Another Woman

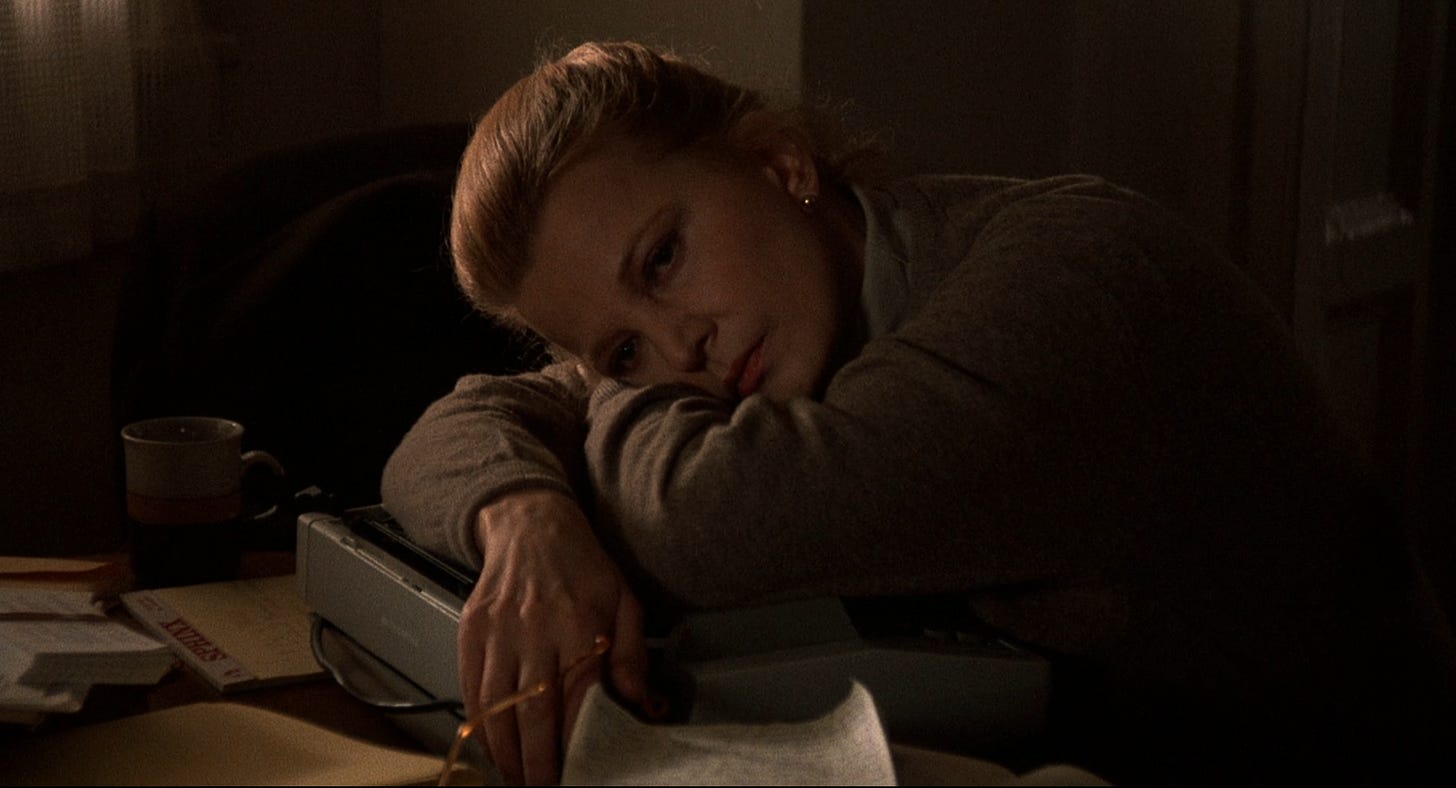

Gena Rowlands confronts dream and memory in overlooked gem

Standup comic/ actor/ writer/ director Woody Allen was born on November 30, 1935 in the Bronx, NY. To celebrate his 90th birthday, Video Days returns to his third decade of work this month with ten films from the master filmmaker.

ANOTHER WOMAN (1988) is on a short list of overlooked gems by Woody Allen. In a career spanning fifty feature films as a writer/ director, few would make the smaller yet potent impact of this one. Written and directed but not starring Allen, this drama takes numerous cues from Wild Strawberries (1957), one of the best pictures from one of Allen’s icons, Swedish director Ingmar Bergman. While leaning more tragic than comic, the film is elegant, with a beguiling premise that elicits charged performances and builds very credible suspense.

In Woody Allen By Woody Allen, the 2005 book of conversations with author Stig Björkman, the filmmaker recounted the genesis of what became his eighteenth film. “Many years before I wrote the story of Another Woman, I started to think about a comedy where I would be in an apartment and through the heating vent would hear what was going on in the apartment below me. And what I heard was a psychiatrist treating patients. He starts to treat a woman and she talks about her most intimate secrets. And I look out the window, because I hear her talking, and I see that she’s beautiful. So I run downstairs and I contrive to meet her. I know exactly what she dreams of in a man and what she wants, and I make myself that person. I thought about that idea for a while. I had it and I kept it. Then one day I said to myself, ‘Wouldn’t it be interesting to use this idea in a dramatic movie? With a woman overhearing a conversation in a neighboring apartment. But what kind of a woman would that be?’ And I thought, ‘What if it’s a woman who is strong intellectually but blocked out in her feelings? And she comes to realize that her husband is having an affair, that her brother doesn’t really like her, that her friends don’t really like her.’ She would be a philosophy teacher but she has kept everything personal in her life totally blocked out. And she finally reaches a point, where she can no longer block out things in this way. They literally start to come through the walls, the sounds of her inner turbulence start to come through the walls to speak to her. So that’s how it started.”

Allen had never started a proper script when it was potentially a comedy for him to star in. Reconceptualized as a drama, Allen wrote the lead roles with Mia Farrow and Dianne Wiest in mind, the actors having played friends in September (1987) and sisters in Hannah and Her Sisters (1986). Pregnant with Allen’s child, Farrow might have bowed out of the more demanding role of the philosophy teacher due to her maternity, while Wiest–heavily in demand after winning an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress in Hannah and Her Sisters–was recuperating between jobs and unavailable. After considering Jane Alexander, who Allen had wanted to work with on Interiors (1978) before casting Diane Keaton instead, Farrow was cast as the unnamed woman (listed in the credits as Hope) whose anguish drifts through the vent of an old brownstone which the teacher has subleased to begin writing a book. Allen rewrote the role of the teacher for an actress in her fifties, and his first choice was Gena Rowlands. Allen had approached Rowlands about playing the show business legend and mother in September, but she hadn’t been able to get a bead on that character. The Academy Award nominee for Best Actress in A Woman Under the Influence (1974) had no such difficulty with Marion Post.

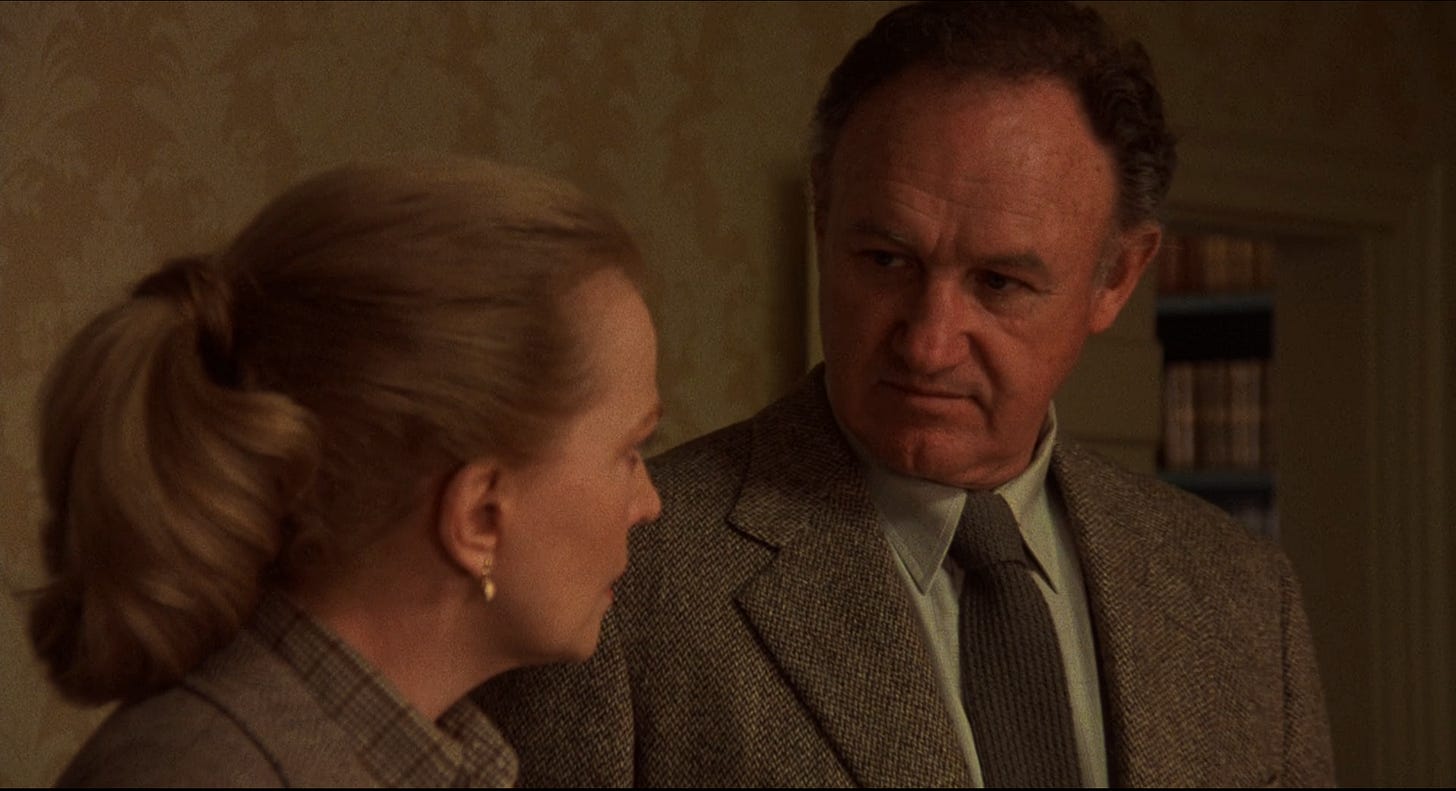

With the exception of Mia Farrow, the cast of Woody Allen Fall Project 1987 were working with the filmmaker for the first time. To play opposite Gena Rowlands as Marion’s husband, Ken, Allen saw the character as a Ben Gazzara type, as he had with the part Max Von Sydow would play in Hannah and Her Sisters. Allen again abandoned the notion of casting Gazzara and went in the opposite direction with Ian Holm (5’5”). Gene Hackman was cast as Ken’s friend, a novelist, who met Marion when she was Ken’s mistress and has been in love with her since. With five movies set to be released in the fall of 1988, including Bat*21 (10/21), Split Decisions (11/11), Full Moon in Blue Water (11/23), and Mississippi Burning (12/9), Hackman was credited by Daily Variety as nearly the busiest actor in film, Steve Guttenberg at #1. Martha Plimpton was chosen to play Marion’s sixteen year old stepdaughter, who admires Marion and respects Marion but doesn’t necessarily love Marion. Blythe Danner was cast as a married friend of Marion and Ken’s, Harris Yulin (who’d dropped out of Interiors to be replaced by Sam Waterston) as Marion’s wayward brother, Mary Steenburgen as Marion’s sister-in-law, and in his last film role, John Houseman as Marion’s father, an esteemed historian. Houseman had been a theatrical producer in the 1930s, giving Orson Welles his early work as both a stage actor and later, director. Forty years later, Houseman won an Academy Award for Best Supporting Actor in virtually the first movie he’d acted in–The Paper Chase (1973)--and spent the last fifteen years of his life in demand as an actor and commercial pitchman.

Allen’s script took more cues from the work of his filmmaking idol Ingmar Bergman than any he’d completed thus far. While Bergman’s film Wild Strawberries concerned a retired medical professor in his seventies who assesses his past while on a road trip to receive an award from his former university, Allen’s variation was at least told in a similar manner, utilizing voiceover narration by an academic who has isolated herself from meaningful human contact and whose dream life begins to inform her waking life. To serve as director of photography, Allen hired Sven Nykvist, who’d lit some of Bergman’s more notable films: Persona (1966), Cries and Whispers (1972), Fanny and Alexander (1982). Filming commenced in October 1987. The building where Marion bumps into her childhood friend Claire (Sandy Dennis) and later visits in her dream was the Cherry Lane Theatre in Greenwich Village, the oldest off-Broadway house in New York. The bar where Marion and Claire hold their tense reunion was Chumley’s, a speakeasy also in the Village. Unhappy with how he’d written and directed her scenes, Allen would reshoot those involving Mary Steenburgen, but with the actor unavailable due to her commitment to Miss Firecracker (1989), he recast Frances Conroy in the part, which would be trimmed in the editing room to one scene opposite Rowlands.

Orion Pictures opened Another Woman on October 14, 1988 in New York and Los Angeles. While commercial demand for the picture never expanded beyond 24 screens in the U.S., critics leaned positive. Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert gave the film two thumbs up. For his column in the Chicago Tribune, Siskel wrote: “The situation could’ve been played for comic effect, but writer-director Allen, who doesn’t appear in the movie, is deadly serious here, and Rowlands’ heartbreak is real. Listening to people question their choices stimulates a chain reaction–in the movie and, one suspects, in the audience.” Siskel gave Another Woman three stars. Writing in the Chicago Sun-Times, Ebert added: “Allen’s film is not a remake of Wild Strawberries in any sense, but a meditation on the same theme: the story of a thoughtful person thoughtfully discovering why she might have benefitted from being a little less thoughtful.” Ebert gave Another Woman his highest rating, four stars. Vincent Canby doled out the most criticism in the New York Times: “Mr. Allen is becoming an immensely sophisticated director, but this screenplay is in need of a merciless literary editor. It’s full of an earnest teen-age writer’s superfluous words, in addition to flashbacks and a dream sequence that contain material better dealt with in the film’s contemporary narrative. Mr. Allen’s literary references (to Rilke here) stand out like sore thumbs, though they are endearing as the expressions of an artist who appreciates knowledge and the process of acquisition. It’s meant as admiration to say that Mr. Allen has never grown up.”

At the time of its release, Another Woman was appraised as another dramatic overreach from a comic director who was, at best, imitating his idols, not doing the work he was “meant” to do. What no one could accuse Allen of here was repeating himself, or making a boring movie. Another Woman is neither Woody Allen or Ingmar Bergman, but both filmmakers, written and cast superbly. As a result, it’s invigorating throughout a perfunctory 81 minute running time. For the first time, Allen jumps into his story without a title sequence, his main character introducing herself through voiceover narration. The casting of Gena Rowlands–leading lady and wife of actor/ filmmaker John Cassavetes–as the teacher allows Allen to paint with a new brush. Unlike Diane Keaton in the seventies or Mia Farrow in the eighties–playing variations on the same outwardly neurotic and inwardly fragile, or outwardly fragile and inwardly neurotic, woman–Gena Rowlands plays a character Allen seems to aspire to personally. Marion Post is a woman of keen intellect but also incomparable measure, a mentor defined by the fine example she’s setting as opposed to the flaws she might burden others with. Rowlands possesses such well-mannered temerity that we’re invested right away in seeing where the cracks in her character lie and how deep the story will drive a wedge in them.

Replacing his frequent director of photography Carlo Di Palma with Sven Nykvist–for the first of four collaborations–seems to have functioned mostly as a good luck charm for Allen to channel the sort of fluid, dreamlike story quality he hoped to emulate, but whoever can take credit, Another Woman has a sophisticated visual quality beyond the quick sketches Allen’s previous work contained. The cast seems to have helped push the filmmaker into new territory. Ian Holm–rarely cast as husbands, perhaps given his height–gives an innocuous performance that we don’t trust from the get-go, but we have to believe his wife does trust. Gene Hackman is a great choice opposite Gena Rowlands, playing a man of strength and integrity who’d nullify all of that for the woman he loves. Martha Plimpton is under the radar as one of the best teenage actors Allen would ever work with, a 16-year-old who is credible as someone who spends most of her time around adults, while Sandy Dennis (in two scenes) and Betty Buckley (in one) play women unquestionably more bitter than Marion, but also more awake. Even Mia Farrow, appearing initially as a voice and later, a woman who realizes she doesn’t have nearly the problems someone else does, has Allen operating outside his comfort zone. In addition to Marion writing about German philosophy and appraising the poetry of Rainer Rilke, the piano and/ or cello suites of Bach are heard throughout, encasing the soundtrack in a certain stoic wonder.

Woody’s cast (from most to least screen time): Gena Rowlands, Mia Farrow, Ian Holm, Gene Hackman, Martha Plimpton, Blythe Danner, John Houseman, Philip Bosco, Harris Yulin, Betty Buckley, Sandy Dennis, Frances Conroy, Jacques Levy, David Ogden Stiers, Bruce Jay Friedman, Josh Hamilton

Woody’s opening credits music: “Gymnopédie No. 1,” by Erik Satie, performed by Orchestre de la Société des Concerts du Conservatoire (1957)

Woody’s closing credits music: “Symphony No. 4 in G Major,” by Gustav Mahler, performed by The New York Philharmonic conducted by Leonard Bernstein (1960) / “The Bilbao Song,” by Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht, performed by Bernie Leighton (1988)

Video rental category: Drama

Special interest: Midlife Crisis

Hey Joe… Good morning! Hope all is well with you, I so enjoy reading your analysis and background information on all of the movies that you review… But this one really peaked my interest, having never saw it, primarily for out of the comfort zone and norms for Woody Allen And just the cast of characters that I really respect… Thank you for this one, and I’ll be checking it out soon. Peace! CPZ.