Back to the Future at 40

Crackerjack screwball sci-fi comedy the imperfect time travel classic

For the month of July, Video Days piles in a vehicle and for those who can’t take a vacation, journeys to unfamiliar places with four comedies about strangers in strange lands.

BACK TO THE FUTURE (1985) is the best time travel movie ever made, and in forty years, no other filmmaker has really been able to top it. An expertly written situation comedy that blends slapstick and science fiction in delightful and exciting ways, its novelty wasn’t necessarily jokes or special effects–though the film has plenty of memorable ones–but a time traveler who was flunking science rather than mastering it. Because teenagers are more focused on sex, this leads the movie, which is far from perfect, down fresh and exciting paths.

Robert Zemeckis and Bob Gale met at the University of Southern California in 1971. Enrolled in the School of Cinematic Arts, they were midwesterners who held no pretension for art film, but bonded over what they’d grown up watching: Clint Eastwood, James Bond and Walt Disney. They wanted to make movies for Hollywood. After they graduated, “the Bobs” co-wrote a script set in a vampire-operated whorehouse titled Bordello of Blood. They followed this up with more outrageousness, an action/ comedy about dissidents who steal a Sherman tank and threaten to blow up a Chicago skyscraper. Writer/ director/ military historian and USC alumnus John Milius was interested enough to hear what else the duo was working on, and they ultimately pitched Milius a movie based on the so-called Battle of Los Angeles, in which the Office of Naval Intelligence warned L.A. that an air raid by the Japanese was imminent. In an ensuing five-hour blackout on February 24, 1942, chaos reigned throughout the city. When Steven Spielberg heard about the Zemeckis & Gale script from his friend Milius, the director of Jaws (1975) and Close Encounters of the Third Kind (1977) asked if he could direct it, to everyone’s surprise. Referred to for months prior as The Night The Japs Attacked, the movie would be retitled 1941 (1979) and open to the worst press of Spielberg’s career, prompting him to conclude that comedy wasn’t his forte.

Despite some dismal reviews and the modest box office take of 1941, Spielberg continued to mentor Zemeckis & Gale. He served as executive producer on Zemeckis’ directorial debut, I Wanna Hold Your Hand (1978), another comedy about mass hysteria, this time in New York during the Beatles’ appearance on The Ed Sullivan Show in 1964. Zemeckis co-wrote the script with Gale, as he would his next picture as director, using a used car dealership in Arizona to stage the hijinks of Used Cars (1980). Steven Spielberg and John Milius served as executive producers on the latter, but it would take repeated viewings on cable television or videocassette for either film to build an audience. Rummaging through boxes in his parents’ basement in St. Louis, Gale found his father’s high school yearbook, where he discovered that his dad had been president of his graduating class. Gale belonged to the generation that had led the charge to abolish student government, and wondered whether he’d have related to his father at all if they’d crossed paths as teenagers. Gale returned to Los Angeles and shared his epiphany with Zemeckis, who thought his writing partner had the basis for a clever time travel story: a teenager goes back in time and meets his parents as teenagers.

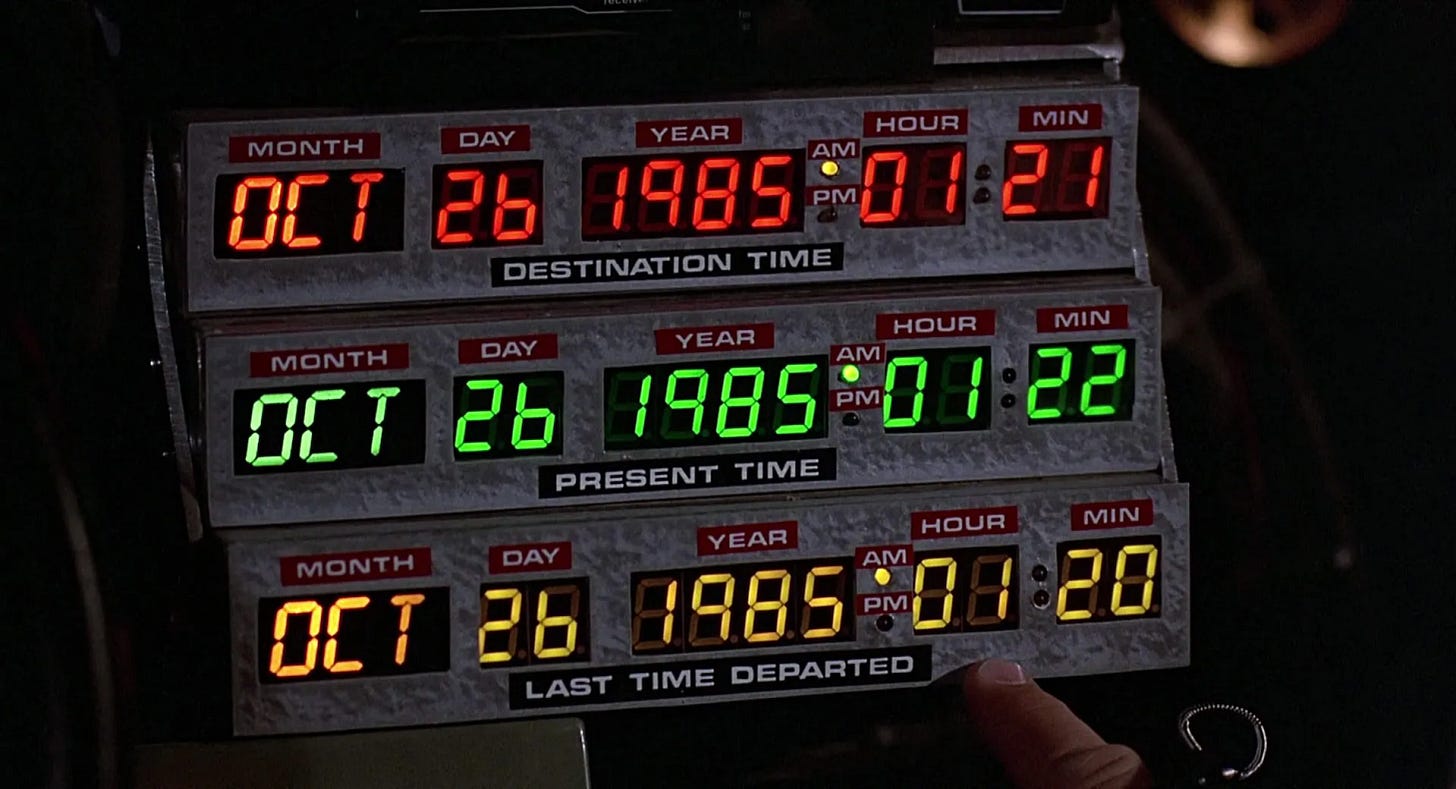

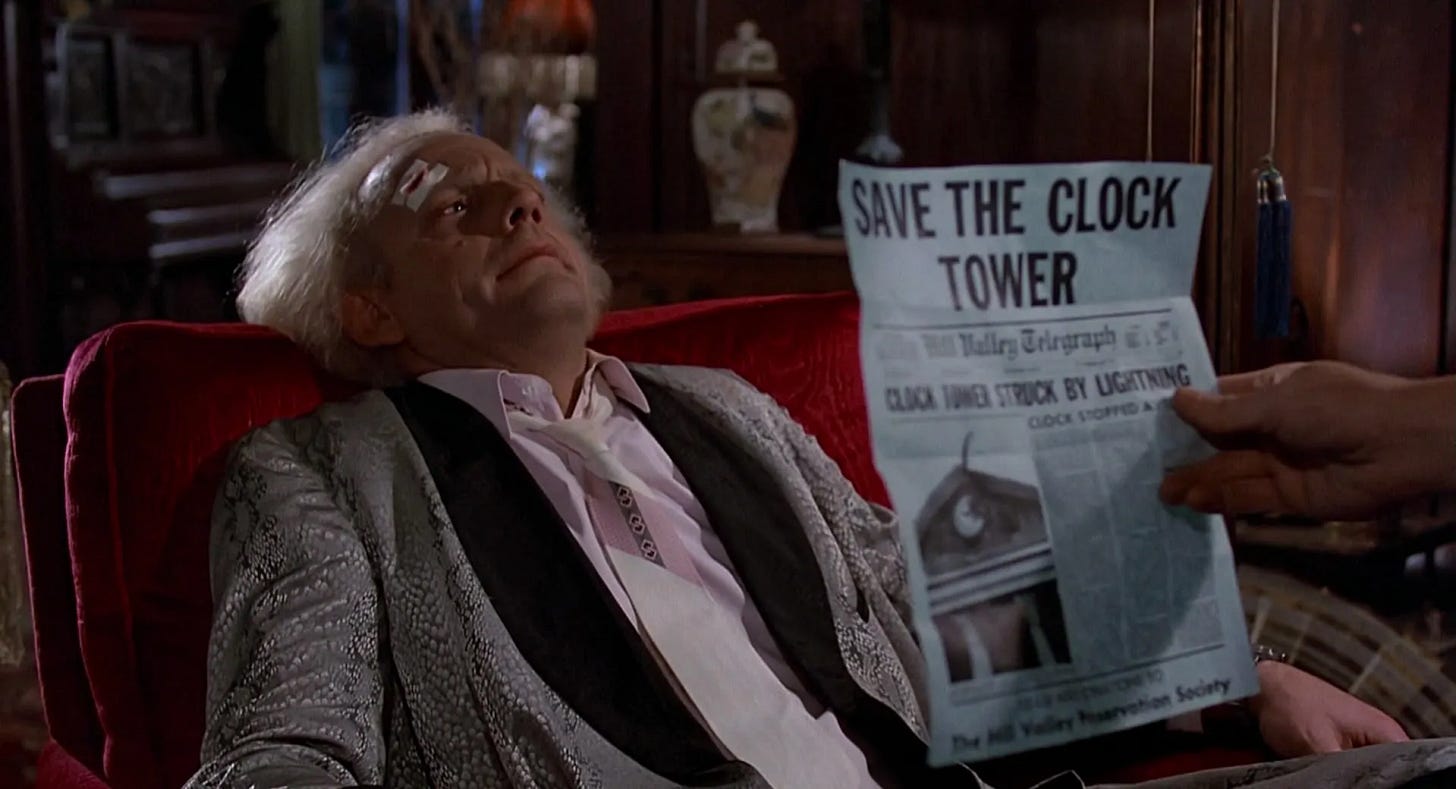

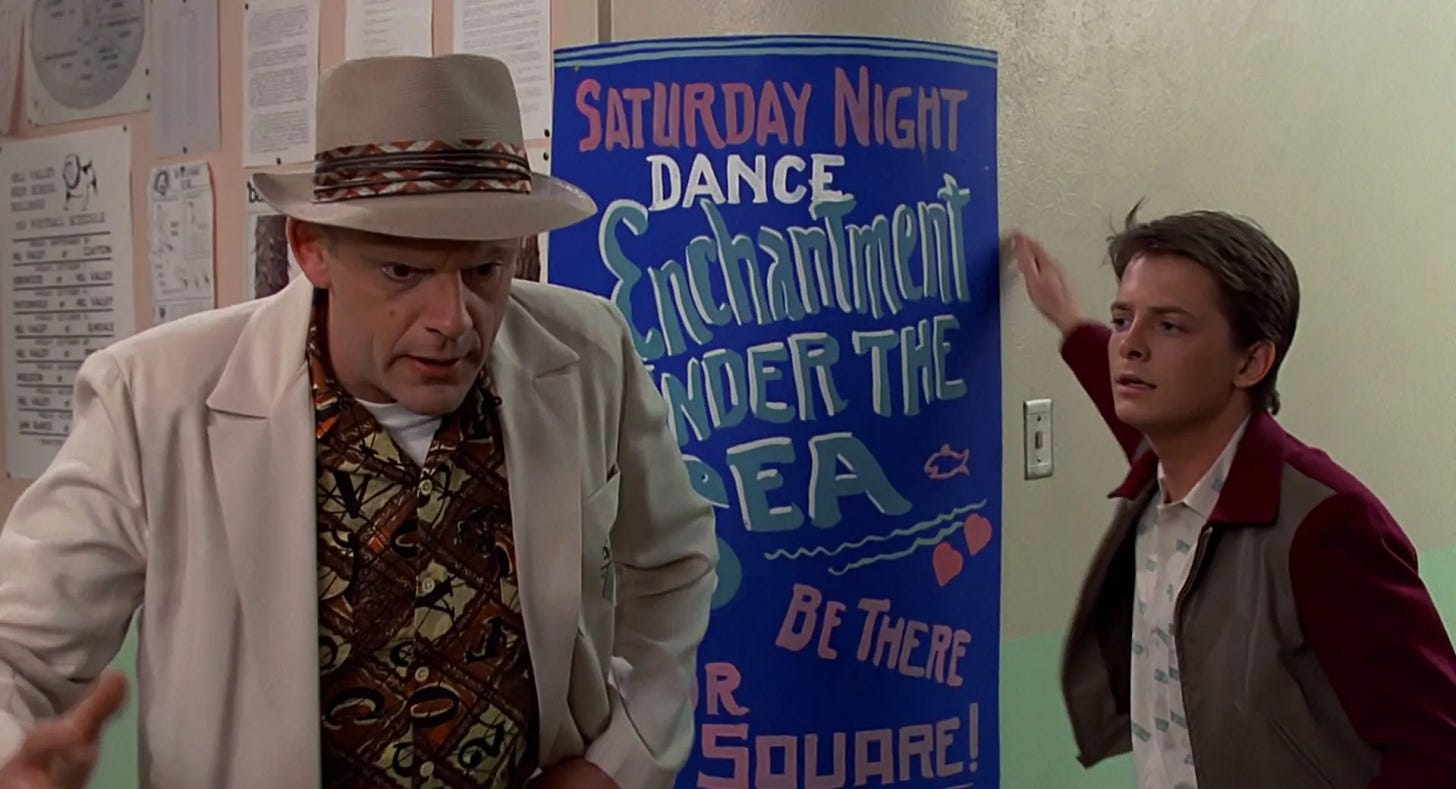

Zemeckis & Gale began writing Back to the Future in September 1980. In their first draft, the time machine resembled a car wash, which Marty McFly, driven to suicide, steps into because he belives the contraption will electrocute him to death. The writers later hit on the idea of the time machine being a car, a vehicle capable of achieving dangerously high speeds, but unlike K.I.T.T. of TV’s Knight Rider, possesses some charm or eccentricity. They chose an ‘81 DeLorean, solidifying the notorious American automaker John DeLorean a foothold in popular culture forever. Early drafts climaxed with their time traveling teenager Marty McFly driving the DeLorean through an atomic test in Nevada and using the explosion to get back to the future. Considered cost prohibitive, Zemeckis & Gale arrived on harnessing a bolt of lightning as it strikes Hill Valley’s old clock tower, which connected their climax with the clock motif they’d established. Virtually everyone the Bobs pitched Back to the Future to in the early 1980s passed on it. Neither Time After Time (1979) or Somewhere In Time (1980) had set the box office on fire, nor had I Wanna Hold Your Hand or Used Cars, a toxic combination.

Horny teenager movies like Porky’s (1981) were in vogue, whereas Marty McFly was considered too wholesome by executives at every studio except Walt Disney Productions, which deemed Marty traveling through time to fend off the amorous advances of his mother too racy. The only champion of the script was Steven Spielberg. Zemeckis & Gale were wary of cementing a reputation for being unable to work with anyone but Spielberg, and Zemeckis pledged to take a job as a director-for-hire on the next interesting project that came along. This turned out to be Romancing the Stone (1984) with Michael Douglas both producing and stepping into the top-billed role. Twentieth Century Fox was so sour on the finished picture’s commercial prospects–finding its protagonist Joan Wilder (Kathleen Turner) unlikable–that they dismissed Zemeckis from developing Cocoon (1985), replacing him as director with Ron Howard. When Romancing the Stone not only opened to strong ticket sales but held a spot among the top ten grossing films in the U.S. for three months, Zemeckis found the film industry receptive to whatever he wanted to do next.

To produce Back to the Future, Zemeckis chose the only person who’d expressed faith in the project, Steven Spielberg coming aboard as executive producer (with Kathleen Kennedy and Frank Marshall) via Amblin Entertainment. Universal Pictures agreed to finance and distribution. Gale would recall Sid Sheinberg, president and CEO of MCA/ Universal and Spielberg’s mentor, giving the screenwriters only three notes: No one should call Dr. Emmett Brown “professor” because it sounded stuffy, Doc would not have a pet chimpanzee because no movie with a chimp had been successful, and the title Back to the Future had to go. Neither Doc’s educational background or the possibility he’d been a tenured professor would be mentioned in the film or its sequels, but Gale argued that Every Which Way But Loose (1978) and its sequel paired Clint Eastwood with a monkey, to which Sheinberg retorted that had been an orangutan, not a chimp. With Spielberg’s support, Zemeckis & Gale ignored the studio chief’s request to come up with a new title.

The filmmakers’ first choice to play Marty McFly was Michael J. Fox, unavailable due to his commitment to the NBC sitcom Family Ties, which would be recording its third season. The two runners-up were C. Thomas Howell and Eric Stoltz, both of whom screen tested for the part of Marty. Gale remembered Howell–who’d appeared in The Outsiders (1982), E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial (1982) and Red Dawn (1984)--giving an excellent audition, but Sheinberg throwing his support behind Stoltz, soon to be seen as a cheeky teenager in Universal’s drama Mask (1985) opposite Cher and Sam Elliott, albeit under heavy makeup. Stoltz won the role. The filmmakers considered offering John Lithgow the part of Doc Brown, but like Fox, he was unavailable. The film’s producer, Neil Canton, who’d produced The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai: Across the 8th Dimension (1984), suggested one of Lithgow’s co-stars, Christopher Lloyd, for the part. Lea Thompson and Crispin Glover were cast as Marty’s parents, and Melora Hardin as Marty’s girlfriend, Jennifer. To play the time machine, the production found three DeLoreans through the personal ads, which vehicle construction coordinator Michael Schaffe modified with items picked from industrial surplus stores, and production designer Lawrence G. Paull souped up.

Back to the Future commenced filming in November 1984 at Universal Studios in Los Angeles. Five or six weeks into production (recollections vary), Zemeckis invited Spielberg to the screening room at Amblin’s offices on the Universal lot to screen 45 minutes of the picture cut together. Zemeckis wasn’t sure if it was just him, or Stoltz wasn’t delivering on the slapstick of their script. Spielberg confirmed Zemeckis’ concerns: the footage wasn’t very funny. Before he created Family Ties, Gary David Goldberg had been commissioned by Kennedy and Spielberg to write a musical the director had planned on making after Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981), and all were good friends, Spielberg the first person Goldberg had screened the pilot of Family Ties for. Spielberg proposed working around Michael J. Fox’s television schedule in order for him to take over the role of Marty. This mandated Fox being shuttled between Paramount Studios in Hollywood for Family Ties by day to Universal Studios for Back to the Future at night, shooting interiors or nocturnal exteriors late into the morning, daylight exteriors to be picked up on weekends. Melora Hardin, 5’7”, could see over the top of Fox (5’4”) and was replaced by the filmmakers’ original choice for the role: Claudia Wells, whose commitment to an ABC sitcom called Off the Rack had proven short-lived.

Considering its bumpy production, Universal’s expectations for Back to the Future were not high. For the first of two test screenings (in San Jose, California), the recruited audience was told nothing more than they’d be watching a new movie with Michael J. Fox and Christopher Lloyd, two television stars in an era when crossover between film and TV was rare for lead actors, who worked in one or the other. Replacing Eric Stoltz had pushed the release back to at least mid-August 1985. By the time the lights went up in San Jose, Spielberg remembered the screening as being the most jubilant he’d attended, with the exception of showing E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial to a test audience in Houston. Those in attendance laughed or applauded through each of the big set pieces. Screened for Universal executives in late April, Sheinberg was ecstatic enough to propose moving the release date for Back to the Future up to the July 4th weekend. Working around the clock with animators and technicians at Industrial Light & Magic to complete the special effects, Zemeckis finished Back to the Future in time for it to open Wednesday, July 3, in 1,341 theaters in the U.S.

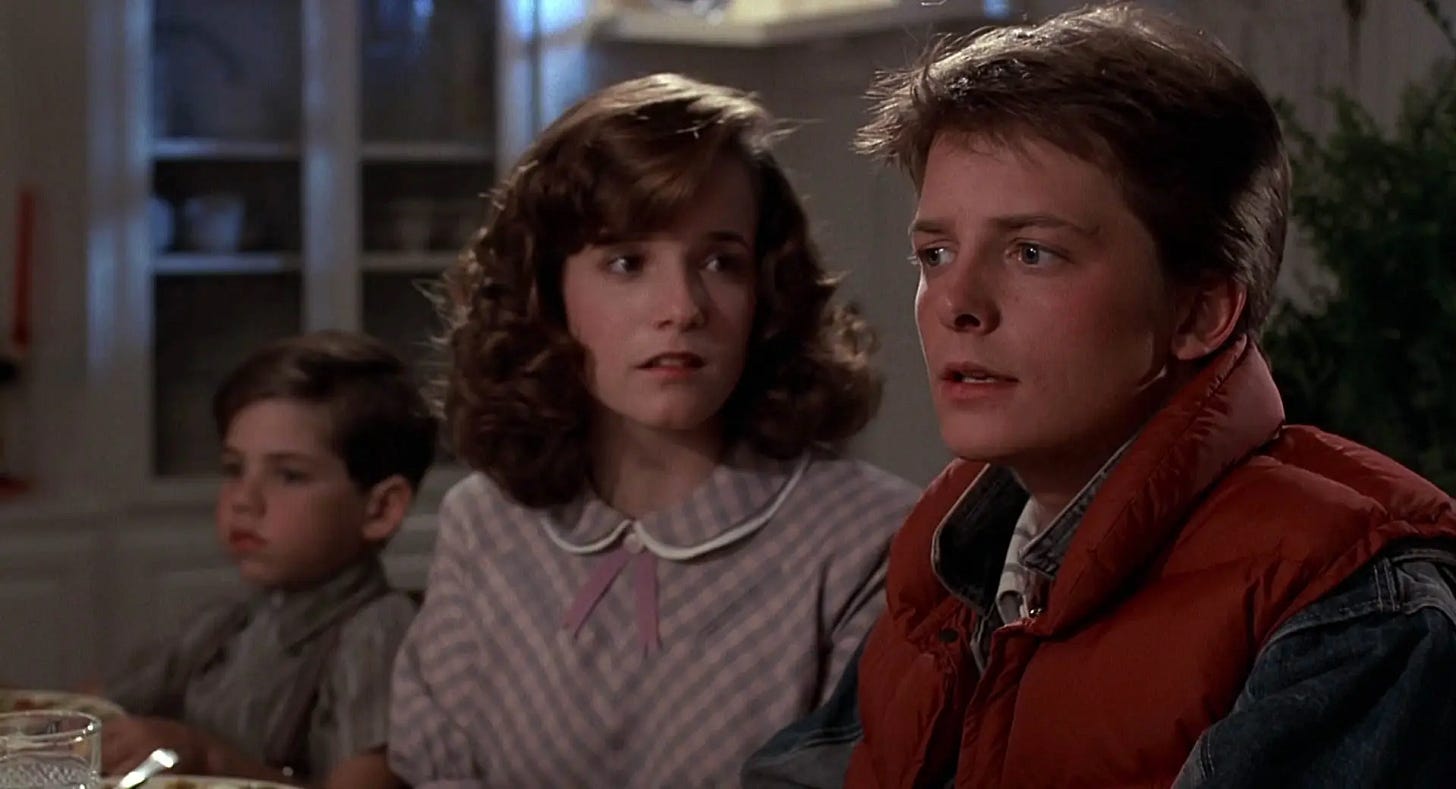

Critical reception to Back to the Future leaned positive. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert gave it two thumbs up. Siskel credited Zemeckis for rejecting action movie staples and possessing the sensitivity and intelligence to make something bigger, going as far as saying that the director and stars of the dog-of-the-week, the sword and sorcery picture Red Sonja starring Brigitte Nielsen, couldn’t have ruined the script by Zemeckis & Gale. Siskel gave it his highest recommendation and would rank Back to the Future #9 on his year-end list of the year’s ten best films. Ebert was thrilled by the film’s conceit of children who can’t imagine their parents ever being young and grown-ups who don’t realize they’ve grown old. He drew a comparison between Back to the Future and a fantasy with a Capraesque touch, namely It’s A Wonderful Life (1946). In her prophetic write-up for the New York Times, Janet Maslin declared: “In less resourceful hands, the idea might have taken an uncomfortable turn, since the story’s young hero must face the transformation of his plump, stern, middle-aged mother into a flirtatious young beauty. But Mr. Zemeckis is able to both keep the story moving and to keep it from going too far. He handles Back to the Future with the kind of inventiveness that indicates he will be spinning funny, whimsical tall tales for a long time to come.” In a studied response for the New Yorker, Pauline Kael offered, “ … Back to the Future is ingenious; it has the structure of a comedy classic, and it’s consistently engaging. If I can’t work up much enthusiasm for it, it’s because I’m not crazy about movies with kids as the heroes–especially bland, clean-cut, nice kids like Marty.”

Kael withheld proclaiming Back to the Future a comedy classic due to Zemeckis & Gale’s “thinking here is cramped and conventional,” offering a vision of America’s past drawn largely from Life magazine and proposing that happiness in the ‘80s was the Yuppie ideal of buying stuff. The strongest commercial competition Back to the Future faced over the Fourth of July was, ironically, Cocoon, then in its third weekend of release, as well as Clint Eastwood’s new western Pale Rider in its second weekend, and Rambo: First Blood Part II, held over from Memorial Day weekend. Two action/ adventures—The Emerald Forest and Red Sonja—accounted for the only new releases. In a box office tally that wasn’t close, Back to the Future opened the #1 grossing film in the U.S. and would remain so for eleven of its first twelve weekends of release. It held a spot among the top ten grossing films in the country through the post-Thanksgiving weekend and ran away as the highest grossing movie of 1985. Zemeckis & Gale completed the picture without weighing the likelihood of a sequel, its send-off just another joke, but when Back to the Future was released on home video in December 1986, a graphic following the film’s final shot had been added, promising “To Be Continued.” The blockbuster would be, Zemeckis & Gale’s tandem script for Back to the Future Part II (1989) and Back to the Future Part III (1990) going into production in February 1989 with Zemeckis at the helm shooting the sequels back-to-back.

As an entertainment delivery system, Back to the Future is military grade in its efficiency. Like Walt Disney, its artistry comes from how dutifully it enthralls the viewer. There isn’t a moment that doesn’t advance the story in some keen way. Every line of dialogue, every plot point, every sight gag is engineered to pay off. Rather than just act on the viewer with lots of gags (ILM visual effects art director Phillip Norwood and visual effects supervisor Ken Ralston among the animators and technicians), the screenplay by Robert Zemeckis & Bob Gale finds another gear by asking us to participate with it. The screenplay not only gives Marty two puzzles to solve–fixing the time machine and matchmaking his parents, both necessary for him to have a future to return to–but slips us clues along the way. We remember Lorraine’s story about falling in love with George when her father hits him with the car and realize Marty is in trouble when he gets hit instead. We remember the volunteer telling Marty the tale about the clock tower being struck by lightning in 1955 and figure that’s how Doc can anticipate where lightning will strike. Back to the Future functions like an interactive game, but it’s not, it’s just great screenwriting. One of the reasons it’s aged so well along with Clue (1985) is that both movies are fun to riddle out, even after one viewing.

Repeat viewings of Back to the Future reveal less than flattering details. Marty doesn’t really travel to 1955. He travels to a movie set, in which every inch of “Hill Valley” has been fabricated on Courthouse Square of the Universal Studios backlot. Michael J. Fox, a superb light comedian whose training on television taught him to think and work very fast, knows how to hold for a laugh better than Eric Stoltz, but wasn’t asked or doesn’t know how to play a teenager, like Stoltz committed to. This adds up to a movie that sometimes looks and feels like TV: The Wonderful World of Disney’s Family Ties. Among the jokes, there’s a tacky one that suggests Marty invented rock ‘n roll, as if Chuck Berry needed his cousin Marvin to jam with a time traveling white boy to inspire Berry’s innovations in rhythm and blues. Then there’s the ending, in which Lorraine and George are reborn as Yuppies. Like the Chuck Berry joke, this gets a huge laugh, but suggests that the rewards of time travel would mainly be material, with new home decor trumping the sobriety Marty’s mother has discovered or the self-respect his father has developed. Christopher Lloyd is asked to hit one note as Doc Brown, repeating “Great Scott” when once would’ve been enough, but Lea Thompson and Crispin Glover–so good-looking that they would rarely be hired for comedy–are hysterical. Unlike Lloyd, playing a stock mad scientist, Thompson and Glover create unique characters, finding oddball mannerisms in the way Lorraine and George talk or walk. Back to the Future is a reminder that Zemeckis was once known for his outrageous sense of humor. Soon to be associated with cutting edge special effects in movies like Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988), Death Becomes Her (1992) and Forrest Gump (1994), the central dilemma in Back to the Future is a mother lusting after her teenage son. The film is so expertly made that it’s easy to forget about the Oedipal complex staring at us the whole time.

Video rental category: Science Fiction

Special interest: Stranger In a Strange Land

Excellent read! As usual :) TY Joe.

Hey Joe, good morning! I loved all three installments of back to the future, it was just so much fun… All the characters were just the best, and I can’t imagine Eric Stoltz or any other actors playing the main characters. Your background information and analysis, as always, it’s just the best, thank you … always informative and entertaining… Peace! CPZ