8 Million Ways To Die

Lawrence Block's literary sleuth wasted on viewers in cursed thriller

Video Days orders readers to surrender their badge and gun and while suspended for the month of May, return to ten films trafficking in law and order.

8 MILLION WAYS TO DIE (1986) is a textbook case of what a movie that’s been taken away from a director and editor and assembled willy-nilly looks like. It’s a tire fire, as murky and unpleasant as an industrial accident. To make sense of this crime thriller would’ve required the skills of a world class film editor, like Hal Ashby, who won an Academy Award cutting In The Heat of the Night (1967), and as a director, guided ten actors to Oscar nominations in the 1970s. In what would be his final film, Ashby was dismissed as director shortly after wrapping 8 Million Ways To Die, a mindless misuse of authority that viewers end up being punished for.

Lawrence Block was born and raised in Buffalo, New York. In 1956, he enrolled at Antioch College, a private liberal arts school in Ohio, but dropped out after one year. Block moved to New York City and spent even less time–nine months–working as a reader for the Scott Meredith Literary Agency. As early as high school, he’d learned to write to the market, and looking to become a professional writer in New York, proceeded to read every back issue of Manhunt, a postwar literary noir magazine, to dial in exactly what their editors wanted. In February 1958, Manhunt published him–the short story ”You Can’t Lose”–and Block quit his job to write full-time. His first novel, written as Grifter’s Game, was published in 1961 under the title Mona. It was about a con artist named Joe Marlin who comes by a suitcase full of heroin and partners with the wife of the man looking for the dope to kill him. Many novels and short stories followed before 1976, when Block introduced the character of amateur detective Matthew Scudder in The Sins of the Fathers.

Scudder was an alcoholic ex-NYPD detective living in Hell’s Kitchen, scraping by doing favors for friends—or friends of friends—in trouble, at least when he isn’t hung over. The fifth novel in the series–published in 1982 and titled 8 Million Ways To Die–saw Scudder accepting he had a drinking problem and joining Alcoholics Anonymous. Oliver Stone, the Academy Award winning screenwriter of Midnight Express (1978) clawing his way toward a career as a director, partnered with Steve Roth, formerly of Creative Artists Agency who’d resigned in 1982 to become an independent producer, to option the film rights to Matthew Scudder. Stone’s adaptation of 8 Million Ways To Die welded it with the fourth book in Block’s series, A Stab In the Dark. Stone, who’d written Conan the Barbarian (1982), Scarface (1983) and The Year of the Dragon (1985) on commission, saw Lawrence Block’s sleuth as an agent he could use to explore the impact of the drug trade on the lower class of the Alphabet City neighborhood in New York.

Oliver Stone hoped to direct, and though Roth lined up distribution with Embassy Pictures, the producer struggled to secure financing. Stone did finally meet an angel financier in John Daly of Hemdale Film Corporation, but Daly was interested in two other scripts Stone had authored: Salvador, about journalist Richard Boyle’s plunge into revolution in Central America, and Platoon, an account of Stone’s experiences serving on an infantry unit in South Vietnam. Choosing to direct Salvador (1986) first, before the conflict disappeared from the news, Stone left 8 Million Ways To Die in the care of Steve Roth. The producer was able to line up financing with an outfit called Producers Sales Organization (PSO), a film finance and distribution company co-founded by actor Mark Damon in 1977 to sell American films abroad. By 1985, Damon (no relation to actor Matt Damon) had stepped down as chairman to run worldwide production and distribution, and John W. Hyde had assumed the role of chief operating officer. For 8 Million Ways To Die, Damon and Hyde (functioning as executive producers) envisioned Walter Hill and Nick Nolte of 48 HRS. (1982) reuniting to direct and star.

Hill’s unavailability opened the door for Hal Ashby to campaign for the job. Every picture the editor-turned-director had put in his spinning wheel in the 1970s had converted straw to gold: Harold and Maude (1971), The Last Detail (1973), Shampoo (1975), Bound For Glory (1976), Coming Home (1978), Being There (1979). Like several of his peers, Ashby’s magic had faded in the 1980s, with Second-Hand Hearts (1980), Lookin’ To Get Out (1982) and The Slugger’s Wife (1985) all critical and commercial disappointments. Ashby saw the potential in 8 Million Ways To Die to turn that around, but neither he nor his production designer Michael Haller were familiar with New York. They promised PSO they could make 8 Million Ways To Die cheaper if retooled for Los Angeles. With Oliver Stone unavailable for rewrites, Ashby attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings and began polishing the script on his own, sharing fifty or so pages with Steve Roth. Jeff Bridges and Rosanna Arquette (replacing Jamie Lee Curtis, who’d departed the project over salary) wanted to work with Ashby and committed to play the leads, joined by a newcomer named Andy Garcia, cast as a Colombian drug dealer.

Operating with a sense of urgency to get 8 Million Ways To Die into theaters before May 1986–when Short Circuit, Top Gun, Cobra and Poltergeist II: The Other Side were scheduled for release–PSO hired their own writer to adapt Stone’s adaptation. R. Lance Hill was a novelist operating in Hollywood under the pseudonym “David Lee Henry.” Hill took notes from the financiers without being permitted to collaborate with or meet Hal Ashby and Steve Roth. Unhappy when they found out their financiers were rewriting their film, Ashby and Roth were joined by most of their cast in their dislike for Hill’s script. To perform emergency triage, PSO turned to script doctor Robert Towne, who’d worked with Ashby as the screenwriter of The Last Detail and (with Warren Beatty) Shampoo. Towne, notorious for the deliberate pace he worked when writing for himself, managed to complete half the script for 8 Million Ways To Die before shooting got underway in July 1985 in Los Angeles.

Towne’s focus was less on the pulp aspects of Block’s novels than it was the struggles of an ex-sheriff’s deputy to get sober. Alcoholics Anonymous, which had withheld their trademarked name and procedures from use in film or television, admired Towne’s script so much they made an exception for 8 Million Ways To Die. Ashby, Towne and Roth no longer felt they were adapting a Lawrence Block novel or novels, and considered retitling their picture Easy Does It, an AA slogan. Working without a completed script, Ashby huddled with Bridges or Arquette in their trailers between setups, dialing in scenes they had to shoot the next day. Towne did complete an entire script in an expedient six weeks, by mid-August, but Ashby continued to improvise with his cast, who were confident that the director and his editor Robert Lawrence would assemble a provocative psychological thriller in post-production. Their version of 8 Million Ways To Die introduced Scudder taking part in an officer-involved shooting of a man in front of his wife and children. To self-medicate, he starts hitting the bottle, derailing his career in the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department, as well as his marriage.

Scudder ends up in Alcoholics Anonymous, where a woman seeks his help on behalf of a friend in trouble. She gets Scudder into an underground gambling den that’s perched on a hill, accessible by funicular. He’s familiar with the club owner, Chance Walker (Randy Brooks) and is introduced to the woman in peril, a sporting lady named Sunny (Alexandra Paul), as well as a flashy drug smuggler named Angel Maldonado (Andy Garcia) who’s infatuated with a blonde working the club named Sarah (Rosanna Arquette). Scudder leaves the joint with Sunny and she asks for his help quitting the prostitution ring she’s caught up in, offering Scudder $5,000. He meets with Chance to offer him half his fee, but the club owner insists he’s no pimp and has no hold on what the girls in his club do outside it. Before Scudder gets any answers, Sunny is abducted in front of him and killed, her body thrown from a bridge. Scudder goes on a bender and after he regains his faculties, sets out to find the killer (the WGA would award screenplay credit to Oliver Stone and David Lee Henry, based on a novel by Lawrence Block).

Stone–who visited the set in Malibu, where a hilltop mansion on Cross Creek Road that once belonged to record producer David Foster, with operational funicular, was used for the club exteriors–would, based on his recent experience shooting Salvador for less than $4.5 million in Mexico, consider what he saw on Ashby’s set extravagant (the publicized budget for 8 Million Ways To Die would be $18 million). Lawrence Block noted that Ashby would encourage his actors to get into a scene by playing an over-the-top version, which Ashby would dial down in subsequent takes. After 86 days of shooting, he wrapped production and turned his assembly over to his editor, with Robert Lawrence promising he’d have a cut they could begin working on by Christmas. Using Ashby’s absence to cite unprofessionalism, PSO dismissed the director and brought in Stuart Pappé, who’d edited several comedies for director Paul Mazursky, to cut their picture. Several of the off-the-cuff takes Ashby had pushed his actors through and likely not intended for anyone to see ended up in the finished film.

Distributed by TriStar Pictures, PSO’s cut of 8 Million Ways To Die opened in late April 1986. It was an unmitigated critical and commercial disaster. Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert turned two thumbs down. Siskel called the film “flash and trash” and cited the excessive levels of machismo between the characters played by Bridges and Garcia. Ebert faulted the film for attempting to marry a recovery story with a picture that glamorized the drug trade. TriStar opened it in only 215 theaters, where the picture failed to crack the top ten at the box office, an embarrassment considering its prestige at writing, directing and acting. The following month, a piece by Michael Dare for L.A. Weekly charted the disaster, with Bridges, Arquette, Ashby and Roth commenting and candidly sharing their disappointment, and Mark Damon attempting to salvage his company’s reputation. PSO would be forced into Chapter 11 bankruptcy by its creditors in August, while Ashby, in declining health, never directed a feature film again (diagnosed with pancreatic cancer in 1988, he died shortly thereafter at the age of 59).

Lawrence Block is considered by many to be creator of the best private detective fiction ever published. None of that is evident in the film version of 8 Million Ways To Die, which validates every criticism haters tend to harbor toward Hollywood. Those involved–filmmaking and financing–take two bestselling novels, one a serviceable mystery, the other loitering into the literary with a private detective on the wagon, and fiddle with them until what remains is related to a book or series of books in name only. In retrospect, hiring Hal Ashby to direct was a debacle. For starters, the studio didn’t want him. There were any number of directors capable of making a visually compelling mystery set in New York. If shooting in the tri-state area was cost prohibitive, there was a way to credibly relocate Matthew Scudder to Los Angeles, and that was by pretending the movie was set in Los Angeles. By 1985, Scudder would’ve been mired in L.A.’s sprawling gang culture, and a screenwriter of Oliver Stone’s caliber would’ve been able to mirror the cycle of alcoholism in Scudder’s life with the cycle of violence on the streets. Rather than get the script right, the studio appears to have sacrificed quality to get one screenwriter cheap and fast, and surrendered a considerable sum of money for a script that was of marginally higher quality and fast.

8 Million Ways To Die gets off to a creaky start with Jeff Bridges playing an alcoholic who rather than hurt anyone or himself on the job, is just a mess. Based on the editing, it’s hard to tell what’s going on or why we should care. Even if the film had included pedestrian scenes of Scudder losing his job or alienating his family (the actors playing Scudder’s wife and daughter are reduced to awkward cameos), the clarity wouldn’t have improved the movie. This entire prologue could’ve been shorn. More opportunities are wasted. Alcoholics Anonymous is a rich environment for people with troubled pasts to seek the help of an ex-cop, but the picture lacks a compelling mystery, or even a coherent one. Whatever it is that the characters played by Bridges and Rosanna Arquette are doing when they meet is unclear. When Scudder is on a bender, Bridges demonstrates what a gifted physical actor he is, but the film backs away from getting the viewer up close and personal with Scudder’s disease. The bright spot is Andy Garcia, then an unknown actor, free-styling and exuding charm as the heavy. The editing is such a clusterfuck that it’s unclear why any of these characters are associating with each other. When in the same scene, Bridges and Garcia are clearly making most of their macho dialogue up, while Arquette’s character goes from despising Scudder one moment to agreeing to help him the next. Sifting through the dumpster fire for clues, there doesn’t appear to have been a structure, but plenty of oily rags and matches.

Video rental category: Mystery/ Suspense

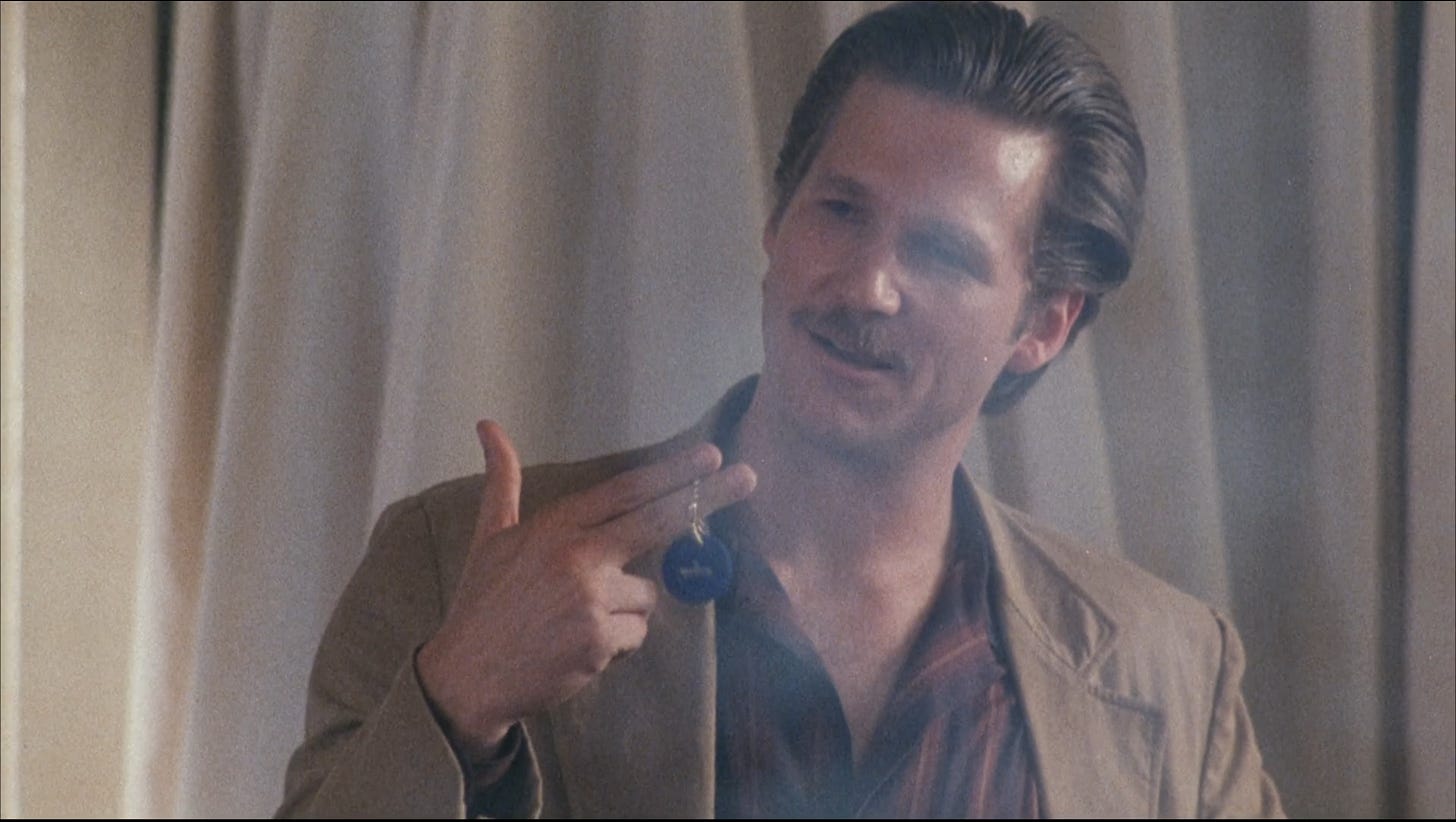

Special interest: Sobriety Chip

Hey Joe, good morning! I already love your analysis and humor more than the movie, that I’ve never seen… And of course now, I’m not moved to ever see it… Great job, as always, very entertaining… Peace! CPZ