After Hours at 40

A night in SoHo goes from bad to worse in wondrous B-movie

In the month of September, Video Days plays the sucker for women who lure us into a world of danger.

AFTER HOURS (1985) is one of the more overlooked comedy/ horror pictures of the last half century, a comedy/ horror for those with a distaste for “horror,” especially when mixed with their comedies. More commonly shelved among the gritty and intense urban films its master director is revered for, the movie excels as a slow-moving nightmare which could only take place in a city like New York. It’s strikingly oddball, with the majority of its cast striking quick comic jabs before disappearing into the night, contributing to the film’s strangeness.

Joseph Minion was born in Teaneck, New Jersey, a bedroom community in the New York metropolitan area. In 1977, a twenty-year-old Minion moved to the city and started making experimental films, which screened at the Collective for Living Cinema in lower Manhattan. He was accepted into film school at New York University, where a professor named Arnold Baskin introduced him to the short films of Roman Polanski. Minion dove into all of the French director’s work, but the one that made the biggest impact was The Tenant (1976), with its blend of alienation, humor and despair. Minion saw the film as the flip side of the Martin Scorsese-directed Taxi Driver (1976), with a man imploding under pressure rather than exploding. This started Minion thinking about how to combine comedy and horror, with claustrophobia playing a major part. He transferred to Columbia University, continued writing and shared his work with Dušan Makavejev, the Serbian filmmaker who was one of his professors. In 1981, Makavejev was invited to the Sundance Film Festival in the inaugural year of its film labs, which paired emerging writers or directors with industry professionals. Accompanying Makavejev as his assistant, Minion packed a copy of this thesis screenplay, titled A Night In SoHo.

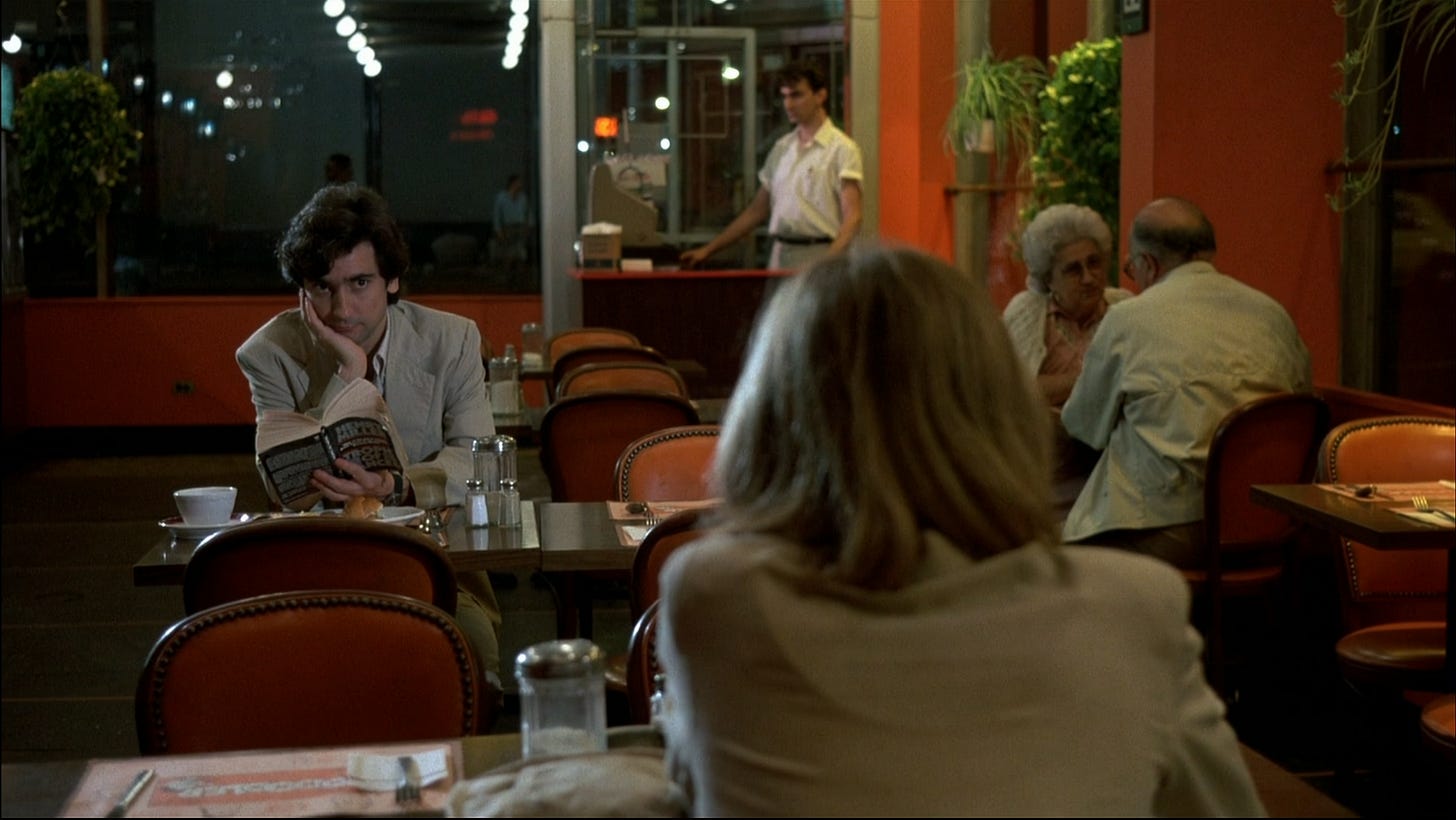

Also in Park City for the festival was producer Amy Robinson, who’d played Theresa in another Scorsese picture, Mean Streets (1973), and in 1978, co-founded Triple Play Productions with a pair of actors from New York named Griffin Dunne and Mark Metcalf. The trio had optioned Anne Beattie’s debut novel Chilly Scenes of Winter and snaring Joan Micklin Silver to adapt a script and direct, got the film produced, though in a concession to their financiers, released as Head Over Heels (1979). Metcalf, who played Douglas Neidermeyer, the main heel in National Lampoon’s Animal House (1978), would drop out of the company to focus on acting, prompting Robinson and Dunne to rebrand their shingle Double Play Productions. When Amy Robinson returned from Sundance, she read A Night In SoHo and shared it with Dunne, who was despondent that what he felt should be his big acting break—in Animal House director John Landis’ An American Werewolf In London (1981)—had him decaying under prosthetic makeup. Dunne loved A Night In SoHo and seized on the opportunity to play Paul Hackett, a word processor who connects with a woman in a diner and impulsively travels downtown at night to see her, ending up in places he has no business being. Double Play optioned the script.

Joseph Minion had been influenced by the Franz Kafka novel The Trial and its Orson Welles-directed film adaptation in 1962, which starred Anthony Perkins as Josef K., a bank clerk hounded for a crime no one will disclose to him. A Night In SoHo may have started as a comedy, but the script descended into unease and dread. Robinson and Dunne had gone to a theater to see Tex (1982), to which Walt Disney Pictures attached a striking six-minute black and white stop motion animation film titled Vincent (1982). Robinson and Dunne agreed that its director–someone named Tim Burton–would be ideal to direct their nightmarish comedy. The producers met with Burton at Disney Studios in Burbank and he agreed to direct, later sharing sketches he’d drawn, inspired by the script. Teri Garr was subletting Dunne her New York apartment while she was out of town working, and to give their project some prestige, Dunne offered her the role of the beehive-hairdo barmaid, Julie. With Double Play’s second production–Baby It’s You (1983), an original screenplay by Amy Robinson rewritten and directed by John Sayles–headed for release in the spring, Robinson and Dunne secured a bank loan of $3.5 million. It was contingent on A Night In SoHo landing a distributor.

Having never directed a live-action film, Tim Burton’s name was hindering rather than helping the search for a distributor. Robinson knew her attorney Jay Julian also represented Martin Scorsese, and she also knew that the director was available, Paramount Pictures having pulled financing from The Last Temptation of Christ in late November 1983. Robinson asked Julian to pass Scorsese their script. The director of Mean Streets and Taxi Driver had not only endured his passion project being cancelled weeks before the start of shooting, but his last three narrative pictures–New York, New York (1977), Raging Bull (1980), The King of Comedy (1983)--had been ignored by audiences. Scorsese was wondering whether this was the end of his directing career. Coming out of the dark, A Night In SoHo read like a novel to him: fresh, full of gusto and kooky dialogue. He didn’t know where it was headed. Scorsese identified with Paul Hackett, who like the director, had been booted into a purgatory he felt trapped in. Rather than let the film industry think he was giving up, Scorsese saw an opportunity to get back to work by going back to his roots.

When Robinson and Dunne broke the news to Tim Burton that they had a chance to make A Night In SoHo with Mr. Scorsese directing, Burton graciously withdrew from consideration. Scorsese’s main influences were a pair of slapstick comedies directed by Allan Dwan, Up In Mabel’s Room (1944) and Getting Gertie’s Garter (1945), lightning-paced B-movies with capable if not star-studded casts. Within ten years, Scorsese’s cast would look pretty spectacular. He never suggested anyone but Griffin Dunne play Hackett. As Marcy, the beguiling blonde who lures him into a world of danger, Scorsese wanted to work with Rosanna Arquette, from Baby It’s You. Linda Fiorentino aced her audition as Kiki Bridges, Marcy’s roommate, a sculptor. Teri Garr was available to play Julie, while Robinson and Dunne went to bat for John Heard, their leading man from Chilly Scenes of Winter, who had something of a wild reputation, to play a bartender. Scorsese recruited Verna Bloom, who he’d cast as Mary, Mother of Jesus, in The Last Temptation of Christ, and Catherine O’Hara, who Scorsese had wanted to work with since seeing her perform on SCTV. Searching for someone like Cheech & Chong to play the thieves Neil and Pepe, it was suggested to Scorsese they could simply cast Cheech Marin and Tommy Chong (credited as “Thomas Chong” for what he must have considered a respectable acting gig). Will Patton—last seen menacing Rosanna Arquette in SoHo for Desperately Seeking Susan (1985)—and Bronson Pinchot made appearances.

With Martin Scorsese directing, the Geffen Film Company came aboard as distributor, David Geffen, founder of Asylum Records and Geffen Records entrusted by Warner Bros. Pictures to develop film material under a certain budget for the studio to fill its release slate with. Geffen agreed to kick in $500,000 to Double Play’s $3.5 million bank loan. For a director of photography, Robinson and Dunne suggested the cinematographer of Baby It’s You, Michael Ballhaus, who working in Germany had by necessity learned to shoot on a tight schedule. Ballhaus would light six more films for Scorsese, from The Color of Money (1986) to The Departed (2006). Shooting what was now titled After Hours commenced in July 1984. Scorsese, who’d grown up in lower Manhattan in the neighborhood of Little Italy, didn’t have the luxury of making the geography of his film accurate, but got close. Most of the scenes set in SoHo–Kiki’s loft apartment, Spring Street subway station, the “Terminal Bar” (shot in the Emerald Pub) and Julie’s apartment–were filmed after hours in SoHo, which had yet to be gentrified by residents prickly about film crews near their properties, especially at night. The eatery Paul takes Marcy to was the River Diner, a classic chrome diner located in Hell’s Kitchen.

After Hours opened in limited release on September 13, 1985, in one theater in New York. Newspaper critics leaned positive. On their syndicated TV program, Gene Siskel & Roger Ebert gave the film two thumbs up. Siskel enjoyed it, but qualified his recommendation by stating that the appearance of light comedy actors (Garr, O’Hara, Cheech & Chong) robbed the film of its New York edge toward the end. Ebert categorized After Hours as a comedy that made him feel a great deal of tension even while he was laughing. He read After Hours as a textbook in how a director can manipulate an audience. Ebert would propel it to #2 on his list of the year’s ten best films. Writing for the New York Times, Vincent Canby delivered a mixed notice, praising the photography by Michael Ballhaus and direction by Scorsese as taking "on an aggressive, willful personality of its own." He compared After Hours unfavorably to Taxi Driver, Raging Bull and The King of Comedy, concluding it "is not, ultimately, a satisfying film, but it's often vigorously unsettling. In this season of homogenized pap, that should be read as praise.” Warner Bros. expanded After Hours to a meager 503 theaters for its sixth weekend in release. It barely cracked the top ten for three weekends before disappearing, but Scorsese had rediscovered his passion for filmmaking, kept working and within five years would be considered by some the greatest living American film director.

A year after Robinson and Dunne optioned Minion’s script in 1982, writer Joe Frank performed an 11-minute monologue on NPR Playhouse titled Lies which bore an uncanny resemblance to what would become the first thirty minutes of After Hours. Frank’s unnamed narrator meets a woman at a deli and after some conversation, she offers him paperweights shaped like bagels and cream cheese that her roommate is selling. The man phones her that night and though she lives downtown, he goes to see her. A gust of wind blows his only cash (five dollars) out the window of his cab, leaving him without fare home. Retiring to her bedroom, the woman shares a story about a rapist who came in through the fire escape, an ex-boyfriend whose assault she mostly slept through. She later reveals she has a husband (in Romania) she left for his odd behavior (defecating in bed) but whom she writes to every day. With striking similarities as well as odd differences–the woman in Lies is named Mary instead of Marcy–this material ended up in a 4th draft of After Hours dated 6/6/1984 credited to Joseph Minion for Double Play Productions. This means that either Minion ripped off Joe Frank’s radio broadcast for rewrites of his script, or more likely, that Frank read or heard about Minion’s unproduced screenplay and stole some of its first 35 pages before the movie could be produced. No one involved in After Hours has credited Lies as a source, and no lawsuits were filed.

After Hours is a film Martin Scorsese could only have directed in the year of his career that he did, and that may be reason alone to cherish rather than overlook it. The picture finds its level among Yuppie horror movies like Risky Business (1983) and Lost In America (1985) — all produced by the Geffen Film Company–which poked at urban professionals, implying that their bright futures were one moment of weakness from being blown to bits. The instrument of destruction in After Hours is Rosanna Arquette, who gives a brilliantly off-center performance as a woman manufacturing such decent character she even believes she means well. Joseph Minion’s script creates situations that while improbable under the glare of daylight–like Hackett not carrying an ATM card–feel possible by night, such as the most generous bartender in New York keeping his money in a cash register that won’t open. The implication that the gods are screwing with Hackett builds until the only release is to laugh at his predicament. For Scorsese’s bustling camerawork (the cab ride from hell–or to hell–belongs on any reel of his most visceral sequences), Griffin Dunne achieves a mellow rather than frantic energy just right for a guy up all night. With the exception of Teri Garr, playing the same emotionally fraught dingbat she’d played before, the cast is full of surprises, highlighted by Linda Fiorentino as an uninhibited sculptor dangling before Hackett the possibility she might like him. Rather than get wound up, Hackett is wound down, and like him, by the end of the picture we just want to crawl into our bed and catch some sleep.

Video rental category: Comedy

Special interest: 24-Hour Time Frame