazing as to how that happens, and what ultimately is the end result … thanks for this one, Joe, your critiques analysis and background information is always so much fun and entertaining! Peace! CPZ